Photos: Roger Gascoigne

His son may have got to F1 as a driver, but it’s Ralph Firman Sr who has one of the most envious pedigrees in racing through his Van Diemen company and its many single-seater creations since 1973

At last October’s Formula Ford Festival, Formula Scout sat down with Van Diemen founder Ralph Firman to talk about the legacy of the racing car manufacturer he created in 1973 and the cars he produced that are still racing today.

Last month’s BRSCC National FF1600 season opener at Silverstone featured six Van Diemen chassis, as well as six Medina Sport-branded cars from a manufacturer which took on a loose ‘continuity car’ design philosophy from where Van Diemen left off. Later in the season there will be the return of the ‘newest’ Van Diemen, Team Dolan’s heavily developed BD21, as well as at least one car from the successor brand Firman created under his own name as a rival to old Van Diemens and Medinas.

Even the vehicles stemming from 22-year-old designs are considered contemporary single-seaters, as research and development done in the past has made sure these cars are still competitive in the present. It’s not just FF1600 where Firman’s two companies have designed cars with long lives, and it’s not just in the United Kingdom where his cars race today.

“We made many different types of cars and one-make formulas,” Firman recalled.

“We sold cars to Ford Motor Company, Nissan, Honda, and Renault. But FFord is our sort of thing. We used the factory team as a marketing tool. We were fortunate enough to have Duckham’s oil as a sponsor for many, many, many years and it kind of all fitted into what we wanted to do. And it obviously fitted in with their [ambitions].”

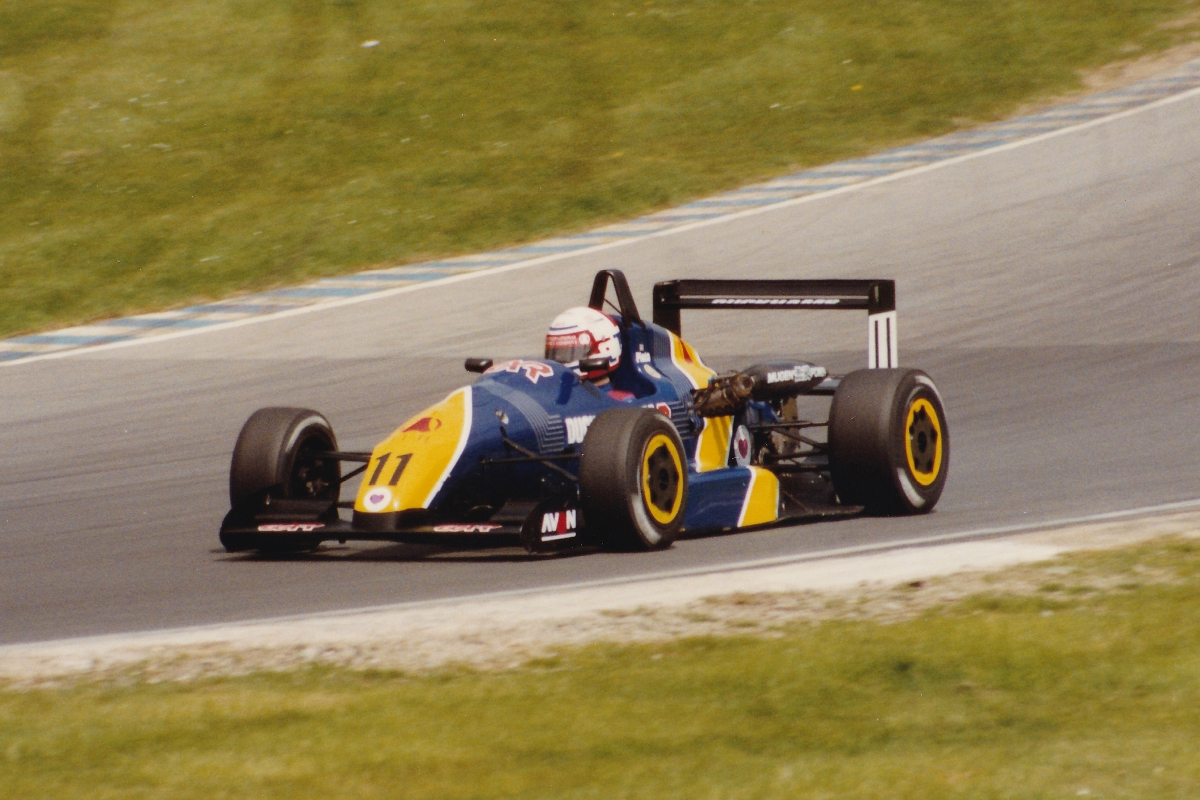

The blue-and-yellow Duckham’s livery on the factory Van Diemen cars in various categories is one of the most iconic visuals in junior single-seater history. Future Formula 1 and IndyCar stars were hand-picked to drive for the factory team before it dissolved in 2001 with the company sold on to Don Panoz to become part of his Elan Motorsport Technologies group. Comtec emerged from the team’s ashes and rose up the single-seater ladder over the next decade, while the Van Diemen name was used for new junior series chassis during the same timespan, primarily for spec series in America.

Jason Plato in Van Diemen’s 1992 F3 car

That moved the R&D focus away from Snetterton, Van Diemen’s local circuit for the previous three decades and where many racing cars were first tested before appearing on the market after Firman somewhat popularised the venue’s potential.

“We were fortunate with Snetterton because it wasn’t busy like it is now, and we could virtually go over any day we wanted and test. We’d test engines, we’d be testing gearboxes, we’d be testing exhaust systems and so it goes on. New cars and new thoughts, just to keep going forward. And it meant that when he brought another car, another design, the customer got a sorted car. So we’ve done 1000s of miles of testing there.”

One of the last cars to be put through its paces at Snetterton was 1999’s Van Diemen RF99, still one of the most popular chassis in FF1600 in the UK and one which has possibly had more success than any other in the modern era courtesy of Dolan driver Niall Murray. After several years of tinkering, taping and titles, the development of the Irishman’s RF99 led to his chassis being entered as a BD21 last year. Dolan, which is based in Snetterton, plans to have Murray back on track soon.

“Because I was selling the company, I kept going with that new design [the RF99] – and there was a question about that because we were spending quite a bit to develop it,” Firman says. “We were getting into aerodynamic work and wind tunnels and all sorts.

“We talked in the company about ‘well why are you doing that if it [the company] is selling’. I said ‘just in case it doesn’t go through’. I said ‘if it doesn’t, it will take us another two years to develop, and then we’re going to have a big fall in’. So that was a brilliant car, and has been [since]. Everyone now has developed shock absorbers and springs and bits and pieces, but there hasn’t been that much development. It’s just more the type of thing that, as you keep racing the same car and the drivers get used to it, then [it gets improved] – but it’s mainly just in controls, with damping and stuff like that.”

Firman says the Medina Sport chassis of the last decade “basically is a knock-off of that car anyway”, and when Formula Scout more kindly puts it to him as a set of continuation cars the reply is a friendly and knowing chuckle. With the BD21 though, according to Firman, “they’ve got a good system now where they can change the wheelbase for different circuits”.

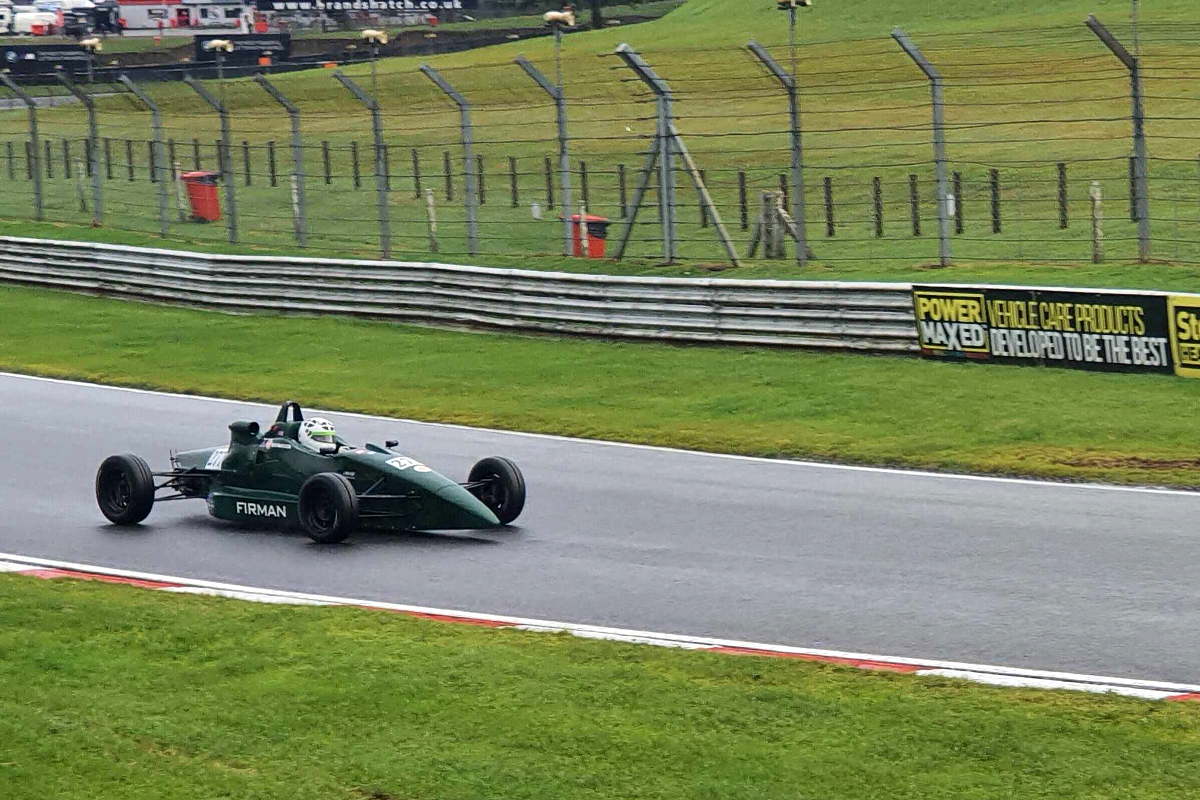

Photo: Jakob Ebrey Photography

Such a system must be within the rules for the car to have run without controversy, and no doubt other manufacturers have wheelbase solutions too – although there are drastically different design philosophies in the UK FF1600 paddocks when it comes to optimum wheelbase for a car – but it shows how much development is still going on in this wingless category even if Firman himself underplays how much R&D work is taking place in modern FFord racing.

“If we’d have continued as a company, who knows what we could have turned up with,” Firman says of what a truly modern Van Diemen would have looked like had the company not been sold on 20 years ago.

“But people like Reynard, who were really a good company, had gone out of FF1600 by that time and I don’t think you’d see any of these little companies [emerging]. Who knows [how FF1600 could have looked]? I don’t. I can’t answer that question.”

There is one big visual change to FF1600 that may come in the future if it is to remain a category that attracts budding single-seater drivers and teams with dreams of moving up the ranks, and that is the halo cockpit protection device. It is not a topic talked about much, but its incorporation into FF1600 would be looked on very positively by sanctioning bodies.

“If they wanted halos, then there would be a completely 100% redesign. I was asked in the United States about ‘can you just sort of weld some brackets on’ – and this is a few years ago but then COVID-19 hit so we haven’t had talks since – but the SCCA’s (Sports Car Club of America) attitude at that time was, providing that the brackets have been looked at by an engineer, it would be alright. But it wouldn’t be alright.”

The only car to have truly been retro-fitted with a halo is Dallara’s Indy Lights car, with greater adaptation to design of the monocoque and other components needed to add it to other single-seaters. With FF1600 cars and their Honda-powered US counterparts being considerably smaller and non-identical as it remains an open formula, it makes it far harder to add.

“Well apparently, that was that,” Firman says as he continues the story of SCCA’s halo plans. “And I said ‘but [exasperated sigh]’ and they said ‘well would you just put the halo on a car’. I said ‘no! It wants designing from scratch, so we know where the loads are going and so on and so forth’. It’s not magic, it’s just pure engineering.

“Well apparently, that was that,” Firman says as he continues the story of SCCA’s halo plans. “And I said ‘but [exasperated sigh]’ and they said ‘well would you just put the halo on a car’. I said ‘no! It wants designing from scratch, so we know where the loads are going and so on and so forth’. It’s not magic, it’s just pure engineering.

“And I think that’s one of the areas that we’ve had great success with. It’s that all of our cars were engineered and designed correctly, and the chassis were safe. And if you look at the records, with the amount of cars we built, the injury level is very low. And it’s something that people then took for granted.

“But lots of other… even the SCCA, the Formula Enterprises [for example]. We built a one-make car for them, and our brief was ‘we want to put in a 150 horsepower engine’, and they tell me now it’s got a 250hp engine. That’s a car that we built 20 years ago, and we supplied 100 of them. These people, they disgust me actually, that they’re doing that. But the chassis have stood up to it.”

It may be annoying from a manufacturer’s perspective to hear of a design being taken out of the parameters it was built for, but there’s a definite danger attached to taking a car engineered around having a certain power and certain weight, and then just adding more to that. “Of course,” Firman agrees. “And the big safety factor.”

Ralph Firman Racing was created in 2008 to continue Firman’s car-building efforts, back at Snetterton, and he created popular chassis for FF2000/F2000 and the bike-engined F1000 category which have already appeared all over the world. After creating the car for BRDC British Formula 4 (which then evolved into Formula 3 and GB3 and took on Tatuus chassis), Firman’s latest project has been another FF1600 design: the RFR17.

“We did well with the F1000 in America, because we really did find a good team to run the cars. I think we won the SCCA National Runoffs over there for two years. The F1200 car, it needed some development. And we weren’t lucky enough to have a team that was really dedicated to that, and the FFord is the same [now]. We built it, but it still needs some development, team development if you know what I mean. Although it won the British championship the first year we built it!”

Luke Williams was BRSCC National FF1600 champion in 2017 with the car, while in recent years it has been Jack Wolfenden and also the Don Hardman Racing team that has committed to running it. Only a handful of chassis were built to begin with.

Luke Williams was BRSCC National FF1600 champion in 2017 with the car, while in recent years it has been Jack Wolfenden and also the Don Hardman Racing team that has committed to running it. Only a handful of chassis were built to begin with.

“I could see that the market had changed,” Firman explains. “I mean every year, serious teams bought new cars. And of course at that time you’d still got FFord in the rest of the continent, Australia and so on. But you’re never going to make a profit if you haven’t got volume. You need volume to keep the price down.”

In today’s world, economies of scale means providing a car for a spec series makes financial sense. Building individual cars for FF1600 customers – a strategy B-M Racing has with its Medina Sport chassis – is harder to make workable.

“At the time we sold [the company], we had a brilliant machine shop, modern machinery and very good people in fabrication and body-building. The company was run very well. So, yeah, [when making the Firman car with less resources] I decided ‘well look, I think I’m on a hiding from nothing here’. But we’d still taken an interest in it, with the odd people who are running the cars. If they want to keep running it, then we’ll give them any help that they want.”

DHR plans to do a part-time National campaign before the FFord Festival and Walter Hayes Trophy, and category legend Joey Foster will be at the wheel of its finetuned RFR21.

“Now the COVID-19 pandemic is sort of going over, because we lost two years [of development] really, and we can spend more time putting some time into it and working with [DHR],” Firman continues. “So, yeah I look forward to 2022 with Joey, and he wants to persevere, and that will be good.”

The Firman workshop is ready to spring into action and start producing more of its most recent model, but the boss doesn’t want to put cars out “in ones and twos, like these littles companies are doing now; because you just can’t get it down to price”.

What would be a sustainable production number for Firman to get manufacturing full cars again?

What would be a sustainable production number for Firman to get manufacturing full cars again?

“If we could look at 20 a year. Because in America, FFord is starting to become strong again and people want to run them. 20 a year would be a reasonable figure.”

While that would be scaling up now, it’s a massive scale down on the level of output Van Diemen had in its heyday as a profit-making company with customers across the globe.

“We had 40 people working there, and we were producing anything from 120 to 180 cars a year. And what we made was very cost-effective. Which in many ways we passed it on to the customer, and we were quite happy to do so because we’d got the volume. We knew what profit we wanted, and we just kept up, kept pushing. But we spent a tremendous amount in design and development, on lots of different projects.

“We made 90% [of each car] in-house” and used the 100% scale vehicle wind tunnel at the MIRA engineering R&D base for aero testing.

“It wasn’t ideal because it didn’t have a moving floor,” says Firman, but using the MIRA facility – located 120 miles west – proved incredibly useful “because we weren’t particularly looking at downforce and floors and stuff, we just wanted to look at the bodywork itself and that’s what we did and spent a lot on that RF99 car.”

The result with that car was improved straight-line speed and cooling, a feature which has marked it out to this day in the paddock during hot summer races.

Just like F1 teams at the time, this 1990s FFord car was a product of computer design as well, having been developed with computational fluid dynamics (a way of simulating airflow against a digital model of a car) after designs were done digitally.

“A lot of the designs were done from the mid-90s, and maybe early ’90s, on CAD. I got them working with that probably 1991, ‘92. But our head designer, David Baldwin, he still preferred to use the drawing board, a bit like Adrian Newey. And David was old-school like that, I was never going to get him doing a lot of CAD work.”

While firmly established in FF1600’s past, it’s very possible that Firman may just keep his hand in for the category’s future, and there are other brands, such as Ray, Spectrum and Swift in the UK, already pushing each other hard in the makes’ race.

Listen to our interview with Ralph Firman in podcast form below, or find it on Breaker, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Castbox, Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

More from Formula Ford

The talking points at FF1600’s first big weekend of 2022

GB4 to run £20,000 prize shootout for top teenagers in National FF1600

Where Motorsport UK is pushing with its plans for Britain’s junior ladder

Podcast: Roberto Moreno on his nostalgic FFord Festival comeback

Why two great Danes’ “just for fun” return was a serious Festival attack