Photo: www.rickautosportpictures.com

Today marks 24 years since the sad death of Alfonso de Vinuesa, a driver who could have been Spain’s next Formula 1 star before a life-changing injury. Ida Wood searches for memories of the man, and some answers

I first heard of Alfonso Garcia de Vinuesa in 2020, and he was a driver whose career was an immediate source of fascination. Firstly it was the variety of cars he drove, a truly brilliant mix and with great liveries too, but the more research I did the more I realised his story resonated on a personal level, although sadly for him life was surrounded by and ended in tragedy.

De Vinuesa was born in Madrid in 1958, became a tinkerer from a young age and was firmly in the belief by the time he reached his 20s that he could one day be a Formula 1 driver. He had other commitments in life, such as education, but the only school he was interested in was the one of racing.

And as it had it, de Vinuesa was a student in the first ever course of Emilio de Villota’s eponymous racing school in December 1980. This experimental endevaour, for both parties, was centred around testing the Image FF5 car raced in Formula Ford 1600 in the UK.

FF1600 immediately attracted de Vinuesa’s attention, but there was no Spanish championship and so he spoke to Image’s sales manager (and FF1600 racer) Robert Synge about driving for the manufacturer in England. He didn’t have the money, but then the next year de Vinuesa contacted Arturo Marcos, co-founder of de Villota’s racing school, with a plan.

“At the beginning of the summer of 1981, Alfonso came to me and said ‘listen Arturo, I have a little bit of money and I want to do at least a couple of races’,” Marcos recalled to Formula Scout.

“So I went investigating teams in England, and I phoned Clive Wood of Pine City Racing.”

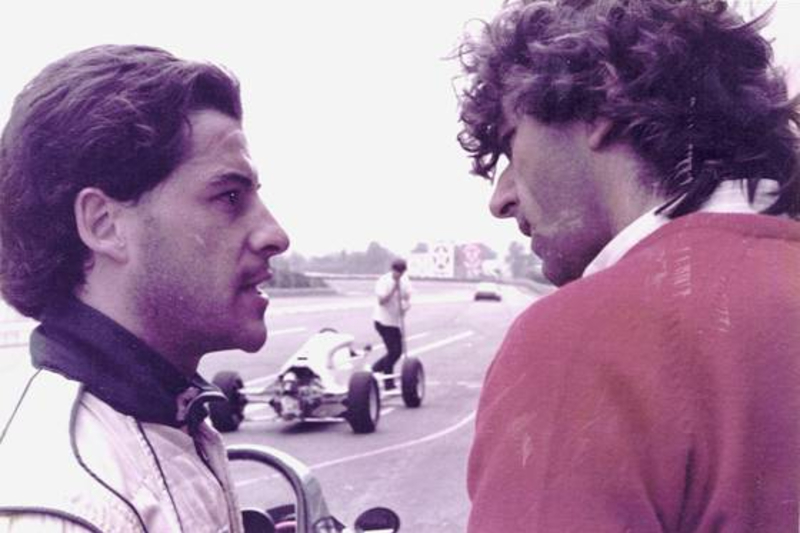

de Vinuesa and Dennis Rushen

With sponsorship from White Label whisky, the cost-concious de Vinuesa struck a two-race deal in a Van Diemen RF81.

“I don’t think they were major championships, because a major championship would mean more testing and more expensive,” Marcos adds. “But what is for sure if that it didn’t matter in which race he ran, he always took it very, very seriously. He had a very professional mentality and approach, and in 1982 we were rivals.”

The next year, de Vinuesa had his first car racing campaign in Spain’s entry-level Formula Fiesta series, which used Van Diemen chassis and 1.3 and 1.1-litre engines built in Ford’s relatively new Valencia factory. He came second in the points to Antonio Albacete, who was being run by Marcos, after a season-long neck-and-neck title battle decided in the final race.

“In the summer we all coincided, because in the summer there is no racing in Spain,” Marcos explains. “So Antonio and Alfonso went to England with different teams, they did some FFord races there. We were running a RF82 with Madgwick Motorsport (founded by Synge), as by then Image had disappeared. Alfonso continued with Pine City Racing with the RF81.”

Soon de Vinuesa was on Madgwick’s books too, as he joined the team for British FF2000 in 1983, but the combination didn’t last and he left the team not on the best of terms. Marcos remembers the next move as being to Rushen Green Racing.

Intensely focused on his racing goal, but also stubbornly cost-aware, de Vinuesa mostly ‘did his own thing’ from 1983 onwards. After bringing Marcos in for assistance to make his racing debut, he’d made clear after that the more people who were involved in his racing efforts, the more money he’d have to spend (and therefore find) to reward their assistance.

He spent a second year in F2000, but went continental and joined Madgwick again, and also entered the FIA European Formula 3 season finale at Jarama in October with Eddie Jordan Racing. Driving an older Toyota-powered Ralt RT3, de Vinuesa qualified an incredible third place and 0.17 seconds off pole on his debut but then crashed out on the opening lap.

For 1985 and ’86 he competed part-time in German F3, picking up one win at the Wunstorf airport track and coming seventh in the standings. De Vinuesa had difficulties finding sponsorship to race full-time, so spent sparcely but what he thought was wisely, and ended 1986 with a deal to contest the International Formula 3000 finale at Jarama. Could 1984 repeat itself?

For 1985 and ’86 he competed part-time in German F3, picking up one win at the Wunstorf airport track and coming seventh in the standings. De Vinuesa had difficulties finding sponsorship to race full-time, so spent sparcely but what he thought was wisely, and ended 1986 with a deal to contest the International Formula 3000 finale at Jarama. Could 1984 repeat itself?

This time he qualified 18th, in a car that had failed to even qualify a few times in the hands of countryman Adrian Campos, then avoided trouble and was on for his team’s best result of the year before an accident put him out on lap 43 of 58.

Luis Perez-Sala was also representing Spain in the series, winning that year’s Mediterranean Grand Prix and Birmingham Superprix, and the media latched onto the pair as having a rivalry when both returned for the 1987 season under the same manager, and both driving factory Lola T87/50s, but at different teams. Perez-Sala was a works Lola driver, while de Vinuesa joined BS Automotive.

Alfredo Filippone, a journalist who followed their careers closely, explained to Formula Scout why some saw a rivalry.

“They were of course the top rising stars of Spain,” said Filippone. “Very different one from the other. There wasn’t that level of rivalry, it was more in the press. There was no animosity between them. Knowing that the two were very different as personalities. As much Luis is quite a cool guy, Vinuesa always gave the impression of a very intense person.

“Completely and exclusively focused on racing. Very calm, but not laidback. He was always very focused, very determined. A little bit like Ayrton Senna, who was like that in a sense. Senna had more of an ego though.”

From a journalist’s perspective, what was de Vinuesa like to work with?

“It was not difficult to talk to him, but it was difficult that he would open up to people,” revealed Filippone. “So it was a strange personality. But precisely because of the personality I think everybody was convinced that we would sooner or later get to F1.

Photo: www.rickautosportpictures.com

“You see these kind of people that are really mono-focused, and ready to make any sacrifice for reaching their goal. Certainly he didn’t come from a wealthy background like Luis. He would send some notice that he was keeping every penny for racing.”

To warm up for a proper step up to F3000, de Vinuesa did contest a few races of the inaugural F3 Sudamericana season though. It seemed to do the trick, as he then begun his F3000 campaign with sixth at Silverstone while Perez-Sala crashed.

The pair shared the second row of the grid in round two at Vallelunga, but their podium battle was ended by an engine failure for de Vinuesa. They got even closer next in the next race at a wet Spa-Francorchamps, but it was too close.

De Vinuesa qualified sixth, with Perez-Sala down in 20th, but a drying track and subsequent switch to slick tyres meant they ended up battling for position. On lap 17 the pair went side-by-side into Raidillon, locked wheels and were both thrown into the barriers at Eau Rouge. While Perez-Sala was uninjured, de Vinuesa was unconcious and trapped in his car.

He was thankfully saved from the wreckage, and transferred to hospital with concussion. Cognitive neurosciene has improved significantly in the 34 years since (this writer can attest to that), but there simply wasn’t the means at the time to measure the true extent of the injuries inflicted to de Vinuesa’s head as it decelerated from racing speeds to a standstill in a second.

“After the accident he was… he looked like something had happened,” Filippone recalled. “And I suspect also he didn’t get the right treatment, nobody realised the extent of the damage. And he probably was the first one not to, he was probably the first one to misjudge the effect of the damage.

“So he tried to minimise because he didn’t want to lose the momentum, he didn’t want to lose time. He came back after three races, which was [crazy].”

Less than three months after the crash, de Vinuesa was back with BS Automotive in F3000 at Brands Hatch, still utterly committed to his racing dream. However, the positive momentum that had been starting to build fell apart.

Less than three months after the crash, de Vinuesa was back with BS Automotive in F3000 at Brands Hatch, still utterly committed to his racing dream. However, the positive momentum that had been starting to build fell apart.

In an oversubscribed grid, de Vinuesa failed to be among the fastest 26 drivers who would qualify to race, and the same happened in Birmingham. The comeback was put on pause, but de Vinuesa didn’t think his form had been affected by the crash and he actually co-ordinated with Marcos for old rival (and new Spanish FFord champion) Albacete to debut with GA Motorsport, which used the same Lola chassis, in the Jarama season finale. If Albacete could make it into the midfield on pace on his debut, then de Vinuesa would have a clue if it was his own driving that was letting him down.

But Albacete failed to qualify, and so de Vinuesa went searching for budget to return for the 1988 season convinced he still had the ability to be as competitive as before his crash. While science couldn’t neccessarily aid his cognitive health, love could in a different way and the 28-year-old’s partner is said to have been crucial in his rehabilitation and racing return.

Domestic peace was going alongside further racing turmoil, though. He started ’88 with Onyx Racing, but quit the team after three rounds and three consecutive DNQs. He didn’t find his way back onto the grid until the second half of the season, joining Tamchester Racing to drive its Reynard 88D. Again, things didn’t work out.

At Brands Hatch he didn’t qualify, and while he did in Birmingham it was of no great value as any hope of a strong result was ruined by having a crashed Russel Spence block his way early on, and then having to sit and watch the Briton (in his car) be craned up and down while the leading pack came to lap him.

He then retired from the race anyway, and after failing to qualify at Le Mans he left Tamchester too. Marcos picks up the story from that point.

“By the end of the year he came to me, and because he knew I had a close relationship with Magwick Motorsport, and their [Reynard 88D] car seemed to be working, and because he did not talk to Robert Synge, he came to me. He said: ‘Listen, you know I’m not on good terms with Robert, would you mind to set up an inbetween because I want to know if the problem is the cars I’ve been driving, or it’s me? I know that Magwick cars are working, so I would like to make a deal with them, but obviously I have nothing with Robert, would you mind being an inbetween?’.”

“By the end of the year he came to me, and because he knew I had a close relationship with Magwick Motorsport, and their [Reynard 88D] car seemed to be working, and because he did not talk to Robert Synge, he came to me. He said: ‘Listen, you know I’m not on good terms with Robert, would you mind to set up an inbetween because I want to know if the problem is the cars I’ve been driving, or it’s me? I know that Magwick cars are working, so I would like to make a deal with them, but obviously I have nothing with Robert, would you mind being an inbetween?’.”

Marcos helped his friend, sealing a deal with Madgwick for de Vinuesa to do the final two rounds at Zolder and Dijon.

“I went with them to the Zolder race and things didn’t work out. And it was a funny situation because we were staying in the same hotel, and he didn’t qualify [for the race]. I remember we were staying in the bar, and it was Alfonso, his manager, Robert from Madgwick, and myself. And even racing in his team he was not talking to Robert!

“So in the bar in the hotel, he tells me:

Arturo, tell your friend that the problem is not the car, it’s me.

“Four people there, and the driver and the team owner not talking to each other. And it was like a film because he was telling me what to tell him.

“But that day he was very self-committed, because I always liked Alfonso on a personal level. He was an incredible person. And I could see that when he told me ‘tell your friend the problem is not the car, it’s me’.

“So he had to admit that [to himself], and then his racing career was over. And it was that moment that he had to admit it, and it was really sad for everybody close to him.”

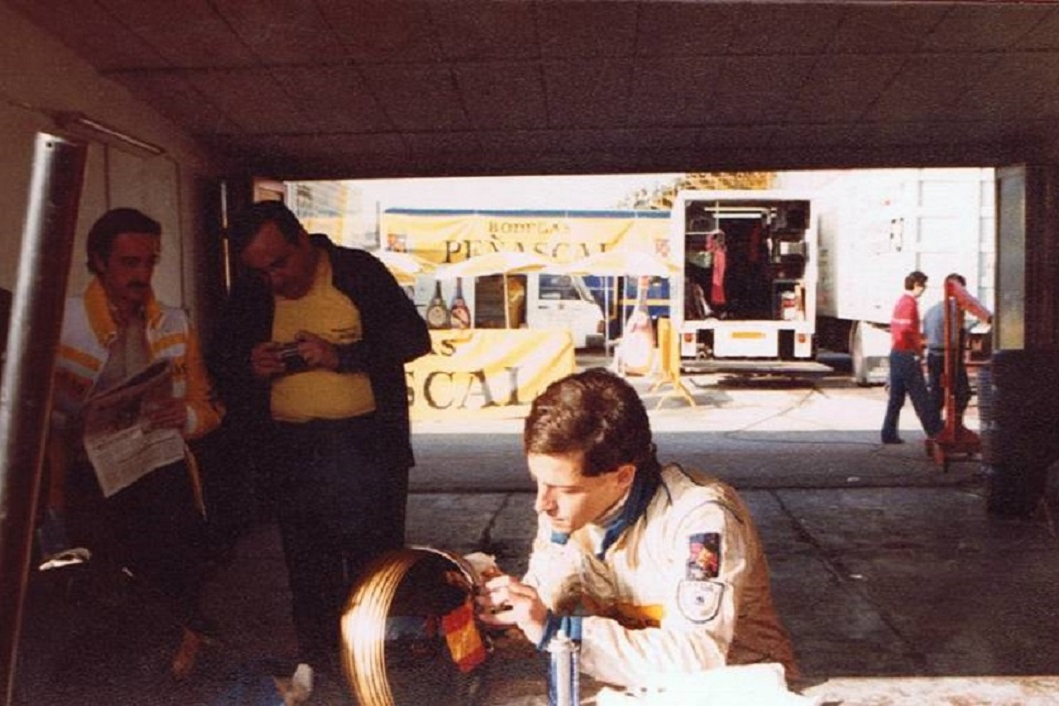

De Vinuesa in his last F3000 race in 1988, Photo: John Clewer

De Vinuesa failed to qualify at Dijon, and that was the last time he sat in a single-seater. That one conversation in the hotel bar, that facing up to a hard truth, was a braver decision than putting his life on the line again in 1989.

“The next time I met Alfonso was when he was running in Spanish Touring Cars in 1991, in a Fiat,” Marcos adds. “And he had found his new girlfriend, and he was happy at the time, but he knew that his days in single-seaters were gone forever.”

After touring cars he ended his motorsport involvement via the Porsche 968 CS Cup, run by the same man who had helped start his career: Emilio de Villota.

But after saying goodbye to his F1 dream, it appeared de Vinuesa entered a depression. And life around him only got worse.

“I remember there was a string of tragedies surrounding him,” says Filippone.

“I know that everything seemed to go wrong for him. And that there were tragedies all around him. I remember that his fiancé got killed in a car accident, and that was really the end of [him] because she had been there [when he got injured], very supportive of him and she was really his last anchor to life.”

The loss of the closest person in his life and his closest passion, racing, came after losing his income when his own business had gone under and losing a member of his family. Many years earlier, his first partner had also died in a skiing accident.

De Vinuesa’s own tragic death on May 24, 1997 came not long after his fiancé’s, occurring as he got out of his car on a busy road to check it for faults, and being struck by a truck. Ruled as accidental, many have suspected it could have been suicide.

Unfortunately de Vinuesa’s story is mainly only known for its ending, but he was a talented driver, well liked by his peers and got to F3000 on merit. With a little more steering from his manager, who got his other two clients Campos and Perez-Sala into F1, it wouldn’t have been a susprise to see a third Spaniard knocking on the door of the sport’s top level too.

D.E.P Alfonso.