Photos: Formula Motorsport Limited

The inclusion of Alessio Deledda in the Monaco Formula 2 races was a contentious issue. Way off the pace in practice and then in qualifying, he fell foul of the 107% rule but still raced. Should F2 regret that choice?

To ensure a minimul standard competitiors, in addition to race licenses and penalty points systems, many motorsport series use a rule that decrees drivers who are not within 107% of the pace cannot compete, so as not to be a safety hazard

It is rare to see the rule used in Formula 1, let alone in the junior categories. It is often nothing more than a footnote for drivers on results sheets and in stewarding documents. Not since 2012 has a driver failed to qualify in F1, when both HRTs were not quick enough at Melbourne, and in the support paddock that last to miss the cut was Carmen Jorda in GP3 in 2012.

Often, there is a very valid reason for a driver being allowed to race if they do fail to make the grade. The most basic of these is if free practice times are quick enough, or if there has been a significant car problem that inflicted their qualifying laps.

It’s something that Mahaveer Raghunathan came close to being on the wrong side of in F2 back in 2019, but he was able to qualify on every occasion, highlighting exactly how much Deledda struggled on Thursday in Monaco.

HWA Racelab driver Deledda’s best lap in the single free practice session was a 1m29.355s, more than seven seconds off the pace set by Prema’s Robert Shwartzman.

He improved by 1.611s in qualifying, but was 6.341s slower than Shwartzman’s Group B-topping lap. That meant he fell foul of the 107% rule by 0.790%. Theo Pourchaire’s stunning pole lap is irrelevant in this equation, as that was set in slightly different track conditions in Group A. In the 29 laps of Monaco that Deledda did on Thursday, not once was he on the pace.

As a result, HWA had to appeal to the stewards to race and were duly allowed to do so from the back of the grid. It’s a move that drew criticism from some corners of motorsport media and especially on social media, somewhat predictably.

The explanation of the stewards’ decision was inexplicably vague:

The explanation of the stewards’ decision was inexplicably vague:

“The stewards summoned and heard the team manager in respect of the request for the start permission for Car 23 [Deledda]. Car 23 is given permission to start race one and race three.

“Competitors are reminded that they have the right to appeal certain decisions of the stewards, in accordance with article 15 of the FIA International Sporting Code and article 10.1.1 of the FIA Judicial and Disciplinary Rules, within the applicable time limits.”

The lack of transparency from the stewards is surprising, but they ultimately made the correct call. When delving into the data, it becomes incredibly clear to see why.

It is worth remembering that Deledda fell foul of a sporting regulation, which are applied less draconianly than technical regulations. Being outside of the 107% rule does not imply being sent home early is guaranteed. It exists for a good reason but should only be used to stop dangerously slow cars from being in a race.

Monaco is a notoriously tricky circuit to learn, and F2 drivers are given just 45 minutes of practice in comparison to the three hours of running that the F1 runners get. F2’s practice was truncated by a number of red flags, cutting down that time too. On top of that, split qualifying further limits the number of laps that can be racked up.

For a circuit where you really have to build up to it, it’s far from ideal. That lack of track time, something teams and drivers have called for more of in recent years, could have played a role in the decision. And Deledda has missed a significant amount of pre- and in-season testing through crashes and car trouble, so his track time deficit in F2 runs further. The little running given to F2’s drivers is what makes its new youngest winner Pourchaire’s achievements all the more impressive, ultimately.

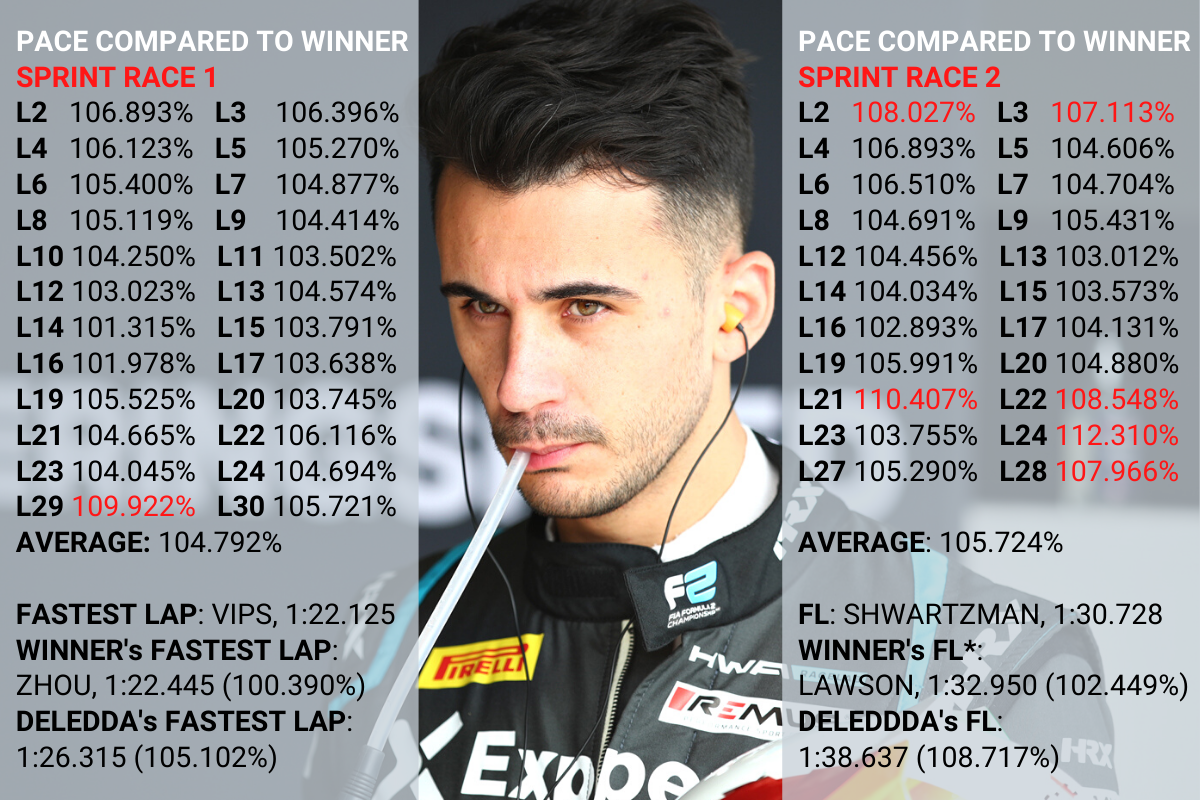

Deledda started from 22nd, 18th and 22nd for the three Monaco races, and to make a reference to his pace (predominantly in clean air as he was gapped by the pack) it can be compared to the driver who crossed the finish line first (and had a similar clear track advantage). That was Virtuosi Racing’s Guanyu Zhou in the first sprint race, Hitech GP’s Liam Lawson (*later excluded for a technical regulation breach) in the second, and ART Grand Prix’s Pourchaire in the feature race.

Deledda started from 22nd, 18th and 22nd for the three Monaco races, and to make a reference to his pace (predominantly in clean air as he was gapped by the pack) it can be compared to the driver who crossed the finish line first (and had a similar clear track advantage). That was Virtuosi Racing’s Guanyu Zhou in the first sprint race, Hitech GP’s Liam Lawson (*later excluded for a technical regulation breach) in the second, and ART Grand Prix’s Pourchaire in the feature race.

The first race is arguably the most relevant, as race two was wet and the feature race featured the mandatory pitstop and more laps where Deledda’s rhythm was broken by having to comply to blue flags (a sign in itself of the pace deficit).

Six of the 30 laps are ignored from the first calculation. Three for the safety car, then the restart, lap one and when Deledda was first lapped. Deledda’s fastest lap was a 1m26.315s, within 107% of what was set in qualifying and 4.694% off Zhou’s best in the race. Of the remaining 24 laps, one was outside of 107% for Zhou’s corresponding lap – the penultimate lap.

Across the race he ran at an average of 4.792% off Zhou’s pace, which is well within the threshold of expected performance.

Sprint race two gives us a slightly smaller sample set of 22 laps, ignoring real and virtual safety cars, being lapped and the start. Despite it being wet, and therefore much more treacherous, Deledda was still within 107% across the race. Six of the 22 laps were outside of 107% of Lawson’s corresponding time. Two at the beginning of the race as he tried to adapt to the slippy conditions, and the other four when he was navigating being lapped by the top six finishers on track.

The 42-lap feature race produced Deledda’s strongest performance. Being on the same soft to supersoft strategy as Pourchaire and pitting a couple of laps within each other allows for a fairly relevant direct comparison.

The seven laps between laps 28 and 34 which featured those pitstops, and three VSCs in quick succession, are ignored, as is the start and being lapped. That gives 33 laps to work with, and again it is just one lap where Deledda’s time was outside of 107% of Pourchaire’s corresponding time. On that occasion, it was the tour immediately after being lapped by the leader.

L25 should be red rather than L26

On average, Deledda was circulating at 103.034% of Pourchaire’s pace, and his fastest lap of 1m24.487s was 102.976% of Pourchaire’s best in the race. After 103 laps of the weekend, his best lap put him 4.324% and 3.502s off the absolute pace.

It was clear that Deledda became much more acclimatised with the streets of the principality as the weekend progressed and was more than within his right to take to the circuit for the races based on his times in them.

To add, he did a fine job of allowing lapped cars by and kept it out of the barriers all weekend; easier said than done on a first visit.

On the contrary, the numbers above are still some way off what a driver at this level should be running at. There was little to suggest in his career to date that Deledda’s move to F2 was justified, and the performances to date have proven it to be the case. From a competition standpoint, he unsurprisingly ran at the back and made zero impression at any point he was on the lead lap.

But, from a point of being allowed to race, Deledda was absolutely within his right to on one of the most famous circuits in the world. And as a result, the stewards nailed that decision. It would just be better if their communication improved so if this scenario occurs again with the Italian it doesn’t take journalists having to ask the F1’s race director how decisions are being made in F2 to find out the ‘real’ reason Deledda was sluggish on Thursday was “mechanical issues with that car”.

More F2 2021 analysis

The numbers telling MP Motorsport it needs to keep Verschoor full-time

What Bahrain told us about who’s fastest in Formula 2

Five things we learned from the 2021 Formula 2 season opener