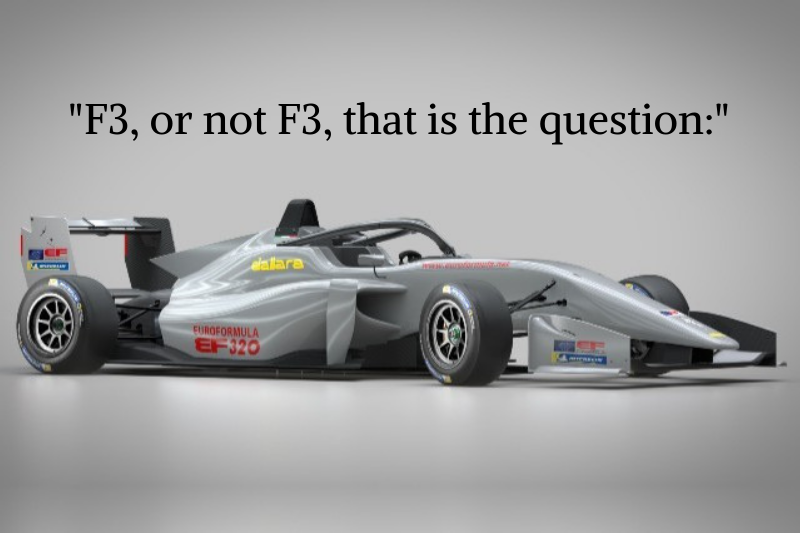

Dallara has introduced a new single-seater car which could be racing in Europe and Japan next year. It’s not called Formula 3, but it may well be the final product of its legacy

Nine months ago, the future of Euroformula Open – a continental Formula 3 championship – was laid out by series promoter Jesus Pareja to Formula Scout in a exclusive interview. The primary ambition was to preserve ‘traditonal’ F3 and its open-engine formula, a procedure the championship has mostly implemented with success.

There was one line which, more than 2019’s introduction of multiple engine suppliers, will shape the future of third-tier single-seaters for years to come.

“What we’re looking for in our series to keep the parity, to open the possibility to other teams, our target is to get three more teams for 2019, and maybe introduce a new car for 2021.”

Euroformula has ticked off the first two points in principle, and with the introduction of the Dallara 320 for 2020 it’s now embarking on the third.

At the time of the interview, representatives from Euroformula, FIA European F3 and Japanese F3 were approaching Dallara to provide a new chassis that continued the “spirit” of the existing Dallara F317 car all three used. And as any good salesman will tell you: the customer is always right.

The homologation of the F312/F317 chassis ending in 2019 meant plans for a new car had to be brought forward a year to ensure FIA International series status could be retained. This came hand in hand with the introduction of the halo cockpit protection device.

“The idea grew from people saying it would nice to find a solution to continue with this [F317] car,” Dallara project manager Jos Claes tells Formula Scout.

“But you cannot put the halo on this car. I understood the [customers’] message, which was: Is there another way? Is there a solution?

“At that point, we were studying whether to build our Regional F3 car. Should Dallara, one year late, enter the market?”

Tatuus had been the first manufacturer to build a car to the Regional F3 regulations, and had already captured the market in three continents. The Regional F3 concept did not appear to be catching on in Europe, until the Formula Renault Eurocup and W Series both changed plans in October to use the Tatuus chassis.

This prompted a strategy reevaluation at Dallara, and the solution proposed by Claes was to study if a new halo-carrying monocoque could be built to fit around the mechanics of its existing F3 car. Ultimately it came down to supply versus demand, and once it became clear it was technologically achievable, it was down to the customers whether it was attractive to them. The answer was an unsurprising yes.

During the design process, Dallara realised it could escape the restrictions of the FIA F3 regulations, and built a car to Formula 1’s 2018 safety standards.

This opened up the materials and techniques that could be used, and ensuring that despite the introduction of the halo the car will remain at the current 580kg minimum weight with driver, and thus retaining the ‘spirit’ of F3.

The bodywork is all-carbon fibre, the skid block has been removed, and with the option of switching to even lighter batteries and exhausts there’s room for further weight saving. Not to mention that many F3 cars actually run ballast.

These small changes, some carried over from technology used in Dallara’s recent Formula 2 and Super Formula designs, make this car arguably technologically superior to the new FIA Formula 3 Championship car.

But, while the car has been named ‘320’ to show it’s an evolution of Dallara’s F317, it is not a Formula 3 car. And to further confuse matters, any owner of a Dallara F312/F317 can adapt their current chassis into a 320.

“There’s a list of the parts we sell as a kit, and all the rest is from the F317,” explains Claes.

“We sell them a new monocoque. Inside that monocoque is a new safety seat with 25mm safety foam. That is something we add that is not in the F1 regulations, we added for extra safety. There is a new fuel cell, that goes from FT3 to FT5 standard. Obviously [there’s] the titanium halo. We do everything to keep the weight down, so we picked titanium as it was 7.5kg less than the steel halo. That’s the monocoque.

“Attached to the monocoque in front is a new nose box, because F1 front impact structure is different. There’s also [improved] side and rear impact structures.

“Nearly the complete bodywork has changed, so new floor, sidepods, new endplates, new engine cover, but not the front or rear wing profiles.

“As for the rest, the front suspension is taken over, the pedals, other details inside the car, the fuel system. Then from the back of the monocoque, you unbolt from this car and you bolt it to the new monocoqoue and your complete rear end is done. Because engine, bellhousing, gearbox, rear suspension, electronics: all identical. Then the car is ready.”

Some teams still run components built for the F312, and two of the first F312 chassis raced at the Macau Grand Prix last year. By the 2021 season, there could be parts that will be covering a decade in service.

“There’s a lot of components in the car that even after years of racing now, they have not suffered from anything,” says Claes. “You can just carry over.

“Nobody is running the suspension on the F312 from 2012, because every corner has been crashed at least once, I would say, in eight years.”

With such a high carryover of existing parts, it means the stock of spares for drivers continuing to run even the older F312s in the likes of the MSV and Remus F3 Cups can buy brand new Dallara parts for the indefinite future.

Photo: Fotospeedy

The upfront cost of purchasing the new monocoques will obviously be an increased cost for the teams, mostly down to the strengthening to meet F1 standards, but there is nothing to suggest running costs will follow suit. And as for the teams, they don’t seem to mind anyway.

“I think the concept is great. It’s the right way to go, because the current car is the best to educate drivers. It’s been proven for years and years,” Timo Rumpfkeil, whose Motopark team runs in both Euroformula and Japanese F3, tells Formula Scout.

“[Euroformula’s] Michelin tyre is very positive for the drivers. We made the championship switch from a different brand [FIA European F3 ran Hankooks], and just from replacing the tyres to Michelin, it’s so much more positive for the drivers. So the whole package grows because of that.

“They are doing the right steps by not increasing weight, because all the other cars are much more heavy. And having more efficient aero on the car. Of course it comes at a cost, but I prefer to pay more initially and have a good quality product rather than buying bits and pieces over the season.

“We did [ADAC] F4 for quite some time, and that car is built to a budget. Which is good in one way, but in the end there are components on the car that you have to replace so often that then cause more costs in the long run. So I prefer to have a good Dallara-quality car and happy to pay the price on it initially, than have that sorted over the cost of the season.”

Photo: Fotospeedy

The enthusiasm from within the paddock seems to initially be matched by the public, with a common theme that this is the first halo-shod single-seater that truly resembles what most think of as an F3 car.

As Claes points out, regulations define a lot of the styling of modern cars, and therefore it’s no coincidence it shares much of the same profile of a 2018 F1 car.

If the minimum weight does indeed remain unchanged, then the performance could improve too. The halo takes away rear downforce and significant drag, but work on the underside of the car means its more aero efficient than the F317.

It may not be as high-profile as Dallara’s contracts with F2, IndyCar or Super Formula – the latter of which had similar philosophy where the customer pushed Dallara for an innovative design – but in providing a popular answer to the FIA’s requirement for the halo and purists’ desire to maintain ‘traditional’ F3 it could once again become the de-facto third-tier machine for championships across the world.

It will be difficult, especially with Tatuus’s spread of customers and the fact Japanese F3 organisers – who are set to change their championship’s name to Super Formula Lights for 2020 – are yet to formally pick the 320, but this is a car that’s gone for quality rather than quantity, and is working with a championship that doesn’t judge its merit through the prism of the FIA superlicence alone, and is flourishing all the more because of it.

And in this instance, if it’s providing great grids in exciting cars and on a variety of much-loved circuits, then it doesn’t matter if it’s not called F3.

Photo: Fotospeedy