The inaugural FIA Motorsport Games Formula 4 Cup took place last weekend. Had a similar event taken place half a century ago in 1969, who would have entered, and what would they have driven?

Motorsport appeared at the Olympic Games in 1900 as a demonstration event, and it took 118 years before it appeared again in an International Olympic Committee-organised event. Three of motorsport’s global governing bodies were recognised by the IOC a few years prior, and one of them has now taken the steps to organise a Olympics-rivalling event of its own.

While the Olympic Charter still bans motorised events, the advance of technology has undeniably accelerated athletic progress in multiple Olympic events, especially when marginal gains are involved, and just like motorsport it makes it difficult to compare the achievements of different eras.

Unless the Motorsport Games keeps the exact same cars in use for each category going forward, and therefore meaning the required skills remain the same, then such comparisons will also be too difficult to make. The FIA and event promoter SRO is already planning to expand the Games, including more single-seater events, and there will inevitably new cars down the line.

With that in mind, it’s fun to hypothesise what the junior single-seater element would have looked like had the Motorsport Games existed 50 years ago, at the end of the 1960s.

Formula Ford was in its infancy at the time, and already had a variety of active manufacturers, but Formula 3 was the more globally recognised category and so it is Formula Scout’s pick for the hypothetical 1969 Motorsport Games.

Formula E racing around Beijing Olympic Park in 2014

Most modern Olympic venues have gone on to become circuits, and given London has been a host of the Summer Games on three occasions, it is the ideal pick for a historic Motorsport Games. Crystal Palace held races from the 1930s through to the 1970s, and hosted everything from Formula 1 to the British Touring Car Championship.

The track-side banking was ideal for spectating, and fans got to see the theatrics of the infamous F3 battle between James Hunt and Dave Morgan in 1970.

Hunt is one of the 20 drivers, all stars in F3 or FFord at the time and representing individual nations, that Formula Scout has picked to contest the 1969 games. Who do you think would be the winner?

Key: Standard text shows achievements prior to 1969. Bold text shows future racing results.

Tim Schenken AUSTRALIA

1968 BRSCC British F3 champion, 2nd in 1969 European F3 Cup 14th in 1971 F1, 19th in 1972 F1, 4th in ’71 European F2

After racing karts, touring cars and Formula Junior in his home country, Tim Schenken boarded a boat and searched for a motorsport career in Britain like many of his contemporaries.

His few races in 1967 set a good impression, and for ’68 he was given a brand new Merlyn chassis to race in FFord. So dominant he was, he then got a call from Chevron to race in British F3 – usually on the same weekends – and won both titles.

Schenken became a factory Brabham driver in ’69, but results were harder to come by in a varied campaign across Europe. He was the French Craven champion, and won at Crystal Palace, but was only sixth in BRSCC British F3.

A step up to European Formula 2 resulted in fourth place in his second season, enough to earn seats in F1 with Frank Williams, Jack Brabham and John Surtees. In Austria he became the first Australian to take an F1 podium, and founded successful manufacturer Tiga Race Cars before retiring and becoming CAMS’ director of racing operations.

Claude Bourgoignie BELGIUM

4th in 1969 European FFord, 1967 BRSCC National FF1600 champion 7th in 1975 European F2, 1970 Belgian F3 champion

As soon as he left his teens, Claude Bourgoignie set about making his name in racing and immediately established himself in the newly created FFord. He won the first ever BRSCC National FF1600 title, a series which in a different iteration is still going on today, and finished fourth in the continental championship two years later.

After winning the 1970 Belgian F3 title, Bourgoignie got a works-backed Lotus drive in British F3. There were no wins, but Bourgoignie still stepped up to F2. It took several seasons for him to make an impact, and he moved on to touring cars.

Emerson Fittipaldi BRAZIL

Emerson Fittipaldi BRAZIL

1969 BRSCC British F3 champion 1972 & ’74 F1 world champion, 1989 CART champion, 1971 & ’72 Brazilian F2 champion

Brazil had a strong junior single-seater scene in the 1960s, meaning future F1 and CART champion Emerson Fittipaldi was well prepared for his move to Britain in 1969. It took just a few races in FFord for the Jim Russell Racing Driver School (JRRDS) to be convinced to take in Fittipaldi for British F3, and he won the title in style.

Fittipaldi also starred in Europe driving FFord cars that year, and when he returned home also won a FFord title.

Team Lotus was eager to get its hands on Fittipaldi, and signed him up for F1 straightaway. He won one grand prix in his rookie season, just a year after starring in F3, and by 1972 was world champion.

Vladimir Hubacek?CZECHOSLOVAKIA

1969 Czechoslovakian F3 champion, ’69 F3 Cup of Peace and Friendship of Socialist States winner 1970 Czech F3 champion

Famed more for his rallying accomplishments driving Alpines, Vladimir Huback picked up some important skills in circuit racing and one of the cars he drove in F3 is now a museum piece.

Driving a Lotus 41, Hubacek was usually the class of the field in the Czechoslovakian championship, but he wasn’t on top of the podium when races took place with drivers from further afield. Admittedly, they often had better prepared machinery.

He also won the single-seater championship for all of the countries in the ‘East’ of Europe, which included races in what is now Belarus, East Germany and Poland. He retained his Czech F3 crown in 1970, before focusing on rallying again.

Frieder Raedlein?EAST GERMANY

1969 East German F3 champion, 2nd in 1960, ’63, ’66 & ’67 East German F3

F3 began as a 500cc formula in the 1940s, and extended quickly across Europe. The exploits of those in Eastern Europe are all but ignored in history, but one of those who saw the evolution of the category from the driving seat was Frieder Raedlein.

He drove in the 500cc cars in East Germany, then the more powerful FJunior chassis once they had gone out of fashion. It was at this point that he started winning races, and success was even more regular once the championship switched to the F3 regulations that evolved over the decades and were in use until this year.

It took 10 attempts, but former Mercedes-Benz apprentice Frieder finally won the title in 1969 in a dramatic season finale, having been runner-up four times prior.

Francois Mazet?FRANCE

1969 French F3 champion 32nd in 1971 F1, 9th in 1970 Limborg GP, 20th in ’71 European F2

A great friend of Jo Siffert, Francois Mazet career was defined by the strength of his opposition. He beat a future rallying star to get his first break in F3, then bettered a field that included Le Mans 24 Hours winner Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, European F2 champions and F1 race-winners Jean-Pierre Jabouille, Patrick Depailler and Jacques Laffite to win the 1969 French F3 title.

A graduation to F2 immediately after proved unsuccessful, even when he joined Siffert’s team. Siffert trusted Mazet’s talent, and handed him his F1 debut at the 1971 French GP. He qualified a distant last and finished a lapped 13th.

When Siffert died later that year, Mazet lost his love of racing and a combination of factors led to him quitting racing. He returned to F1 a decade later in a sponsorship role, as well as reportedly getting involved in lemon farming.

James Hunt GREAT BRITAIN

James Hunt GREAT BRITAIN

15th in 1969 BRSCC British F3, 6th in ’69 European FFord 1976 F1 world champion, 4th in 1975 F1, ’76 & ’77 RoC winner

Everything that James Hunt is famed for was evident in his junior career, which technically started in Mini racing. Success was hard to find in FFord, but he raced in the category for well over a season before finding enough cash to step up to F3.

He finished eighth on his British championship debut at Mallory Park in 1969, and was on the podium a race later. Two wins came in club races, and he potentially could have won more had he raced the full season. He remained in F3 for 1970 and ’71, but there were not enough wins to suggest “Hunt the Shunt” would one day be F1 world champion.

Once Hunt joined Hesketh Racing in F2, the picture looked a little different and their historic relationship continued into F1.

John MacDonald?HONG KONG

1965 Macau GP winner 1970, ’71, ’73, ’74 & ’75 Malaysian GP winner, 1972, ’73 & ’75 Macau GP winner

Now considered a part of China, Hong Kong was a British colony in the 1960s and many of its racers were British citizens.

John MacDonald was one of a selection of drivers that monopolised the top step of the podium in junior single-seaters in the area, with a Macau Grand Prix victory already on his CV by 1969.

His trophy haul really kicked off in the 1970s, winning Macau a record four times and the Malaysian GP on five occasions. When he wasn’t winning he was usually on the podium, and his winning cars usually went on to be raced by drivers wanting to emulate his success.

Hong Kong was represented in the 2019 Motorsport Games by Hugo Hong, while the F4 cars are supplied by local brand KCMG.

Sverrir Thoroddsson?ICELAND

1964 SMRC British F3 champion, 9th in 1969 European F3 Cup, 9th in ’69 Knutstorp Cup 21st in 1970 MCD British F3

Before he commentated on F1 for Icelandic TV and worked in aeronautics, Sverrir Thoroddsson was Iceland’s leading motorsport hope.

While his home country is not famed for its single-seater exploits, Thoroddsson impressed early on by winning the Scottish Motor Racing Club-organised F3 championship title in 1964, and was third in the F3 classification of the Vanwall Trophy.

It took two years before his name was in the headlines again, when he missed out on victory in the iconic Monza Lottery GP for F3 cars by just two tenths of a second. He continued racing in the category when he could, being classified ninth in the Sweden-located European F3 Cup in 1969, and then tackling the British F3 season with the JRRDS a year later.

JRRDS had been the same team that had helped him when he first came to race in Britain six years prior.

Hengkie Irawan?INDONESIA

Hengkie Irawan?INDONESIA

1968 Malaysian GP winner, ’68 Shah Alam GP winner, 2nd in ’68 Macau GP?5th in 1970 Singapore GP

Like Hunt, Hengkei Irawan started racing in Minis before trying his hand at junior single-seaters. Racing mostly in Malaysia, he slowly brought himself up to the standard where he was able to compete for the major grand prix titles in Asia.

Crashing out of the lead of a club race in Malaysia put his preparations for the 1968 Macau GP on the backfoot given he was set to use the same Elfin 600 car, but he repaired it in time to race and ended up only finishing a few seconds short of victory – back when the grand prix was over two hours long.

He did win the Malaysian GP that year, admittedly after leader Max Stewart had to pit for fuel, but he was never able to repeat that feat in the years after. Motorsport’s popularity in Indonesia, especially karting, has been credited to Irawan.

Brendan McInerney IRELAND

27th in 1969 BRSCC British F3 20th in 1971 BRSCC British F3, 21st in 1970 MCD British F3, 29th in 1974 European F5000

Like many drivers of the time, Brendan McInerney set up his own team to further his racing interests. It was called Race Cars International and propelled him to some healthy results in sportscars after a long time spent in F3.

In 1972, he was partnered with Hunt in the factory March team, but the operation was panned from all sides and McInerney left mid-season after a best finish of 17th. He was unhappy with the car and how the team was run under future FIA president Max Mosley, but his previous F3 form was nothing to shout about anyway.

After his March disappointment, McInerney stepped up to European F2 and took one top 10 finish before moving on to Formula 5000 for just over a year before calling time on his racing career.

Gian Luigi Picchi ITALY

1969 Italian F3 champion, 6th in 1968 Italian F3, ’68 Italian F850 champion 3rd in 1970 Italian F3, 2nd in 1971 ETCC

After winning karting titles at a national and continental level, Picchi raced in the entry level single-seater categories of Italy. On the way to the 1968 Formula 850 title, he made his first appearances in F3 and immediately made an impact.

Picchi convincingly won the 1969 Italian F3 title as lead driver for Tecno, beating future F1 driver Vittorio Brambilla and Claudio Francisci – who continued winning in Italian F3 until 1973 and was a champion in prototypes over 40 years later.

A part-time return to F3 in 1970 resulted in more wins for Picchi, but after going fastest in driver shootout organised by Alfa Romeo, his career leaned towards racing touring cars for the manufacturer before becoming a father changed his priorities.

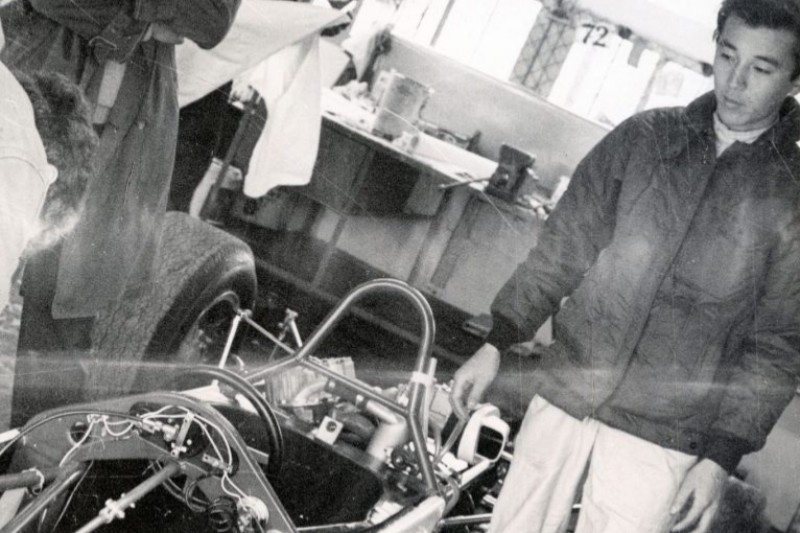

Tetsu Ikuzawa?JAPAN

Tetsu Ikuzawa?JAPAN

1968 Martini F3 Trophy winner, 4th in ’68 British F3 5th in 1974 Super Formula, 8th in 1970 European F2

From a young age, Tetsu Ikuzawa wanted to design cars. He was raised by an artist and went to art school, where he did end up designing a vehicle. Cars were scarce in post-war Japan, and there were only hillclimbs available to learn car control.

Suzuka’s creation was embraced, and sometimes Ikuzawa enlisted future Mugen founder Hirotoshi Honda to be his mechanic.

His single-seater career started with Motor Racing Stables in Britain, and his approach and performances turned heads. After a few races in 1966, Ikuzawa was a strong ninth in the ’67 British F3 standings, and won four club races. Frank Williams hired Ikuzawa for ’68 and he took fourth in the standings, before expanding to Europe in ’69.

The 1970s were spent in F2, finishing eighth in his rookie European campaign but failing to match that on subsequent attempts and therefore missing out on F1. He returned to Japan and won titles as a Super Formula team boss.

Howden Ganley?NEW ZEALAND

3rd in 1969 European F3 Cup, 17th in ’69 BRSCC British F3 13th in 1972 F1, 15th in 1971 F1, 2nd in 1970 European F5000

Co-founding Tiga with Tim Schenken and being the third-ever employee of McLaren is what Howden Ganley is known for, but he too had a career of his own in the driving seat (as well as being a motorsport journalist).

At first this involved racing a Lotus Eleven on home soil, before he emigrated to Britain in the early 1960s and found work as a mechanic. He paid his way into a few FJunior races before sponsorship dried up, then joined startup company McLaren.

Almost immediately after McLaren made it to F1, Ganley resigned. Their paths continued to cross and in his new job he earned enough money to buy a F3 car and returning to racing in 1967. His results continually improved over ’67 and ’68, and the purchase of a new car for ’69 meant his fortunes improved further.

Former employer McLaren offered Ganley a test in 1970, then helped a European F5000 campaign to warm-up for F1. Bruce McLaren’s tragic death meant Ganley never took his F1 seat, but he still raced at the top of the sport.

Jan Bussell?SINGAPORE

1968 Macau GP winner, 3rd in 1960 Macau GP 1971 Macau GP winner

Another whose domicile status in the Far East enabled him to represent his adopted nation, Jan Bussell was an infrequent rival of MacDonald throughout the 1960s. Singapore was, however, still a Malaysian state when Bussell first raced.

Beating Irawan to victory in the 1968 Macau GP was to be expected given Bussell’s far more powerful car, but he was mostly on the other side of the equation when it came to his second win in 1971 with his modified McLaren M4C. His victory margin then was close to a minute.

Bussell continued racing through the 1970s, and is not to be confused with the man who helped create Muffin the Mule.

New Zealand’s Howden Ganley with Bruce McLaren

Enn Griffel?SOVIET UNION

1968 & ’69 Soviet Union F3 champion, 1963 Soviet FJunior champion 1971 Soviet F3 champion, ’71 Estonian F3 champion

While Estonian through and through, Enn Griffel would have only been able to represent the Soviet Union in an Olympic-style event in the 1960s.

His name first became known in Soviet racing circles when he won the 1963 Soviet Formula Junior championship, and he started being one of the drivers pushing the development of the Estonia racing car manufacturer. Other Soviet countries also produced their own self-branded cars, but it was the Estonias that impressed Western eyes when they finally saw them.

Griffel’s first Soviet F3 title came in 1968, and he took a dominant second title a year later. He had an off year in 1970, then hit back in ’71 with the Soviet and Estonian titles, as well as fourth place in the wider reaching Cup of Peace and Friendship of Socialist States. Locally sourced information suggests Griffel won many more titles in Eastern Europe, and became the star of a short film about this career.

Jorge de Bagration?SPAIN

9th in 1968 Barcelona GP, 20th in ’68 European F2, 1969 Spanish Touring Car champion

The man formally known as Prince Jorge Bagration of Mukhrani was a claimant (or technically head) of the throne of Georgia as well as a racing driver, and would have made it to F1 were it not for some very unusual circumstances.

After racing motorcycles and then a huge variety of cars, Bagration finally tasted single-seaters in the support race for the 1967 Spanish Grand Prix, and on a return to the circuit in 1968 he finished second. He swiftly moved up European F2 the same year, representing his adopted country in a cameo, and was top 20 in the standings despite his inexperience.

At the same time he was winning in touring cars and sportscars, not returning to single-seaters until his attempted F1 debut.

Bagration entered the 1974 Spanish GP with sponsorship from the local team that had ran him in F2, even holding a press event to announce it, but his sponsorship fell through ahead of the weekend. Even worse, the outgoing president of the national motorsport federation lost the entry list while clearing his office, and the replacement didn’t include Bagration’s name. As a result, his royal highness was not allowed to take part in any track activities.

Ronnie Peterson SWEDEN

1969 European F3 Cup winner, 1968 & ’69 Swedish F3 champion 2nd in 1971 & ’78 F1, ’71 European F2 champion

Arguably more impressive than his future F1 results was the fact Ronnie Peterson started his single-seater career in a self-developed Swedish car. The combination was third on its debut in 1966. In his first season of Swedish F3 a year later he was fifth, enough to gain the support of Tecno for 1968.

The result was two Swedish titles in a row, and wins in Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy and Monaco’s F1 support race.

In 1970 he tackled F1, F2 and sportscars with admirable skill; earning him a factory March contract. With that, he became European F2 champion and F1 runner-up in 1971. He spent the next seven years as a professional, while also starring in F2 from time to time, before his untimely death.

Juerg Dubler SWITZERLAND

Juerg Dubler SWITZERLAND

1969 Neubiberg Race winner, 1968 Swiss F3 winner, 1966 Portugual GP winner 1970 Int. Motor Show Cup winner

It’s a travesty that Juerg Dubler never raced in F1, for his junior single-seater trophy haul was massive. He won the 1966 Portuguese GP, the international Czech race twice, the Pasquale Amato Gold Cup, the Coppa API, the Zandvoort Trophy, te Swiss F3 ‘championship’ and the 1969 Neubiberg airport race.

His results weren’t limited to mainland Europe, as he also finished ninth in British F3 in 1970 and 10th in South America’s F3 championship a year later. Motorsport was his passion, and one of his early exploits being taking a road-standard Volkswagen Beetle around the Nordschleife in 13m30s, and he had an ongoing rivalry with Briton John Fenning.

After the F3 regulations changed, Dubler moved on to F2 but the budget hike proved too costly despite his obvious talent, and his only taste of F1 came in a management role.

Roy Pike USA

4th in 1969 BRSCC British F3, 5th in 1966 French Craven F3, 12th in ’66 British F3 9th in 1970 British F5000

Roy Pike was one of America’s most successful races abroad during the 1960s, and he started off by entering F3 races in France. He ramped up the regularity of his on-track appearances, which was still restricted heavily by budget, once he switched his attentions to Britain.

He only managed to enter one championship race in British F3 in 1966, but won it from pole and took fastest lap, and also won the Radio London Trophy at Silverstone that year. The Charles Lucas-prepared Lotus he raced in was quality, but Pike’s own skill to turn up and make the most out of a weekend was impressive.

In 1967 he won at the fearsome Enna-Pergusa, and in his three British F3 appearances took two wins and a pole. Lotus signed him after seeing these performances, but he remained in F3 until 1970, when he stepped up to F5000.