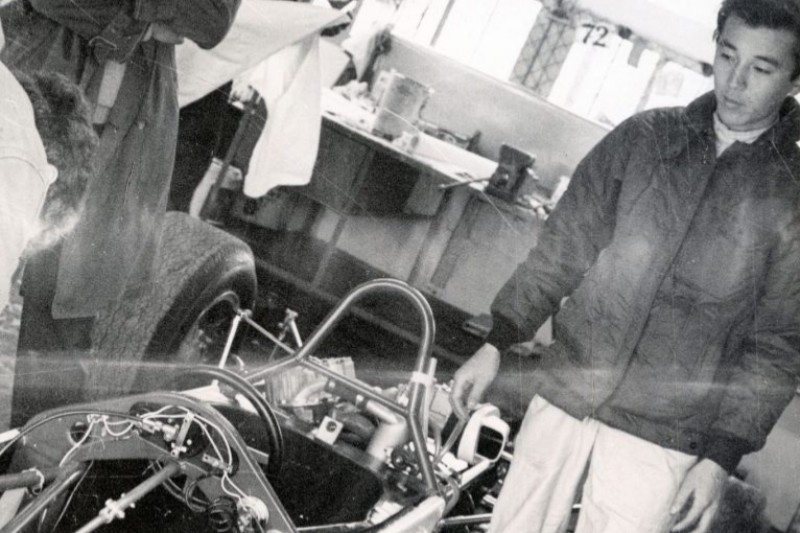

Photo: All-Japan Formula 3000

The probability that Yuki Tsunoda will race in F1 next season, or even in 2022, is sky-high. He’s backed by Red Bull and Honda, but manufacturer support doesn’t guarantee a seat. Just ask these fellow Japanese talents

At 20 years of age, Yuki Tsunoda has rocketed up the European single-seater ladder: In 2018 he dominated the FIA’s Japanese Formula 4 championship in his second full season of competition, but then jumped straight over to the FIA Formula 3 Championship in 2019 and massively outperformed the potential of a struggling Jenzer Motorsport squad – taking a win at Monza and all 67 of the team’s points for the season. At the same time, he was starring for Motopark in Euroformula.

And in 2020, of course, Tsunoda has been a revelation for Carlin, in amongst Formula 2’s strong rookie class: two victories, two poles, third in the standings with two rounds to go. He originally needed a top-four position to secure an FIA superlicense for Formula 1, although the requirements have been relaxed going into 2021 amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

He’s already privately tested for AlphaTauri, will do so again, and in all likelihood will partner Pierre Gasly at the team next year. If and when that happens, Tsunoda will be the 18th Japanese driver to enter a F1 world championship race.

Hiroshi Fushida was the first to make an attempt in 1975. Noritake Takahara, Masami Kuwashima, Masahiro Hasemi, and Kazuyoshi Hoshino were the local heroes on the grid for the famous 1976 Japanese Grand Prix at Fuji Speedway, and Kunimitsu Takahashi joined for the 1977 race. But it wasn’t until Satoru Nakajima debuted in 1987 that Japan had its first full-time F1 driver, making him a national racing hero.

Aguri Suzuki became Japan’s first F1 podium finisher, on home soil too, later to be joined by Takuma Sato and Kamui Kobayashi in the 21st century. Ukyo Katayama became the most experienced Japanese driver through the 1990s, but Naoki Hattori, Toshio Suzuki, Hideki Noda and Taki Inoue suffered much shorter and far less prosperous tenures in F1. In the late ‘90s, Nakajima protege Toranosuke Takagi and Shinji Nakano each showed flashes of brilliance, but neither stuck around.

The 2000s gave us Sato, Kobayashi and Kazuki Nakajima, the first second-generation Japanese driver in F1, but it also gave us Yuji Ide and Sakon Yamamoto.

The 2000s gave us Sato, Kobayashi and Kazuki Nakajima, the first second-generation Japanese driver in F1, but it also gave us Yuji Ide and Sakon Yamamoto.

Being able to race in F1 at all was a terrific accomplishment for all of these drivers, no matter what their results were. Recently Honda has sent many young drivers to Europe, and they haven’t reached F1: Nobuharu Matsushita has won many races in F2, Nirei Fukuzumi and Tadasuke Makino got to F2 too but couldn’t stay, Teppei Natori won in Euroformula, and what will the future hold for 2020 French F4 dominators Ayumu Iwasa and Ren Sato once Honda leaves F1 again at the end of 2021?

And while there was no racing abroad, two-time Super Formula champion Naoki Yamamoto was courted by Red Bull last year too.

Toyota’s F1 withdrawal at the end of 2009 meant its strong young driver programme academy will likely never send a driver to F1 again. The likes of current factory drivers Ryo Hirakawa, Kenta Yamashita, Sho Tsuboi, and Ritomo Miyata (and even Franco-Argentinian SF signing Sacha Fenestraz) all have the talent to be F2 frontrunners with a legitimate shot at an F1 seat.

Of all the Japanese drivers that never got to race in the pinnacle of single-seaters, but certainly had a legitimate chance of doing so at the peak of their abilities, who were the ones that demonstrated most what F1 was missing out on?

From the start of post-war Japanese motorsport all the way through to the 2010s, these are 10 of the best who didn’t make it:

Tetsu Ikuzawa 「生沢徹」

Ikuzawa was a national racing trailblazer. When he quit his factory racing contract with Prince Motor Company, and headed to the United Kingdom to race in the 1966 British F3 Championship, Ikuzawa became the first Japanese driver to race full-time in a European championship. He spent his first two seasons with Stirling Moss’ Motor Racing Stables, and picked up his first three wins in club races in 1967. Frank Williams hired Ikuzawa for ’68 and he enjoyed a breakthrough season with four wins taking him to fourth in the standings.

Ikuzawa was a national racing trailblazer. When he quit his factory racing contract with Prince Motor Company, and headed to the United Kingdom to race in the 1966 British F3 Championship, Ikuzawa became the first Japanese driver to race full-time in a European championship. He spent his first two seasons with Stirling Moss’ Motor Racing Stables, and picked up his first three wins in club races in 1967. Frank Williams hired Ikuzawa for ’68 and he enjoyed a breakthrough season with four wins taking him to fourth in the standings.

In 1970, Ikuzawa made the step up to F2 as a privateer, and in just his second European championship race at Hockenheim he came 0.3 seconds away from beating Clay Regazzoni to victory. It should have been the start of a journey that would make him the first Japanese driver in F1, but without the resources to match the more established European teams, it was high water for Ikuzawa. A move to Group Racing Developments in ‘72 had him sinking down the field, and he made the difficult decision to call time on his F1 racing ambitions in 1973, finishing his full-time driving career in Japan. By then, Ikuzawa had a young successor who was on a path to achieve what he came just short of accomplishing.

Hiroshi Kazato 「風戸裕」

Breaking into motorsport as a teenager, Hiroshi Kazato quickly grew to become one of Japan’s very best drivers in the early 1970s. After rapid domestic success in his privately-owned Porsche 910 and 908, Kazato made the brave leap to America to race in the Can-Am Series, and put in a strong account of himself as a 22-year-old rookie in a Carl Haas Lola-Chevrolet.

Breaking into motorsport as a teenager, Hiroshi Kazato quickly grew to become one of Japan’s very best drivers in the early 1970s. After rapid domestic success in his privately-owned Porsche 910 and 908, Kazato made the brave leap to America to race in the Can-Am Series, and put in a strong account of himself as a 22-year-old rookie in a Carl Haas Lola-Chevrolet.

He came close to signing for the factory March team to race in European F2 in 1972, before being outbid by a young Austrian driver called Niki Lauda. Instead, Kazato raced a privateer March for Peter Bloore in ‘72, then became team-mates with his hero Ikuzawa in ‘73 for GRD Team Nippon – where Kazato regularly outperformed his more experienced countryman.

Kazato’s European F2 breakthrough came at Hockenheim in 1973, where he finished sixth. Two rounds later he was classified fifth at the iconic Monza Lottery Grand Prix, and he ended the season 23rd in the points.

For 1974, Kazato signed a contract with Chevron to drive for its works team as the second driver to James Hunt. But before he could ever make his debut with the team, Kazato’s life was tragically cut short in his last race before returning to Europe.

Kazato and veteran driver Seiichi Suzuki were killed in a multi-car accident in a sportscar in the Fuji Grand Champion Series (Fuji GCS). He was just 25 years old. The accident caused Fuji Speedway to permanently close its infamous 30-degree banked corner section. More importantly, one of Japan’s greatest drivers was taken down before he could realise his full potential.

Keiji Matsumoto 「松本恵二」

Hoshino and Nakajima were the Senna and Prost of Super Formula through the late 1970s and early 1980s. If anyone filled the Mansell/Piquet role during that time, as the one man who could consistently threaten their duopoly on the track, it was the smooth-driving, swashbuckling Keiji Matsumoto, who spent 16 seasons in the series as it evolved through F2 and Formula 3000 regulations from 1976 to 1992, winning 11 races and the 1979 title – by just a single point over Hoshino.

Hoshino and Nakajima were the Senna and Prost of Super Formula through the late 1970s and early 1980s. If anyone filled the Mansell/Piquet role during that time, as the one man who could consistently threaten their duopoly on the track, it was the smooth-driving, swashbuckling Keiji Matsumoto, who spent 16 seasons in the series as it evolved through F2 and Formula 3000 regulations from 1976 to 1992, winning 11 races and the 1979 title – by just a single point over Hoshino.

Matsumoto also thwarted Hoshino in a close fight for the 1983 Fuji GCS crown, but then the two joined forces in 1985 to win the infamous rain-blasted Fuji 1000km, making them and the late Akira Hagiwara the first Japanese drivers to win in the World Endurance Championship and at the peak of the Group C era.

Appearing on adverts of all kinds for Japanese tobacco brand Cabin made Matsumoto a popular, marketable (and handsome) superstar at home, but by the time Nakajima was on his way to racing in F1 at the age of 34, Matsumoto was already 38 and beginning his decline in the Super Formula ranks.

Matsumoto’s age was likely why he never received a legitimate offer from a F1 team. When he hung up the helmet at the end of ‘92, he spent his second career mentoring a generation of future superstar drivers – among them, Nakano, Juichi Wakisaka, and Ryo Michigami, were all disciples of ‘Matsumoto-ism’ in the years to come. Keiji Matsumoto passed away in 2015 after a battle with cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), and his presence is still missed to this day.

Hitoshi Ogawa 「小河等」

Photo: Nakai’s Scribble blog

Japanese drivers tend to be stereotyped as borderline reckless chargers, but Hitoshi Ogawa was so consistent and collected, that he became known as the ‘Japanese Prost’ or the ‘Japanese Boutsen’ during his peak years in single-seaters, touring cars, and Group C prototypes.

Within open wheelers, Ogawa spent the early to mid-’80s bouncing between Japanese F3 (now known as Super Formula Lights) and Super Formula, before finally settling into the top tier in 1988, and establishing his reputation for his sweet, cerebral driving ability. Ogawa only ever won once, but his famous victory in the penultimate round of the 1989 season at Suzuka proved to be the difference as he held off American Ross Cheever to take the title by just three points.

Off the back of his success in Japan, Ogawa was reportedly offered a F1 contract by two teams – the struggling Team Lotus, and upstart Minardi. Ogawa’s brief window for an F1 step-up was closed, however, when he couldn’t find the sponsors to secure a drive.

Two years later, on May 24 1992, he was involved in an accident with Andrew Gilbert-Scott in a SF race at Suzuka, which sent both cars plunging into the fence at the first corner. Ogawa died of severe head and neck injuries, aged 36. This came just a month after he took Toyota’s first WEC win at Monza, and a month before he was scheduled to start the Le Mans 24 Hours for the fourth time in his career.

Akihiko Nakaya 「中谷明彦」

Nakaya, still searching for an F1 seat in 2017

Akihiko Nakaya is not alone in being refused his application for an FIA superlicence – a similar fate befell fellow F1 prospect Katsumi Yamamoto, and of course, there’s the infamous tale of Ide’s superlicence being revoked four races into his career. But Nakaya arguably had the skill to at least give a good account of himself for what resources a cash-strapped Brabham F1 Team were preparing for him in 1992.

After all, Nakaya had been Japanese F3 champion in 1988, and won Super Formula’s first race at Autopolis in 1991. Nakaya also supplemented his single-seater successes with several victories in touring cars.

As Brabham were preparing for an uncertain ’92 season, they signed Nakaya to partner Eric van de Poele. But the FIA denied Nakaya’s superlicence application, having thumbed their nose towards Nakaya’s accomplishments in Japan, after showing no such hesitation for his peers such as Nakajima and Suzuki before him.

Nakaya, then 34, went straight back to SF and survived a terrible accident in the Suzuka season opener (just two months before Ogawa’s fatal crash), and arguably this began a freefall for Nakaya at the highest levels of racing. While he won the second tier of the Japanese Touring Car Championship alongside Gilbert-Scott in 1993, and is still semi-active in pro-am sportscar racing even in his 60s, his single-seater career ended after 1994, two years on from having the F1 door slammed shut.

The FIA’s decision looked worse in retrospect upon Giovanna Amati’s failure to qualify for the first three races of the ’92 F1 season after being named Nakaya’s replacement. She was then replaced by a young Damon Hill.

Nakaya is still technically a professional driver, but not a racer, as he’s a full-time automotive journalist who does driving reviews of new cars on his own YouTube channel.

Juichi Wakisaka 「脇阪寿一」

Photo: Toyota Gazoo Racing

If you’ve ever watched Super GT, Japan’s premier sportscar series of the 21st century, you likely know Juichi Wakisaka as a legendary driver – a three-time top-tier champion behind the wheel – and more recently, as a charismatic, expressive, and successful team manager, the series’ equivalent to the Premier League’s Jurgen Klopp or Pep Guardiola.

All of these title, including his 2019 success as manager of Team LeMans, came after he signed with Toyota at the start of the 2001 season. But in fact, it was Honda who gave him his first chance in Super GT’s top GT500 class – and it was Mugen-Honda who gave him his one and only F1 opportunity.

Wakisaka succeeded Pedro de la Rosa as Japanese F3 champion in 1996, and in 1997 he succeeded F1-bound Nakano at Dome Racing with Mugen in SF, under team director Matsumoto.

As a result of this seat, he got a one-off opportunity to test for Dome’s aborted F1 project in ‘96, and it was the Dome-Mugen connection that gave Wakisaka a F1 test driver role with Jordan in 1998.

Wakisaka attended Jordan’s grand launch at the Royal Albert Hall in London, got a handful of in-season tests in the race-winning 198 car, but after the conclusion of the season was dropped and never found his way onto another F1 squad.

He spent the remaining years of his racing career in the top Japanese championships – five victories from eight seasons in SF, and of course, the three Super GT title that led to him being nicknamed ‘Mr Super GT’ by the end of his career in 2015.

Satoshi Motoyama 「本山哲」

Photo: Toyota Gazoo Racing

Only Kazuyoshi Hoshino has ever won more in SF than Satoshi Motoyama, a 27-time race-winner. And only Hoshino and Nakajima have more title than Motoyama’s four. And in 2003, while honouring his late childhood friend and MotoGP rising star Daijiro Kato, Motoyama became only the second driver in history (and presently one of just four) to win the Super GT and SF titles in the same year. But unlike Hoshino and Nakajima, Motoyama never had a chance to race in F1 during his career peak.

His 2003 success led him to an in-season F1 test appearance with Jordan on the eve of the Japanese GP at Suzuka, where he was within a second of incumbent Ralph Firman in the one and only time he’d ever drive the team’s EJ13 car in anger.

Two months later he joined Renault for post-season testing at Jerez, a convenient tie-up with Motoyama as the star factory driver for Nissan in Super GT and a representative of the manufacturer since 1996, and Nissan being part of the same automotive group as Renault.

His laptimes were modest in comparison to Renault’s star driver Fernando Alonso, though there was room for improvement. But with Alonso as the centrepiece of the team and Jarno Trulli still as swift and experienced as ever at that point, Renault had no room for a prospective 32-year-old rookie on their team. And with no ties to Nissan’s Japanese rivals, or deep pockets to buy his way into a Jordan or Minardi seat, Motoyama never again pursued a F1 seat after the winter of 2003.

Success in single-seaters continued though, with the fourth of his SF titles coming in 2005 and still winning in the series in 2007. He remained a Super GT frontrunner until the end of 2018, when Nissan dropped the 47-year-old from its line-up.

That came as a shock within motorsport even beyond Japan’s borders, such was the longevity of Motoyama’s success, but he was promptly signed up as executive advisor of NISMO, Nissan’s motorsport division, and is team principal of B-MAX Racing’s SF programme.

Tsugio Matsuda「松田次生」

Photo: Toyota Gazoo Racing

In 1997, three drivers graduated with formula racing scholarships from the Suzuka Circuit Racing School. One was Takuma Sato. One was Toshihiro Kaneishi, who became the only Japanese to win the German F3 title in 2001. The third was 18-year-old Tsugio Matsuda, a local driver and a CIK-FIA Asia-Pacific Karting champion.

Days after his 19th birthday in 1998, he scored points on his SF debut at Suzuka. He raced in Japanese F3 full-time though, and didn’t genuinely step up to SF until 2000. In just his fourth career start, he took his first win at Mine Circuit driving for Satoru Nakajima’s team.

Then Matsuda went on a spell of five seasons without a SF win, but built up momentum as a factory Honda driver in Super GT, narrowly missing out on the 2002 title.

In 2005, Matsuda, now 26, was still one of Honda’s top talents – and off-season rumours suggested that he might be on his way to its F1 programme as a test driver, or to race in GP2 with Honda’s support. Instead, he departed Honda and signed to rival manufacturer Nissan for 2006.

In time, he set the record for the most Super GT wins, with his two titles in 2014 and ’15, and 17 of his 22 victories coming at the wheel of a Nissan. And his SF form did eventually arrive, as he claimed back-to-back titles in 2007 and ’08. But in a downward-spiralling economy and with few vacancies on the grid, Matsuda would never find his way into F1 despite his incredible skill.

Keisuke Kunimoto 「国本京佑」

Photo: Toyota Gazoo Racing

Only two Japanese drivers have ever won the Macau Grand Prix: Sato in 2001, and Keisuke Kunimoto in 2008. The latter’s was a milestone victory that followed up being Japanese F3 title runner-up to TOM’S team-mate Carlo van Dam and becoming the youngest ever Super GT300 race-winner, and winning the ultra-competitive Formula Challenge Japan title (the predecessor to Japanese F4) the year before.

As a Toyota junior, Kunimoto was seemingly on the fast track to following Kazuki Nakajima and Kamui Kobayashi to F1.

But just four years later, he had quietly retired from motorsport at the age of 23.

Kunimoto, of Korean descent, was set to be called up by the Carlin-run Team Korea to race in A1GP’s visit to Kyalami in South Africa in February 2009, but a shipping issue prevented his car from being in a condition to be raced.

He did a find a seat in a depleted SF field with Team LeMans that year, but struggled for results as a rookie and finished 13th and last in the standings. After that failure he contested the final two rounds of the Formula Renault 3.5 season and also languished down the field.

By 2010, Toyota was out of F1, and Kunimoto had acrimoniously parted ways with the manufacturer in the off-season.

Instead of accepting a drive in a domestic series, Kunimoto committed to remaining in Europe. The Epsilon Euskadi team that had given him his FR3.5 debut signed him for the full 2010 season, but he only made the points once. And by 2011, with no factory backing, no private sponsors – and no opportunities waiting in Europe or back home in Japanm he had fallen off the radar as quickly as he came on the scene.

His younger brother Yuji has had far more success at the higher levels. After winning the 2010 Japanese F3 title, he’s established a lengthy career in Super GT, won the 2016 SF title and is an outside bet for winning a second this year.

Toru Takahashi 「高橋徹」

Far too many young drivers were killed before they could make an impact in Japanese motorsport, but Toru Takahashi’s all-too-brief career showed enough promise that his peers believed he could have succeeded in F1.

He was 18 when he made his racing debut in 1979. By 1982, he was a title contender in SF, then run to F2 regulations, even outperforming team-mate Aguri Suzuki. It was a Fuji GCS test late that year that caught the attention of Hiroshi Tanaka, owner of SF’s top team Heroes Racing. And with Tanaka’s star driver Hoshino leaving the team to start his own squad, Tanaka made 22-year-old Takahashi his new number one driver for 1983.

In his very first SF race at Suzuka, Takahashi finished second behind reigning champion Nakajima. He qualified on pole position in just his fourth race. With how quickly Takahashi had achieved success, an F1 opportunity surely would have come to him in the near future.

Sadly, on October 23 1983, Toru Takahashi lost his life in the Fuji GCS season finale when his car spun out, went airborne and was crushed against the catch fencing. The crash also killed a spectator and injured three more. There’s no telling what Takahashi would have accomplished in the years to come, and his shortened SF season still resulted in fifth in the points, but like Kazato and too many others before and after his time, fate dealt a fatal blow to his aspirations of future success.