Photos: Roger Gascoigne

Thirty years ago today, Luca Badoer wrapped up the 1992 International Formula 3000 title at his first attempt with a crushing victory, his fourth of the season, in the penultimate round at Nogaro

He infamously failed to score a single point in his subsequent Formula 1 career, which reached its nadir with a romantic but ill-judged and ill-fated cameo for Ferrari in 2009 as he replaced Felipe Massa for two races, 10 years on from his last F1 start.

Now he’s back in the single-seater paddocks, supporting his son Brando in Formula 4. Formula Scout chatted to Badoer about his title-winning F3000 season and his career, both before and after his year-of-years in F1’s primary feeder series.

Luca didn’t start karting until the age of 14, with his father acting as his mechanic, before stepping up to single-seaters once he had reached 18.

“In those years [it was] the normal step. To drive on the track, you needed to have a driving license and to be 18 years old, so that was the only thing to do. It was the same for everybody.”

Despite his later successes in cars, Badoer cites the 1988 Italian 100 International karting finale at Val Vibrata as a highlight of his career. He headed qualifying, but his weekend didn’t go to plan: “I had an accident in the pre-final, so I started last in the final. I made an incredible comeback and won the championship. That was something like a miracle at that time. That was an incredible highlight that everybody still remembers in go-karting.”

After dipping his toe into Italian Formula 3 in 1989, he returned for a full season in 1990 in a MRD Racing-run Ralt RT33.

“We bought [Alex] Zanardi’s car from the year before and we were the only team which drove with an old car. The same problem of money. We buy an old car, in a cheaper team but a good [one], and we did a great job as well.”

With victory in the final round, he moved to the Supercars team for 1991, armed with a new Dallara F391. After a slow start, his season ignited with a mid-season run of four consecutive on-the-road wins, including the Monza Lottery Grand Prix.

“I remember the Monza Lotteria for sure because it was on television as well,” Badoer recalls. “But it was all the season very performing and everything was working very well, everything was perfect at that stage. It was a very good season, but we didn’t win the championship, so good but not fantastic.

“The mechanics made a mistake at Mugello and put one tyre on the front that was not marked. I was disqualified for this, and I lost the championship.”

Badoer finished the year fourth in the standings. Had he kept his Mugello win, he would have been champion.

Despite his F3 form, he was certainly not one of the favourites coming into the 1992 F3000 season against a strong field including British F3 graduates Rubens Barrichello and David Coulthard, as well as returning drivers such as Laurent Aiello, Andrea Montermini and Emanuele Naspetti.

Barrichello joined the splendidly-named Il Barone Rampante team, which came second in 1991 with Alex Zanardi. But as the Brazilian explained to Formula Scout, “the jump from F3 to F3000 at that time was much bigger than today, so basically it was tough to drive that F3000”.

Badoer stepped up with Crypton Engineering, a team that had in the two previous seasons since entering the series scored just once. As was often the case in his career, Badoer’s choice of team was driven by money rather than form.

“I spoke to other teams. It was very expensive with a top team, so we chose Crypton because we had a budget just for that team, but it was a surprise for everybody. The team was working very well and we could get, I think, five pole positions, four or five victories – I don’t remember – and we won the championship one or two races before the end. It was fantastic work from everybody.”

Badoer’s season got off to a solid, if unspectacular start, with points in the first three races at Silverstone, Pau and Barcelona. At Silverstone, engine problems caused him to slip back having been running a comfortable second, while in Pau he calmly nursed his stricken Reynard home after sustaining wing damage in a typically chaotic first lap on the French street circuit.

Impressive results for a rookie but still nothing to give any indication of what was to follow.

Crypton turned up for the next round at Enna-Pergusa in Sicily with its own monoshock front suspension, developed by the Italian team’s in-house engineer, Gianfranco Bieli. Badoer qualified on pole and simply romped away to win by 22s from Naspetti, a four-time winner in the championship the year before.

Another dominant lights-to-flag victory followed at the next round at Hockenheim supporting the German Grand Prix, while at the Nurburgring, Badoer had to settle for second on the grid before calmly outbraking Naspetti for the lead on the second tour and pulling out a comfortable lead.

When did he start to believe that he could challenge for the title? “At the start of the season, no, because we have to put many things together but after three races we did a very good step, a very good job. Everything was running, I started to win the first race, the second, the third and then obviously everybody was thinking to get the final victory.”

Having been caught out slightly by wet qualifying at Spa-Francorchamps, in the race he was chasing Olivier Beretta on lap four when he lost control at Raidillon. He shot across the track, skipping over the gravel trap before slamming backwards into barriers on the right-hand side. The left rear corner was torn off the car but fortunately Badoer escaped with whiplash and heavy chest bruising, and an overnight stay in hospital in Liege.

Badoer remembers little of the crash 30 years later, simply demonstrating the spin with a twisting movement of his hands and a shrug.

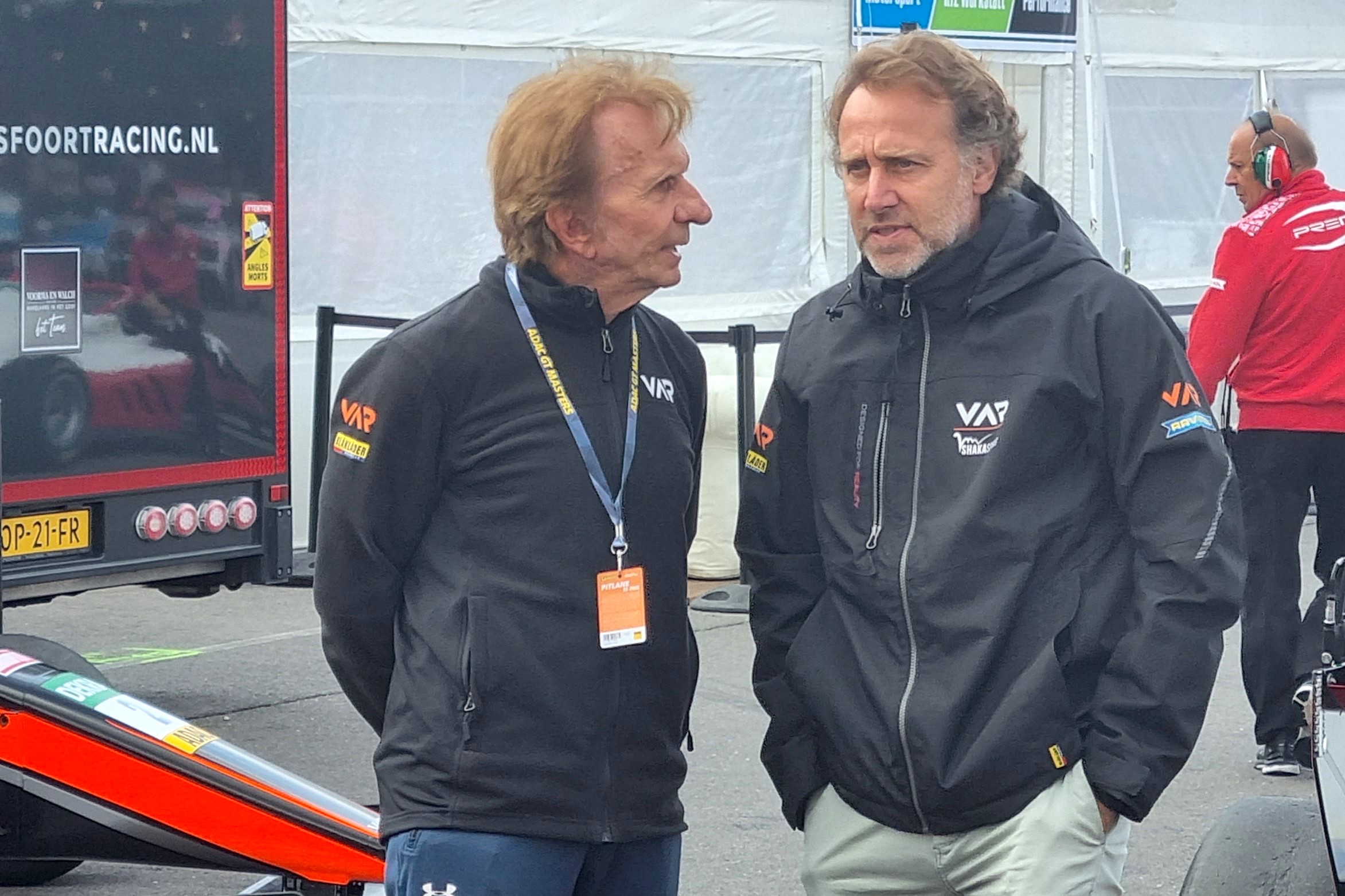

Badoer (r) with fellow racing dad Emerson Fittipaldi in the F4 paddock

Showing no fear, Badoer stormed to pole at Albacete by 0.9s, with second place behind Montermini in the race giving him a six-point lead over his countryman as the teams headed across the Pyrenees to Nogaro for the penultimate round.

In another untouchable performance, Badoer again took pole and drove away from the field at half-a-second per lap. Having built up a comfortable lead of 20s, he took it easy in the closing stages to avoid tripping over backmarkers on the tight Gascon circuit, taking the flag still 12s to the good.

In truth, he had never looked under any threat and the title was his. “We had a big celebration,” he remembers, with a touch of understatement, perhaps.

Badoer does not believe there was any specific reason for his and the team’s dominance. “For sure, it is all together but one of the biggest parts was me, because I got really good confidence with the car,” he tells Formula Scout. “I could push, I could feel to have everything under control, so this was for sure one of the important things.”

He plays down the significance of the team’s monoshock suspension, noting that “sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t.” And to be fair, chassis manufacturer Reynard quickly introduced their own version for all their teams.

Barrichello is not fully convinced though: “They were so much faster than everybody else. When you have something like this, it is definitely something to look at,” he said.

Badoer himself says he doesn’t know what gave him such an advantage that season. “The key to success is to have clever people inside, a good driver for sure and for the victory you need that the team work all together,” he reasons.

“You need very good people inside and in the right places inside the team otherwise it is impossible. It was a surprise because on paper it was not for sure the promising team for the victory, but they did a very good job.”

Barrichello in 1992

Indeed, they did. Before the introduction of single chassis and engine suppliers, there was a colourful mix of chassis – predominantly Reynard but also Lola and Ralt – and engines from Mugen, Judd and Cosworth in F300, unlike today’s uniformity.

Undoubtedly the engine to have, at least on high-speed circuits, was a Heini Mader-prepared Cosworth. But Crypton was not the only team equipped with the preferred Reynard-Cosworth/Mader combination, and Badoer’s team-mate, Michael Bartels, was unable to live with the Italian’s pace.

Barrichello’s Il Barone Rampante team switched to the Mader-tuned engine mid-season. Barrichello explained to Formula Scout that “we had a difficult season because we had the Zytek-Judd engine. The balance of the car was very good, but we lacked on power. And we just said, ‘OK, let’s change,’ and when we changed, we changed the whole balance with the weight distribution and so on.”

While having the right chassis and engine obviously played an important role, there is no doubt that Badoer made the most of it. And, importantly, his rivals acknowledged that he and the team had simply done a better job. “Badoer was superb,” remembers Barrichello. “He was just too far ahead.”

There were plenty of talented drivers in the field, “and in top teams,” Badoer stresses. “It was a big surprise for everybody. And this opened me the door for F1, obviously. It was very important to catch the Formula 1 opportunity.”

Badoer stepped up to F1 with Italian minnows, Scuderia Italia. “I was talking with other teams,” he explains. “I had a very good offer from Tyrrell but finally I chose Scuderia Italia because on paper it was promising [and] because Ferrari pushed to get me there. Philip Morris was the sponsor and together they pushed to get me there.”

At that time, Badoer “didn’t have a contract or a strong relationship with them [Ferrari]. Obviously, they were paying attention to me and, together with Philip Morris, they opened the door for the test [with Scuderia Italia at Estoril in September 1992].”

With hindsight, as he admits, it was “the wrong choice, but this is part of life”. Scuderia Italia’s Lola-Ferrari was disastrously slow, although the Tyrrell-Yamaha was not much better.

If he had his time again, “absolutely, I would sign with Tyrrell. It was a very good contract, a long contract and the Tyrrell was very quick in the years later. It was the best opportunity but finally that was the decision.”

Famously, Badoer failed to score a single point in 50 races in F1, although, in fairness, at a time where only the first six finishers scored points. Running in fourth with Minardi at the Nurburgring in 1999, it finally looked like his luck had changed.

“That race was dry/wet, wet/dry, we had the right situation. I was out always with the dry tyres and it was possible for me at some point [to get on] the podium, but then we broke the gearbox. I was, I think, fourth and had to stop two or three laps before the end.”

In fact, he retired 13 laps from the flag, but the heartbreak was tangible, particularly when team-mate Marc Gene inherited sixth and the final point.

Recalled from the test track to the Ferrari race seat in 2009 after Felipe Massa’s accident in Hungary, Badoer was clearly not race-fit and was hopelessly off the pace. Does he regret coming back? “It was the wrong time because the car wasn’t good that year, and testing was forbidden. After one year without driving, I just went to the race and obviously it was not a good experience but, I mean, it was an experience. Anyway, I drove in a race with Ferrari [which] is something special but it happened not in the right moment.”

He first got involved with Ferrari “in ’98 after some years with Scuderia Italia, two years with Minardi. That was a good team, a good relationship,” he says. “Gian Carlo [Minardi] is a fantastic person.”

Photo: ACI Sport

“I was signing again with Minardi for 1998 but then I had the opportunity with Ferrari, so I spoke with Gian Carlo and I decided to take the Ferrari chance. Then finally, I was a Minardi driver and a Ferrari test driver. Anyway, it was important to stay in the circus.

“It was a fantastic period. It was very important to be part of Ferrari, especially in that period. Finally, I have my satisfaction for the career anyway for that period.”

His vital but unheralded role, in a bygone age of unlimited testing, involved pounding round Ferrari’s test track at Fiorano. “I remember that I did [a total of] 130,000km of testing,” including “34,000km in a single year”.

“It was very good there because I had the opportunity to drive a lot, to develop the best car, and to learn from the team, from the engineer. It was a fantastic opportunity with fantastic results,” he explains. His work undoubtedly made a huge contribution to Maranello’s dominance of F1 from 2000 to 2004.

During that time he built “a very strong relationship with Michael Schumacher, both on track and out of the track. We had the same thinking for the development of the car on track and we were very good friends also off track,” he says.

Had he got a decent result with a smaller team, could it have opened the door with a top F1 team? “It [might have done] but in F1 you don’t have a lot of opportunity,” he replies. “You have to enter in the right door straightaway. If you don’t have the right position straightaway, it’s very difficult to step in the future because there are always new drivers arriving.

“If you drive for a small or medium team it is very difficult to get into a top team if you don’t have already a contract or somebody who is watching you.”

He now maintains a careful watch over son Brando’s career, although he prefers to keep himself to himself at the back of the garage. “In 30 years, obviously a lot of things have changed. I try to give him some information, but I won’t push, as I want him to get the basic experience without too much suggesting or too much teaching,” he says.

Badoer junior was selected to participate in September’s Scouting Camp organised by the Italian Automobile Federation and the Ferrari Driver Academy, but Badoer insists there is no extra pressure or favouritism from his former employers. “I don’t have a contract or a job there [at Ferrari]. I don’t want to push,” he points out. “I don’t want that because I was in Ferrari, he must be in Ferrari. There are other opportunities, we will see.”

The logos of Badoer’s 1992 sponsor, Replay Jeans, on Brando’s F4 car provide a nostalgic connection to his own racing days. He may never have got the career breaks in F1, or at least not until it was far too late, but his achievements in F3 and F2, on a shoestring budget, deserve the greatest respect.

For one summer, 30 years ago, Badoer had simply been imperious as he romped from victory to victory against the top juniors racing in Europe.

Photo: ACI Sport