Photo: Roger Gascoigne

Prema started off in Italian F3 in 1984, and became a title-winner in 1990. Staying on top in racing proved difficult over the next 20 years, but the team’s since become a dominant force in multiple categories. How?

The period after Prema won its first junior single-seater title in 1990 may not have been defined by the success we know it for today, but was the genesis of the operation as it is now: a colossus towering over multiple series in multiple continents. Having begun as an F3 team, Prema expanded into categories up and down the open-wheel ladder, and success followed it.

In part two of the story of Prema’s early years, we talk to Prema’s co-founder and family patriarch Angelo Rosin about how the team gradually rebuilt itself at home and abroad.

Since Formula 1 got into the idea of young driver development programmes, its teams have entrusted the development of their junior drivers to the “Prema school”. In fact, Prema was there from the start in Europe for modern manufacturer-backed talent academies, which began with Japanese brands Toyota and Honda at the start of this millennium.

Rewinding to the end of 1993, Prema was a team that had won just three races in three Italian F3 campaigns since Roberto Colciago had delivered it the 1990 title. However, with new investors and a new base, hopes for the 1994 season were high.

Regaining the team’s title-winning status was not straightforward. European karting champion Federico Gemmo had joined the team, but podiums were scarce and he was replaced mid-season by Andrea Boldrini, whose victory in the last round prevented Prema from suffering its first winless season since 1991.

In 1995 Gianantonio Pacchioni returned after two years racing for rivals, and took four wins en route to third in the standings.

“Pacchioni always drove very well on the small tracks,” Rosin says, as if to illustrate that his four wins in 1995 came at two of Italy’s smallest circuits, Varano and Misano.

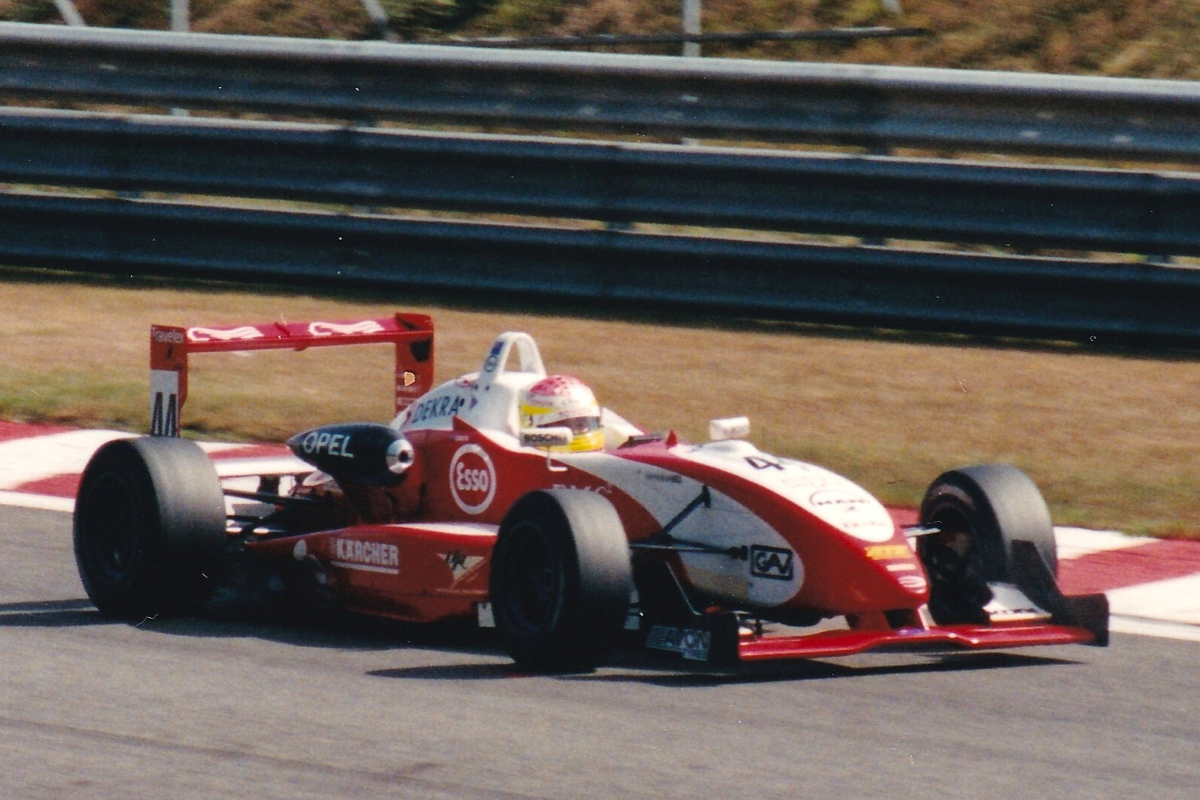

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

Pacchioni’s true speciality was Monaco, of course another small track, where he led start to finish in the grand prix-supporting F3 race to beat Ralf Schumacher to victory by half a second [pictured above]. Prema had won the 1989 edition of the race, and Monaco where it could make an impression on an international level.

Back home in Italy, Prema’s co-founder Giorgio Piccolo – who had left the team in 1994 – made a surprise return in 1996 to manage its planned expansion to Formula 3000. When that fell through, he ended up back in charge of its Italian F3 entry.

“There were five of us, including the driver, Joao Barbosa. A fantastic work group. We won a wonderful race at Varano [when Barbosa started on slicks on a wet track and lapped the field] and came second in the championship. A fantastic experience.”

By now, however, Italian F3 was a pale shadow of its former years, as talented Italian drivers such as Jarno Trulli opted for German F3. And so Prema made its first foray abroad, joining the German championship with Andre Couto and Max Wilson.

Wilson took Prema’s first win at Diepholz but the transalpine sojourn was short-lived, as Prema withdrew at the end of 1996.

Picking the right engine partner remained critical in F3, then an open category, as Rosin explains. “In 1995 to ’96 [Novomotor’s Gianni] Pedrazzani pushed us to an evolution of the electronics [for the Fiat engine]. Prema invested money into the organisation bringing in some people. But it was difficult because in that period Opel had a very good engine, with a very good development of the electronics.”

For 1998, Prema joined the growing exodus to Opel power and soon returned to winning ways at home, taking the Italian F3 title with Donny Crevels that year and with Peter Sundberg in 1999.

Despite the team’s successes, it was clear that the writing was on the wall for Italian F3 “and so we decided to stop with F3 in Italy because in this period F3 in Italy had a very low profile, a very low level, and moved full-time to Germany with [Enrico] Toccacelo and [Philip] Cloostermans”, with Toccacelo winning at the Nurburgring in 2000.

Photo: Prema

Then in 2001, Prema embarked on its programme of developing young drivers for manufacturer-backed programmes, which would contribute to its rapid growth over the next decade.

The liaison with Honda meant Formula Dream champion Kosuke Matsuura, a protege of ex-F1 driver Aguri Suzuki, joined Prema in German F3 for 2001 alongside Bjorn Wirdheim.

But the tie-up with Toyota proved more durable and brought Prema its first major international success. Toyota’s Prema-run programme broke new ground in developing junior single-seater drivers in Europe, creating a template for others to follow, and led to Prema’s first step beyond F3 into Formula Renault 2.0 as Toyota sought to evaluate talent in lower categories.

“Toyota came to us to organise the Italian FR2.0 with Ryan Briscoe and Ronnie Quintarelli. During his title-winning FRenault season in 2001, Toyota decided to give Briscoe an F1 test and decided to skip F3 and move him straight to F3000 with Nordic Racing, championship winners with Justin Wilson. They expected bigger results but after five or six races, they decided to stop because the results were very, very bad,” Rosin recalls.

“So, they came back to the German F3 championship with Prema. It is difficult to restart in F3. Toyota decided to give him one last chance to drive in F3 in 2003 and he won the F3 Euro Series.”

In his sophomore season, Matsuura was German F3 runner-up as Briscoe played himself back in with three late-season podiums. But the decline of F3 championships had proved to be a multinational rather than Italian phenomenon.

For 2003, French F3 and German F3 combined to create the Euro Series which Briscoe won. His campaign featured eight victories, and team-mate Robert Kubica won on debut at the Norisring, having broken his arm in a road accident at the start of the year and missed the first three rounds. Briscoe’s triumph was Prema’s first title outside of Italy.

Photo: Prema

One rung below, Prema took another Italian FR2.0 title with Franck Perera, then a third in 2005 with Kamui Kobayashi who also won the FRenault Eurocup that year aged 19.

“My racing career in Europe started in Prema. I worked with Prema for two years. At that time the championship was very competitive, and it was the first time Prema had won a European championship. [We] made history and I’m very proud to be part of this game,” says Kobayashi, who is now Toyota’s World Endurance Championship team principal.

Briscoe’s success did not herald an era of Prema dominance in F3. In fact, the team would surprisingly win only five races in the next seven seasons as ASM Formule 3 (which later evolved into ART Grand Prix) dominated the Euro Series with Jamie Green, Lewis Hamilton, Paul di Resta, Sebastian Vettel, Niko Hulkenberg and Jules Bianchi from 2004 to ’09.

Toyota junior and series sophomore Perera came fifth in the 2005 standings, then Renger van der Zande ended Prema’s winless streak of close to four years at Barcelona in 2007. He took two more wins and third in the standings in 2008.

After Opel withdrew factory support for its teams at the end of 2004, Prema’s rivals using the HWA-developed Mercedes engine became untouchable.

In fact, as Rosin relates, “Gerhard Ungar from HWA-Mercedes [now the co-owner of US Racing, one of Prema’s biggest F4 rivals] gave me a proposal: ‘I want you to come to Mercedes. I will give you support’”.

But Rosin’s hands were tied by his commitment to Toyota. “With Toyota it was impossible. Toyota said no because they were fighting with Mercedes in F1, two big [automotive] companies. Toyota paid for seven drivers, so it was difficult to say no, to turn down Toyota to move to F3 with maybe two or three drivers.”

After a change in management personnel at Toyota in 2005, Rosin said “sorry, I’m not interested in driving for Opel; I’m moving to a team with Mercedes”. However “it wasn’t possible to change immediately, so we continued to stay with Opel”.

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

When Prema finally made the switch to the now-dominant Mercedes engine for 2006, Rosin recalls that Ungar said to him: “You refused many times my proposal. Okay, welcome but now you stay like this.”

Mercedes, and subsequently German rival Volkswagen, began to use F3 for developing young drivers, not only filtering the best talent for progression into their DTM teams or to F1, like in Hamilton’s case, but playing a role in allocating drivers to favoured teams in F3.

“Had I signed earlier, I [would’ve] received the same proposal in the same moment as ASM,” says a rueful Rosin. “All the good drivers he moved around the company. I received one driver, but it was not the best driver. But things changed a little bit when they understood the potential of the relationship.”

Indeed it did, and the partnership with Mercedes continued to blossom, forming the foundations for Prema’s return to the front of the field.

GP3 was launched in 2010 and the new F1 support series immediately attracted ART GP. It was out of F3 a year later, while Prema remained loyal to the category.

The recruitment of experienced and talented senior technical personnel, allied to new investment, provided Prema with the infrastructure to dominate the 2011 and 2012 seasons, with Roberto Merhi and Daniel Juncadella its two champions. Juncadella rounded off his title-winning year by finally taking Prema first win in Macau to the team’s delight and relief.

Almost as if winning Macau had been a mental barrier to overcome, victory there provided the catalyst for Prema to forge ahead. The floodgates opened and trophies have been flowing towards Vicenza ever since.

In 2016, Prema expanded into single-seaters’ second tier and finished one-two in its maiden GP2 season with Pierre Gasly and Antonio Giovinazzi. It has remained there ever since, with the championship now known as Formula 2.

Photo: Formula Motorsport Ltd

Prema had made multiple attempts at taking the step up before. In 1992 a plan to graduate with Jacquess Villeneuve was scuppered when he opted for a lucrative offer to race for TOM’S in Japanee F3, and the 1996 attempt foundered despite having enticed Piccolo back as team manager for the stillborn project.

Then in 2006 it purchased DAMS’ entry in FR3.5, the rival series to GP2, and spent four seasons there with a return of five wins, three poles, five fastest laps and 19 podiums as well as the championship runner-up spot with Ben Hanley in 2007.

By the early 2010s the financial future of the team had been secured through a significant investment from Lawrence Stroll, now executive chairman of Aston Martin.

Rene Rosin, the son of Angelo and his wife Grazia Troncon, gradually took over at the helm from 2006 before assuming overall responsibility as team principal from 2011. Prema also strengthened its technical team through some significant new hires.

The rest, as they say, is history.

“Things changed a lot when Mr Stroll came,” says Rosin Sr. “Prema is a good step to get the mentality. Mr Stroll chose Prema because he saw the result of the work is good.”

Stroll’s involvement “was very important” in setting the foundation for the huge growth in Prema’s strength, reputation and successes across almost all categories of junior single-seaters, something which has been taken to the next level in the tie-up with Iron Lynx under the DC Racing Solutions structure.

From a staff of five in the 1980s, Prema recently counted 144 trackside personnel over a single weekend as it embraces multiple single-seater championships as well as the prototype sportscar programme it added in 2022.

Troncon with a former F4 crop (L-R) Schumacher, Correa & Vips

At heart, it remains a family business. Angelo and Grazia are still trackside, looking after the Formula Regional and F4 teams. Their good spirits and passion for the sport underpin Prema’s philosophy.

Though its level of professionalism and technical excellence continues to set the benchmark for other teams, and not only in the junior categories, Prema has managed to retain the sense of the small Italian garage team, still smiling and laughing even when crushing the opposition on the track.

“I never imagined that it would become so big,” says Rosin. “For me, to stay in motorsport, when you stay with two cars in F2, two cars in F3, when you stay like this, maybe after one year it’s finished.

“To stay in motorsport, it’s necessary to give opportunities to young drivers, this is the priority. To have a good organisation, good engineers, good mechanics. Mistakes are normal for everybody. What is important is that the people work together. It’s the work of everybody. My son, my wife, the wife of my son. It is impossible for one person to organise like this.”

But Prema has neither the time nor the inclination to live from past successes.

As Rene Rosin explained to Formula Scout: “Our job is to keep pushing. Every year. Especially when the car is keeping the same, the field is getting closer and closer because you know better the car. Our job is to keep pushing and never rely on the previous year’s result because that’s when you start failing.”