Photos: Van Amersfoort Racing

A young Dutch driver called Verstappen is taking win after win. But an accident stops a summer clean sweep. Daring, aggressive but blessed with outstanding car control, he’s the talk of the series as the title is won early

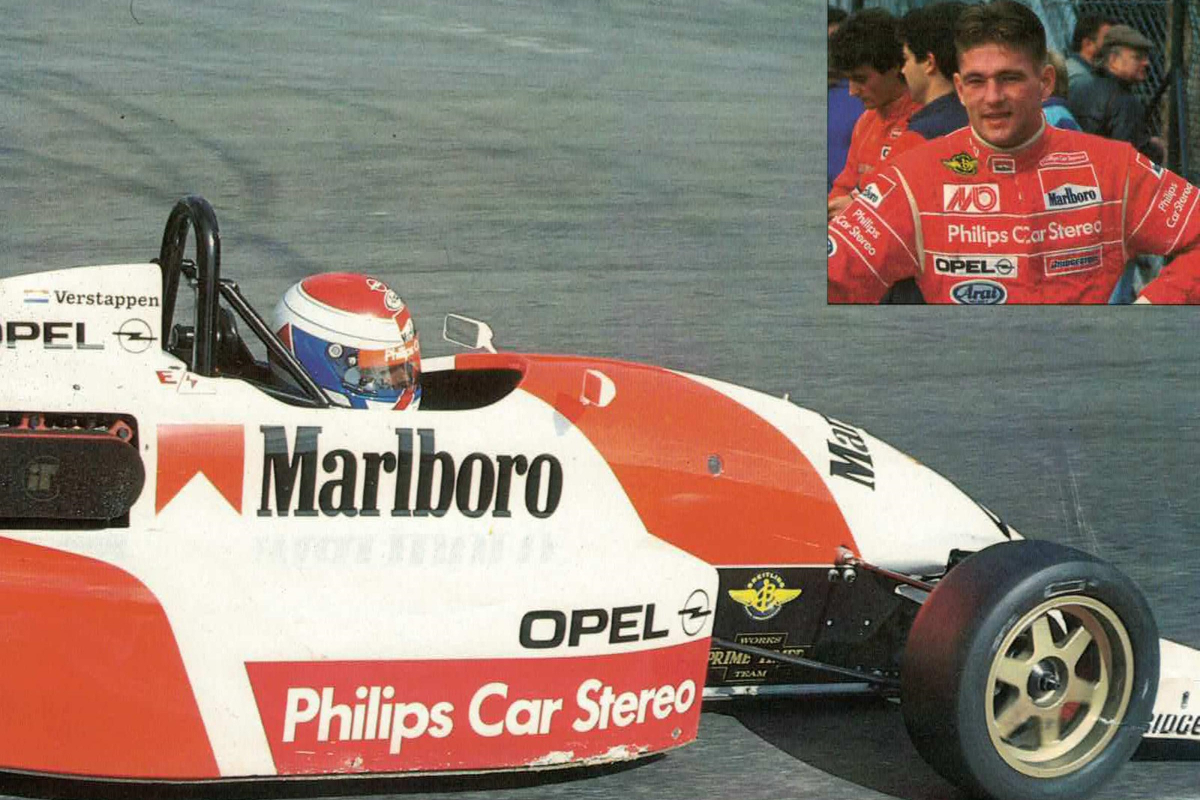

Thirty years ago, Jos Verstappen, now best known as the rather dour father of Max, competed in his first season in cars, winning the Formula Opel Lotus Benelux championship for Van Amersfoort Racing at a canter, before stunning the regulars in the more important and more competitive Euroseries with two crushing victories at Zolder.

One of those who watched Verstappen at close hand, Rob Niessink, then his mechanic at VAR, and now the team’s CEO, says simply that “he just stepped into the car, liked driving fast and he usually won the race”.

Within 12 months, he had wrapped up the German Formula 3 title and stunned observers with his first ever test in a Formula 1 car, a Footwork-Mugen, at Estoril. Glory surely beckoned…

For a variety of reasons, of course, the successes never came. As a driver rather than a parent he is best remembered for almost being incinerated in a flaming Benetton at Hockenheim in 1994. But back in late 1992, Verstappen was being touted as the future of Dutch motorsport and a future Formula 1 world champion.

Verstappen came into car racing on the back of a very successful karting career, winning national titles in the Netherlands and Belgium as well European Super 100 and Intercontinental Formula A honours in 1989.

“Everybody knew about Jos Verstappen in go-karting, that he was something special,” Niessink tells Formula Scout.

“Some years before he actually came to us there was already some sort of contact, but they were afraid they couldn’t afford it and I think he’d also got works contract by then from somebody, from one of the [kart] manufacturers,” he continues.

The contact with VAR came about through former F1 driver and European Formula 2 race-winner Huub Rothengatter.

The contact with VAR came about through former F1 driver and European Formula 2 race-winner Huub Rothengatter.

“Huub was very close to us, he was one of the first drivers Frits [van Amersfoort] helped many, many years ago,” explains Niessink. “He was asked by Frans Verstappen, the father of Jos, in the very early days when Jos was still in karting. Huub went over there to meet them and of course, what Jos did in karts was impressive, he was really successful.”

So Rothengatter arranged with VAR for the then-19-year-old Verstappen to do a test in October 1991.

VAR was racing in Formula Renault 2.0 at the time, but “thought that putting him in the FR2.0 might be a bit too much. We were, in that sense, very green, we thought,:‘Okay, you never know what will happen. A rookie, never been in a car before, let’s play it safe.’”

“We went to Zandvoort, to a track where he’s never been,” remembers Niessink. “We borrowed a very old Crossle Formula Ford car, ages old. In those days you had FFord and pre-1980s FFord, and this was a pre-’80 Crossle.

“I did a lap of the track in my road car, a very old, four-wheel-drive Toyota Tercel, showed him the way and after one lap he said ‘okay, I’ve seen enough’.”

“I then did a benchmark lap for him [in the Crossle] and the car was not completely perfect, let’s say. And it took him really two or three laps or whatever and he really destroyed my laptime. I did some racing in the past and I was an instructor in a racing school and I though this is weird, this is really special.”

VAR has always been a team with its feet firmly on the ground, and didn’t want to get over-excited about unearthing a new talent. “We were always very conservative, so we weren’t sure yet,” Niessink explains, remembering the team also ran other drivers in tests during the winter.

“We’d put them in the car, either in the FR2.0 or in the FOpel and then let them do four or five laps, and then we put Jos in and all the time he was faster, no matter who it was. And then we thought ‘okay, this is really special’.”

“We’d put them in the car, either in the FR2.0 or in the FOpel and then let them do four or five laps, and then we put Jos in and all the time he was faster, no matter who it was. And then we thought ‘okay, this is really special’.”

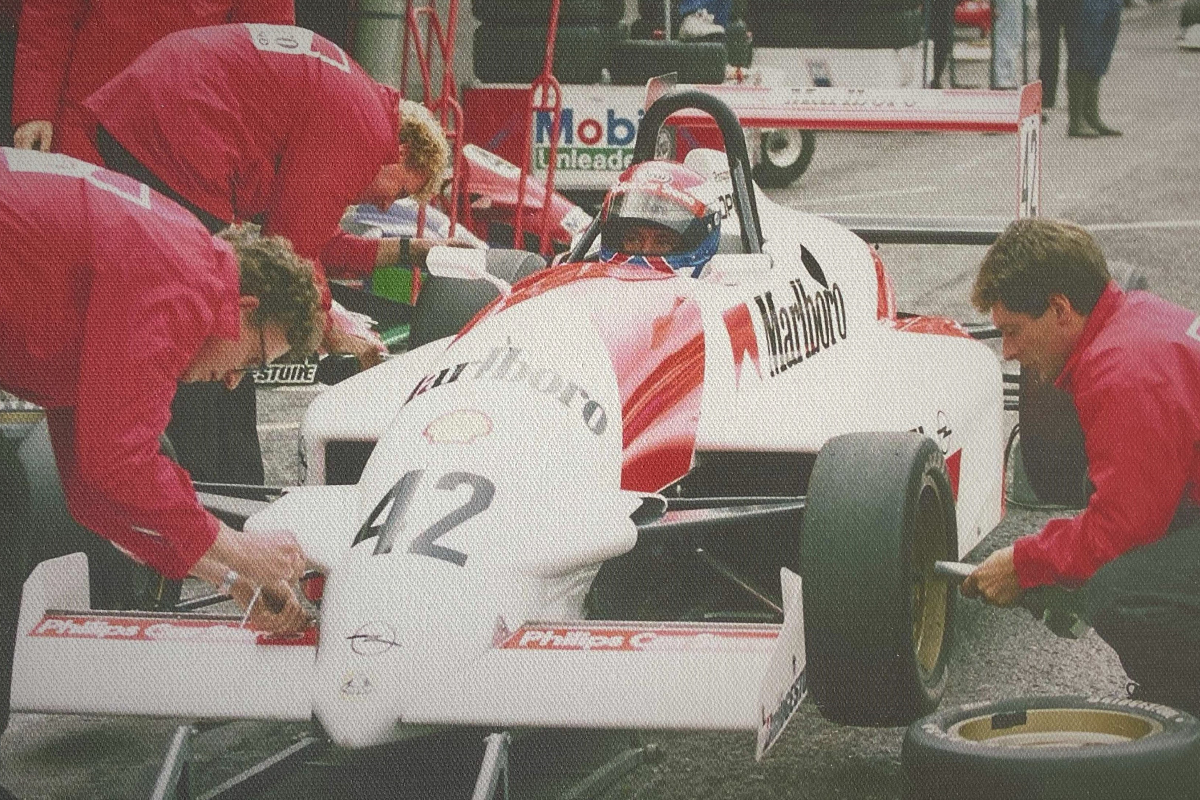

With Rothengatter putting the package together, including sponsorship deals with Marlboro and Philips’ car stereos, the decision was taken to enter FOpel Benelux. Known variously as GM, Opel or Vauxhall Lotus for national marketing reasons, the identical Reynard-built single-seaters were pitched below Formula 3 in the hierarchy of the day, something akin to Formula Regional’ placing in today’s terms.

Verstappen made his debut at Zandvoort over the Easter weekend in 1992, taking a dominant win ahead of 1988 Benelux FFord champion Frank Eglem.

For the celebrating team, however, elation turned to sadness as news reached them of the death of Marcel Albers, another Dutch talent who was 1989 Dutch FFord champion with VAR and a close friend of Niessink, at Thruxton the same afternoon.

Verstappen won next time out at Zolder a week later, again beating Eglem, but when the series returned to the Flemish circuit Verstappen cartwheeled into retirement. It was to be the only Benelux race he didn’t win. Having wrapped up the title with his eighth victory in nine races at Zandvoort in early September, he could afford to skip the final round.

By then, Verstappen had moved onto a wider European stage, and into the view of F1 teams, in the F1-supporting Euroseries. As Niessink recalls, “we decided somewhere halfway, ‘okay, we can do some additional Euroseries races’, and we more or less finished the Euroseries.”

Verstappen twice crashed out and twice finished sixth in his first four Euroseries races, and at his home Zandvoort round he qualified 17th after being caught out by the weather. He then charged through the field to ninth, but not untypically, he paid the price for trying one audacious move too many.

According to Niessink, it was the mark of a young driver unafraid to push to the maximum, and beyond: “Jos has a reputation for being let’s say a crashing driver which is really not too true, but he instantly looked for the limit. Always.

According to Niessink, it was the mark of a young driver unafraid to push to the maximum, and beyond: “Jos has a reputation for being let’s say a crashing driver which is really not too true, but he instantly looked for the limit. Always.

“The very first time he drove at Spa-Francorchamps, in the rain, he was also lightning fast, really seconds faster than anyone else. And people came to us saying ‘who’s driving that car?’. Jos Verstappen. ‘Who?’. Jos Verstappen.”

“It was really remarkable what he did over there. That was in the rain. I think four or six seconds faster than everybody else. Ridiculous numbers.”

As an example of Verstappen’s never-say-die approach to racing, Niessink cites the support race at the Belgian Grand Prix. Approaching the final corner on the last lap he crashed “with another car and he didn’t go off the throttle, went to the other side hitting the wall and still full throttle, he went over the finishing line”.

“And that was Jos, everything was always extreme, but always we went home, and we were often totally flabbergasted, how extremely good he was.”

The mistakes he made were always “at the safe moment of the events, looking for the limit, he did that in free practice”.

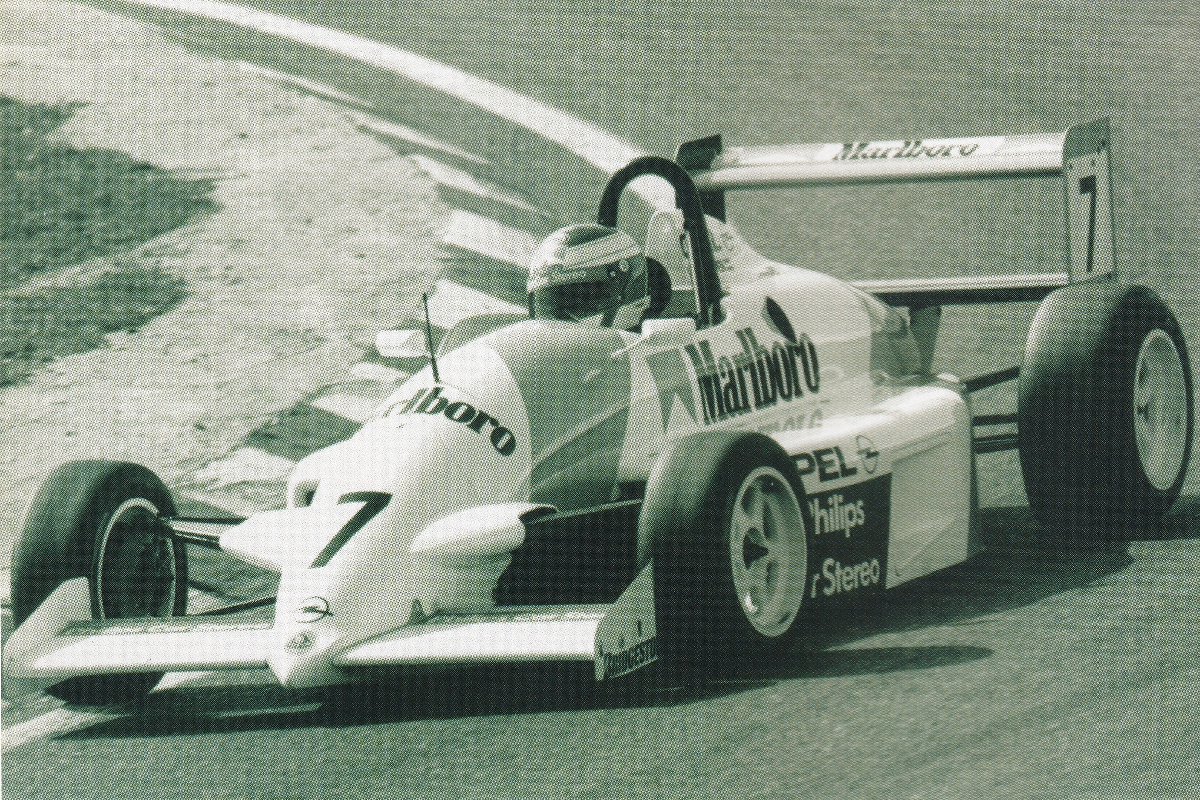

At Zolder’s Euroseries double-header in September, Verstappen was unstoppable. Yes, he had raced there three times previously that year, but his dominance still stunned observers. In wet qualifying for race one, he was fastest by 1.3s; in dry qualifying for the second race a mere 0.5s. And in the races, he simply disappeared into the distance winning by 18s and seven seconds respectively. The sheer scale of his margin prompted paddock mutterings about the legality of car and engine.

“We were sharing a pit box with David Sears Motorsport, everything was much more open than now,” remembers Niessink.

“The next morning we came back to the track and Sears said to us: ‘Listen, you guys had left already last night and I took the cover off your car and I measured everything and the car is legal. Everything is normal, it’s standard.’

“The next morning we came back to the track and Sears said to us: ‘Listen, you guys had left already last night and I took the cover off your car and I measured everything and the car is legal. Everything is normal, it’s standard.’

“We said ‘Yeah, we could have told you because the only thing which might be illegal is the driver sitting in the car’, It was really astonishing how good Jos was already.”

The season finished at Estoril with the final round of the Euroseries and the Nations Cup, where two-car teams ran in national colours; orange, naturally, for the Dutch team of Verstappen and Martijn Koene.

“We brought two cars, one was a used car and I built a new chassis over the weeks before,” Niessink explains. “I really had the time so I did a really perfect job. And together with Huub they went out to drive around with a rental car and, I don’t know which corner it was, but he did the corner in fourth gear or something.

“And then he went out with FOpel car and he never came back again because he completely misjudged the corner based on the information he had from that rental car.

“So we had to swap to the other car because it was completely destroyed. But then with the old car he simply won everything, you know, he was always there.”

The Netherlands won the Nations Cup, while in the final Euroseries round Verstappen fought back to ninth having started 18th as a result of his practice crash.

Like all top drivers, his peripheral awareness was outstanding. Niessink recalls being with Verstappen at Zandvoort during qualifying “and he would come back and say, ‘my father is also here at the circuit, I saw him standing on the dunes’.

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

“In my idea, recalling what I did when I was driving, you’re focused on driving but Jos he could drive a car [and be aware of other things].”

After taking in the Formula Pacific series in New Zealand, Verstappen moved up to German F3 for 1993, joining the works Opel WTS team run by Michael Schumacher’s then-manager Willi Weber.

Expectations were high but the start of the season featured incidents, collisions and spins aplenty.

“Jos is someone with perhaps too much ambition and too much energy,” team boss Weber observed at the time. “He showed that in the opening races which were, in the main, disastrous. But he changed his approach, and I am confident that he will win the championship.”

Verstappen admitted to being too aggressive in the early rounds but said “if you are not aggressive you won’t win any races”.

Having toned down his over-forceful approach, he took two podiums in round three at the Nurburgring. By the following round on the Wunstorf airfield circuit, it was clear that Verstappen had fully taken on board the lessons, calmly dominating both races from start to finish.

From then on, his march to the title was imperious, taking a further six wins and three second places in the next 10 races, to wrap up the title at AVUS in Berlin with one round remaining, fully justifying Weber’s faith in his talent.

Verstappen shone in the year’s blue-riband F3 events, finisning third behind Italian F3 runners Gianantonio Pacchioni and Giancarlo Fisichella in the Monaco Grand Prix F3 race, and he won the Masters of F3 on Zandvoort’s short Club layout.

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

At Zandvoort the world got its first taste of Verstappen-mania, albeit without the flares, techno music and sea of orange. With Marlboro backing both driver and event, the publicity surrounding the weekend was huge. And Verstappen did not disappoint the 56,000 spectators – an impressive attendance for a F3 race. Having edged Paolo Coloni for pole, he kept his cool to take a lights-to-flag victory over the Italian by 2.5s.

“The car was perfect. I didn’t make one mistake. I was very happy,” said Verstappen after the race.

F1 beckoned. Verstappen was the hottest property in junior single-seaters. After tests with Footwork and McLaren, he was snapped up by Benetton as a test driver for 1994. When regular driver JJ Lehto crashed in pre-season testing, Verstappen was drafted in to make his F1 debut in the opening race of 1994 alongside Schumacher.

Incredible natural speed allied to an aggressive, sometimes impetuous approach to racing. What was Verstappen like to work with?

Although VAR were actually one of the first teams to mount a home-built data system to their cars including transmitter, Verstappen was, says Niessink, “the type of driver that didn’t need any data systems”.

“He was already fast enough simply on his natural speed. He came in and told us ‘I have understeer or oversteer’, and then we decided for a rollbar or another set of tyres and whatever and he went out and he did it.”

In Niessink’s opinion: “[Jos] wasn’t really convinced he needed to work hard, because he never learned to do so, because his natural speed was always enough. And then when he ended up in F1 all the systems were there and then he started to work for it, but he was more easy-going.”

Natural talent can only get you so far in mtoorsport, a lesson that Verstappen took onboard in bringing up son Max.

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

Because Verstappen had never needed to analyse every detail in the way that, for example, his 1994 Benetton team-mate Schumacher did, “he didn’t really practice it,” says Niessink.

“And I think because of that experience and because Jos is smart enough to understand why he did not do the maximum himself, he was really focused on making sure that Max would do it and that’s where he made sure all his experience before is introduced into Max, and that’s why Max is so successful.”

Out of the car, Verstappen “was I would almost call it shy [but] he was not shy when he was in the car. But he wasn’t sure, so he wasn’t that demanding to the team at that stage. But he was extremely demanding when Max was with us in the team.”

Verstappen returned to his former team 22 years later when his son stepped up from karts to cars, with a few weeks spent in the entry-level Florida Winter Series before he jumped up into the FIA European F3 championship. Father and son shared a level of determination, focus and competitiveness “that is really extreme”.

“It starts with not accepting defeat. You know, only winning is good enough. They would never ever say in qualifying ‘I’m P2 but you know it’s only four-tenths or four-hundredths of a second’. No, it’s not good enough,” Niessink emphasizes.

He cites the example of the 2014 Macau Grand Prix which Max Verstappen went into as hot favourite.

“We were at Macau, there you have the Saturday [Qualification] race, and we were talking about ‘if you’re in the top three, then in the main race with overtaking and the slipstream etc.’, and Jos goes ‘what do you mean by top three is good enough? Don’t be ridiculous, we need to win’.

“We were on our way to come home second in the Saturday race where we know we would have absolutely won the Macau race on Sunday. [But] for the simple reason that only winning is good enough, Max crashed the car when P2 and on Sunday he came from the back to P7, then had to do it again because of the red flag. We would have won it.

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

“That’s what by nature is in them. It’s such an extreme winning mentality that goes beyond anything you normally see. That ridiculous drive is in both of them. They do not accept not being first. Everything needs to move over to achieve that and that goes to a level which you can hardly imagine.”

On top of his “his raw natural speed, his talent, his physical [preparation] and his intelligence”, Verstappen had the benefit of father Jos’s experience.

He has been brought up to understand that “success only comes with hard work”, says Niessink.

“They call you at the most ridiculous hours of the day to ask ‘how we can do this?’, or ‘how can we do that?’.

“If you reply ‘sorry, I am doing this now’, the response would be ‘yeah, that way we’ll never win’. You know, everything needs to move over for the win.”

Jos Verstappen himself is famously reluctant to look backwards. In effect, Max is continuing and perfecting Jos’ own racing career. Never short of talent or bravery, maybe “Jos The Boss” was too impetuous, too close to the limit and too laid-back to go to the top in F1, although he is one of only five drivers in the last 50 years to get two podiums in their first seven starts. But maybe being paired with Schumacher in your debut season would have broken any driver.

There is no doubt that 30 years ago Jos Verstappen was one of the hottest prospects in junior single-seaters. He deserves to be remembered in motorsport terms as being more than ‘the father of Max’.

More Dutch racing history

Remembering Marcel Albers, the Netherlands’ lost champion

Book review: How MP Motorsport grew from its FFord origins

Tom Coronel on his racing addiction, Merc’s “insurance” driver and more