Photos: Jenzer Motorsport & Roger Gascoigne

In its 30th season, Jenzer Motorsport is still proudly independent and family-run, an old-school racing team. Andreas Jenzer and wife Esther are passionate as ever about motorsport, particularly junior single-seaters

Formula Scout had the privilege of following the team through its anniversary season, including a four-race winning streak in mid-summer, and took the chance to sit down with Andreas Jenzer to reflect on the team’s history, some of its drivers and the changing face of motor racing.

When Taylor Barnard crossed the line at Spa-Francorchamps to take a well-deserved FIA Formula 3 victory for the team, its first at that level since Yuki Tsunoda’s sprint race win at Monza in 2019, it would have been hard to imagine a more popular winner in the paddock.

Champagne corks popped, the team hugged each other, and anybody else in the vicinity, and cried with emotion as rival teams were quick to add their congratulations.

Just one week before Spa, Jenzer had told Formula Scout: “For us, the wish is our health keeps going well, that we can keep pushing in motorsport, and obviously to try to bring home some trophies for the team and winning some races in FIA F3 will be really nice.”

Yet, reflecting on the end of the season, Jenzer could still not hide some disappointment that a late safety car had, in his view, prevented Barnard from triumphing again at Monza.

“It’s quite amazing how fast these 30 years went,” he tells Formula Scout. “I don’t think that there are many teams in the paddock [which] never had any big financial trouble, with the same partners, with the same names. Jenzer Motorsport is Esther Lauber, my wife, and myself. We are 50:50 and we run the things ourselves,” he says proudly.

The Jenzers taking podium pics

While many rival teams have brought in external investors, Jenzer has remained “a little bit an old family team”.

“We don’t have any commercial partners. We are pretty proud of this, that we are still here and still in junior championships.

“We had many times the option of going to prototypes or GT cars. I never really had the feeling for having windscreen wipers on a car. It’s always single seaters in my heart, single-seaters is a nice part of my life, I have to say.”

Jenzer himself “started racing with an Audi 50, just doing some wild races where there was no licence needed” at Switzerland’s only circuit, Lignieres, which is just 30km away from the team’s current base in Lyss.

But as soon as he got into a Formula Ford car in 1987, he immediately knew “I was not going to sit back in a car with windscreen wipers. I was really fascinated by and passionate about single-seaters”.

“I was already 23 years old. I was only able to start racing when I was able to earn my own money from my job as an electrician. My parents were never able to support me financially, so I just did a lot of work to finance myself to go racing and I was also lucky this time with Esther, then my girlfriend, to help pushing, first as a driver and then the transition into a race team.”

Running his self-built Faster chassis, developed together with friend, Alain Feuz, Jenzer took consecutive top-three finishes in the Swiss FFord Championship in 1990, ’91 and ’92. The highlight came in the traditional end-of-year trip to Brands Hatch’s FFord Festival in 1992.

“I did pretty well up and should actually have reached the final,” he remembers. Driving his Faster, Jenzer crashed out of his quarter-final whilst running “in a good position”, leaving him too much to do in the semi-final to make up ground.

Jenzer driving in the 1992 FFord Festival

“On the Monday after the Festival I tested a Swift and was incredibly fast. I said: ‘Bloody hell! How easy it is to drive a car from a manufacturer compared to the car I was used to drive’.”

After his promising ’92 season, Jenzer had his heart set on stepping up to Formula 3. “I was 29 years-old and I had my dream of becoming a racing driver. I tested Formula 3000, Porsche Cup, F3 and all these tests went really well.

“I had basically all my money together to do F3. The money from my biggest sponsor [Binggeli Galvano] was the last bit to fill. And then he said to me: ‘If you go F3, I don’t give you any more money. But if you start a racing team, I will give you double the money’.”

Jenzer had already struck a deal to bring two Swift chassis back to Switzerland and when a father turned up looking for a team to run his son, “I was thinking all these things seem to be a sign to really start the team”.

So, within months, Jenzer found himself not only as a FFord team owner but also the official Swift importer for Switzerland, “and already in the first year I sold seven cars!”

Unsurprisingly, “Swift was very happy and the impact of starting a competition team against Van Diemen in Switzerland worked out perfectly”.

So perfectly in fact that Jenzer Motorsport ended its first season with its first silverware, as Hans Pfeuti won the Swiss FF1800 Championship. The team would dominate the series with six titles in eight years.

For Jenzer himself “the plan was not to race anymore in 1993”, but he came out of retirement for a last time to take on future Sauber Formula 1 driver Norberto Fontana, who was making a name for himself in Switzerland and around Europe in a factory Van Diemen.

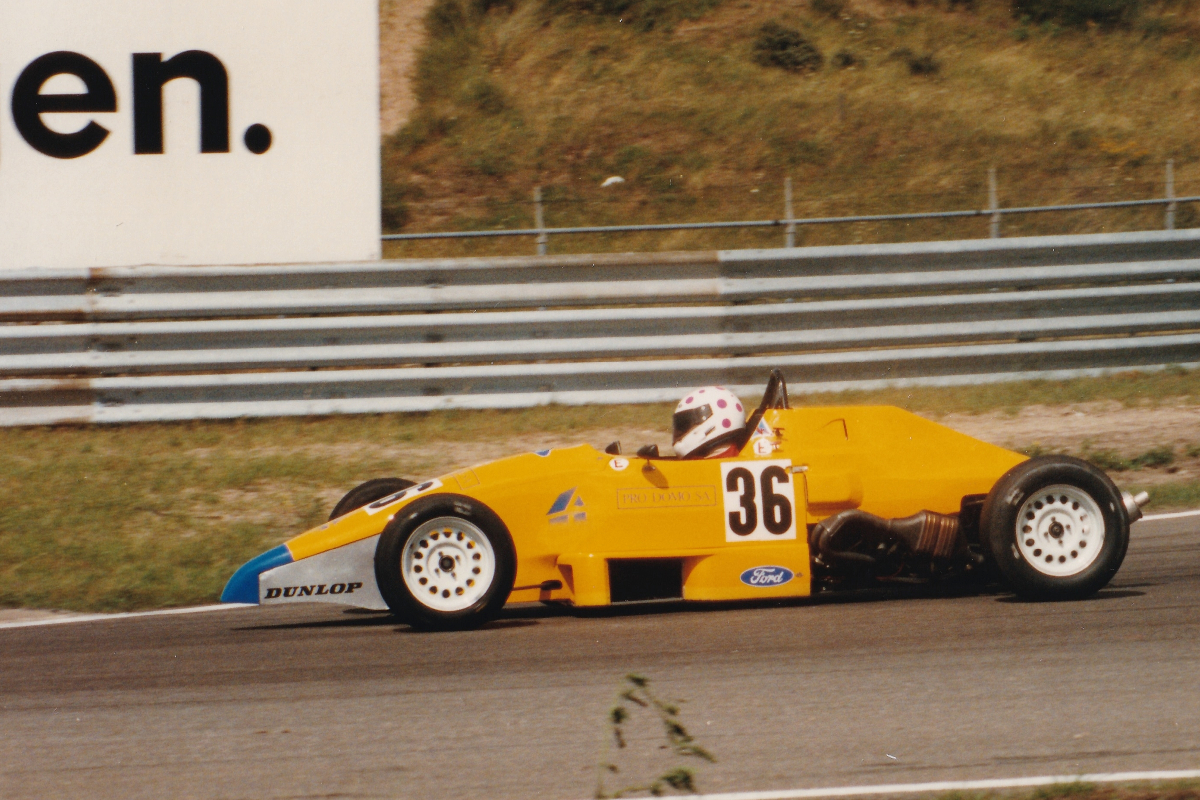

Jenzer driving at Zandvoort in 1993

“Swift was a little bit worried that I will not do the business selling cars, that we can only sell cars if we are winning. But it wasn’t like this,” he remembers.

And by now Jenzer was settling into the role of team owner: “I really have to say already in ’93 I enjoyed looking after the drivers, some who didn’t even have a driving licence on the road. I think my first drivers in 1994-’95 were 16, 17 or 18 [years old].”

“We started racing internationally immediately when we started the team. We went to Germany, to France, we went racing in England, obviously the traditional FFord Festival, which were more an English thing then.

“I still remember some of the set-ups we were running in 1995 in FFord,” says Jenzer. “We had a lot of enjoyment in FFord.

“We had a very good promoter with Gilles Martineau at the time who was promoting the French championship but also looked after the European. We did podiums in the championship in the French, we finished fifth in the Festival in ‘95 with Luciano Crespi in the Swift, second in the European Championship in 1996 [with Iradj Alexander-David] and won the championship in Germany [with Marc Benz in 2000].”

Benz, now working in his family garage in Switzerland, looks back fondly on his time with Jenzer. “It was a really special season,” he tells Formula Scout. “We were travelling almost non-stop to races in Germany, France and the Festival, sleeping in the back of the truck.”

“Andreas believed in me from the start. He was a real father figure. Without him I wouldn’t have been able to step up [from karting]. We worked hard but had a lot of fun. It was a real school of life, both on and off-track” he remembers.

But FFord was already past its heyday, “with the Zetec cars you started to see all the Festivals in 1997 and ‘98 going down to 80 cars [from 100] and the national championships starting to struggle a bit more,” remembers Jenzer.

Jenzer’s history in wins

| Tier | Series | Years | Wins | Podiums | Best champ. pos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | FR V6 Eurocup | 2003-’04 | 6 | 21 | 3rd |

| 3 | FIA F3 Championship | 2019- | 2 | 10 | 6th |

| 3 | GP3 | 2010-’18 | 11 | 26 | 3rd |

| 3 | Int. FMaster | 2007-’09 | 10 | 24 | 2nd |

| 4 | FR2.0 Eurocup | 2001-’09, ’13 | 16 | 45 | 2nd |

| 5 | Italian F4 | 2014- | 16 | 52 | 2nd |

| 5 | F4 CEZ | 2023 | 11 | 29 | 1st |

| 5 | ADAC F4 | 2015-’19, ’21-’22 | 1 | 3 | 3rd |

| 5 | Spanish F4 | 2019-’21 | 5 | 14 | 5th |

And so, when Formula Renault became a spec championship, and “Tatuus came in with a price below €30,000 for a ready-to-race car I immediately jumped on this,” Jenzer recalls.

“I have to say Renault Switzerland was a company with a very strong passion for motorsport. Andre Hefti, one of the guys basically on the board making decisions, was always helping young Swiss drivers like Neel Jani, Marc Benz and Nico Muller and this obviously also helped the team a lot. We got two drivers and we immediately started with FR2.0 [in the] German and European championships.”

“From 2000 onwards we decided to race always outside in the best championships like Italy, Germany or France with FR2.0. Renault with the World Series by Renault did a great championship package, a great organisation, [so] we followed for a long time the Renault world.”

Jenzer Motorsport carried on in FRenault where it had left off in FFord. Benz and Jani were second in the FR2.0 Eurocup in 2001 and ’02 respectively, future DTM champion Bruno Spengler was runner-up in FR2.0 Germany in 2002 with Ryan Sharp going one better the following year.

Red Bull-backed Michael Ammermuller took second spot in the Eurocup in 2005, the start of a longer term relationship with Helmut Marko, before Dani Clos and Pal Varhaug won the 2006 and 2008 Italian FR2.0 series.

In 2003, Jenzer had expanded into the FRV6 Eurocup, which was later succeeded by FR3.5, run under the World Series by Renault umbrella. Success again came quickly with Jani and Sharp narrowly missing out on titles in 2003 and ’04.

Fabio Leimer won the short-lived International Formula Masters championship for Jenzer in 2009, but “there was this GP3 coming and we saw more the way of GP3 because of the Renault support”.

“The first GP3 car had a Renault engine so we were always quite following the Renault situation and we went to GP3 in 2010,” Jenzer explains. GP3 would, of course, metamorphose into FIA F3 in 2019.

“The first GP3 car had a Renault engine so we were always quite following the Renault situation and we went to GP3 in 2010,” Jenzer explains. GP3 would, of course, metamorphose into FIA F3 in 2019.

“The show exploded when the name got changed from GP3 to FIA F3 and the show costs a lot of money. The show has nothing to do with the racing, but investors and drivers want a flash situation.”

Nevertheless, Jenzer appreciates Michel’s efforts “to support the teams in a way that it’s affordable”.

“He’s always looking into the situation that the championship has a financial balance and doesn’t just go through the roof.”

Jenzer is proud of the fact that “ART Grand Prix and Jenzer Motorsport are the two last remaining teams who were there already on day one” of GP3.

At single-seaters’ entry level, Jenzer has been a mainstay of Formula 4 since its inception, stepping across from Formula Abarth to join the inaugural Italian F4 season in 2014, and ADAC F4 in Germany when it launched a year later.

Following the demise of ADAC F4 at the end of 2022, Jenzer added a programme in the F4 Central European Zone championship for this season, with Ethan Ischer edging team-mate Reno Francot for honours at the final round to take Jenzer’s first title in the category since Marcos Siebert beat Mick Schumacher to become 2016 Italian F4 champion.

Jenzer unearthed Siebert in Argentina thanks to the connections of former driver Luciano Crespi, whose 2013 FRenault season was cut short when his sponsor dropped out.

“He was really without money and winning the championship against Mick was a big effort from the team and from a very, very skilled driver,” said Jenzer. With no budget for testing, he reckons Siebert’s total test mileage in three seasons would be “what a Prema driver today is doing before his first race”.

Jenzer Motorsport celebrating F4 CEZ success

A broad smile crosses the face of Siebert, now rebuilding his career in GTs, when approached by Formula Scout for his memories of his time with Jenzer.

“He made me as a racing driver. It was one of the best things that happened to me,” he recalls. “I have really good memories.”

“It was like a second home. Andreas is like my second father in Europe because I grew with them, I lived with them for three years. I was in the workshop making my own car, helping the team, so the reason we won the championship was not only that we were fast, but that we really worked together.”

But a laughing Siebert points out a lesser-known side to Jenzer’s man-management style.

“People that know him know how tough he is with drivers. He’s really strict, especially in the race weekend. He was engineering my car. I learned a lot with him, we had fun, sometimes not that much because he was too hard with me.

“He loves racing, and we were fighting for the championship. When I made a little mistake he was hard with me, banging my helmet sometimes, he was completely crazy. But he knew it was the way to make me faster, so at the end of the day it was the reason why we succeeded.”

Jenzer has maintained his strong Argentinian links, with seven mechanics and one engineer from the nation in his team right now. “They are really passionate people who love motorsport. It’s a nice team with the Argentinian guys here.”

Another non-European to leave his mark was Yuki Tsunoda, who arrived in Europe as the reigning Japanese F4 champion, backed by Honda and Red Bull, and was the first driver announced for the inaugural season of the FIA F3 Championship.

After finishing third in the teams’ championship in GP3 in 2017, Jenzer had suffered a tough season in the final year of the series and concedes that not many teams were clamouring for Tsunoda’s signature.

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

“It was very nice being able to get Yuki at this time, but I think also, there were not too many options for him because all the teams would have probably not jumped on a F4 driver from Japan, who never did a lap in any race tracks in Europe.”

Jenzer remembers when Tsunoda arrived, his lack of physical strength meant he “was not able to hang on to the car for more than five laps”.

“The first step was getting organised with Red Bull and Honda to have him training very hard, seven days a week non-stop from December until he jumped in the car in March.”

Tsunoda’s first acquaintance with car and team actually came in the post-season GP3 test at Abu Dhabi, immediately impressing with his times on each of the three days.

“In the same test there was also another driver testing with Jenzer Motorsport, [Oscar] Piastri, and the two were always on the same level,” Jenzer reveals. “With Piastri it was already organised that he will do FR2.0 Eurocup but Tsunoda was with us.

“We did all the hard work with Yuki, we got a little Japanese boy, not even 50kg heavy, living in Switzerland, organising the things for the boy. We didn’t make a big marketing out of it, what was maybe wrong for us, but I think we did a great work with him, preparing him for Formula 2. We know where he was after a couple of years.

“We worked very hard on this project. That was obviously a huge success for Jenzer Motorsport being part of this success. Obviously, we were expecting that we could continue to have Red Bull drivers but c’est la vie.”

For 2020, Red Bull switched its allegiance to Hitech, which is still its junior single-seater team of choice.

Although Jenzer acknowledges that running cars for Marko was “not an easy task,” they ended up working together for eight or nine years, going back to the team’s time in FR2.0.

Photo: Dom Romney / FIA F3 Championship

“We just had this kind of co-operation at this time. And at one stage the collaboration stopped. Maybe I am a little bit a strong character. I still like to do my own decisions for some of the things and obviously it was nice to work with Red Bull but Red Bull left us and the year after we were with different drivers in front of Red Bull. We were still able to maintain the job.”

Though the team has always been internationally-oriented, Jenzer is naturally proud of the Swiss heritage of the team and has always been a passionate supporter of young Swiss drivers, including Jani, Benz, Leimer, Muller, and Gregoire Saucy.

“We counted last year over 70 Swiss drivers who passed through Jenzer Motorsport. We actually impressed ourselves that we actually had such a big load of young Swiss drivers.”

Running a racing team from Switzerland, one of the most expensive locations in Europe and somewhere with no permanent racing circuit, isn’t easy.

“It’s nice but it involves a bit more organisation and obviously, the financial level is a bit different. We are very exclusive in Switzerland, Jenzer Motorsport together with Sauber in F1 are the two only really established big single-seater teams who also had some good success over the years. Obviously, it’s all about getting organised with things but also when you look how small the country is and still, how many good drivers and how many drivers are coming out of this small country we can be pretty proud of ourselves.”

The relationship with Sauber, at least when Peter Sauber was still at the helm, was a strong one, with Sauber offering his countryman any support needed, “except for money!”.

And being based in Switzerland does have one practical logistical benefit: “We are in the centre of Europe. When I come out from my workshop we turn to the right, we go to Italy, we turn to the left we go to Germany, we go straight, we go to Austria, we go backwards, we go to France, so except for this paperwork I always enjoyed running the team out of Switzerland.”

“Obviously being based in Switzerland, we are working with Swiss money [but] we are getting paid in European money. In 2011 we had a huge financial crisis with Europe. Our Swiss franc wass miles too strong against the euro. It is still too strong, but in ’11 I had to find solutions with much more work in Switzerland.”

“Obviously being based in Switzerland, we are working with Swiss money [but] we are getting paid in European money. In 2011 we had a huge financial crisis with Europe. Our Swiss franc wass miles too strong against the euro. It is still too strong, but in ’11 I had to find solutions with much more work in Switzerland.”

As the Eurozone debt crisis worsened, investors sought refuge in the most-accessible “hard” currency, the Swiss franc, pushing its value up by 30% against the Euro.

The financial impact was so severe and so sudden that Jenzer came close “at this time, to say I’ve had enough”.

“The Swiss franc in such a short moment got so strong that we were really suffering or having huge problems that the company was able to swim on top of the water and not under the water and this was a time where it was really hard, but we had a huge drive from everybody to push the company through and find solutions.

“We had a very, very tough moment [but] I just worked even double as hard to survive.”

To balance the books, and to ensure an additional and more stable income stream, Jenzer responded by adding “our third business, looking after gentleman drivers, and after gentleman [drivers’] single-seater cars. If you come to our workshop, we have our four F4 cars and three F3 cars but we always have between 25 and 30 single-seater cars in the workshop where we are doing maintenance work, rebuilding work, repairing the cars for track days, and this is the business I had to grow in 2011.”

As for all small businesses, keeping a tight rein on costs is a daily imperative, particularly in the current inflationary environment, requiring the team to be as efficient as possible.

Esther looks after the financial side of the company, and Jenzer admits that “I think she gets a few more grey hairs this year looking at bills coming”. Without external investors, “we are a little bit an old family team, and we have to be able to be competitive with what we have”, he adds.

Photo: Jenzer Motorsport

“We are quite a small operation, with an average of 15 to 25 employees over the last 20 years. With the mechanics and engineers, we are very efficient; quite a few people are doing double things.”

Jenzer has proved itself as a training ground not only for drivers, but also for mechanics and engineers starting their careers in the junior categories. “The list of mechanics and engineers who succeeded with Jenzer Motorsport and made a living out of it is probably as big [as the list of drivers] and that’s another part where we are proud,” comments Jenzer.

He is reluctant to pick any favourites from the “many, many drivers we had in [the team] who brought a lot of enjoyment.

“It’s always a delicate thing to put names because there are many names who made it in different aspects and also many names who probably didn’t make it because of the financial resources.

“Over the 10 years all the success we had with Renault was nice success [but] there is no one particular thing in my memory whether I could say this was really the point,” he says, although he does pick out Nico Muller’s feature race win in GP3 at Silverstone in 2011 as “one of my race wins which I really enjoyed a lot”.

Muller is clearly one of his favourite alumni (“we still have a huge contact”) but adds that “we actually still have a lot of contact with many of our drivers also, there is not many drivers who I could say something negative about”.

“Bruno Spengler was a kind of a character where there was so much enjoyment working with him, and also Neel Jani, who was a completely different character, was an absolute pusher only for results. There are drivers like Fabio Leimer. With the skills he had, with what we were able to achieve with him and what he was able to achieve after, it’s a bit sad to see that he was not able to make it in motorsport.”

Both Siebert and the team’s 2022 FIA F3 driver William Alatalo have continued to work with Jenzer as driver coaches.

Photo: Formula Motorsport Ltd

Alatalo is naturally itching to get back into a competitive seat but says that he has “learned a lot coaching the F4 guys”.

Having experienced life on both sides of the pitwall, he feels at home in the squad. “It’s exactly as a team is supposed to be, everybody is working together just to have everything good for the driver and the team overall.”

Unsurprisingly, motorsport has changed considerably in 30 years. Racing is safer, more popular but also more commercial. The changes, good and bad, permeate all the way down from the top to the bottom of the ladder.

“The last couple of years, I have to say that there are a few sporting things or political-sporting things that make me think a bit too much what I want,” Jenzer says.

In particular, the professionalism in entry-level categories is squeezing out traditional outfits like his own, Jenzer fears.

Too much testing is driving costs up, while the dominance of F1 junior programmes and the concentration of well-funded drivers with one or two teams leaves small points for the rest to fight over.

“I found myself thinking too much about things in the sport what I don’t like or I would like to change. But I always say when you want to enter politics, then you have to do politics, and you have to help yourself to exit or try to change something.

“I’m really a motivation-driven person and a really sports-driven person and not a business-driven person. I don’t like that huge business around the sport.”

Where he still gets a buzz is from working with young drivers and the feeling that “with this driver you can go out there and try to win”.

Jenzer and Spengler

“But today a lot of drivers have to do 10, 15 or 20,000 kilometres before even thinking about getting in a race or winning a race. Raw talent still matters but it doesn’t matter like maybe in the old days.”

“Maybe I am thinking a little bit too much last couple of years. This is a bit a part, especially in the junior categories, when it’s difficult to give an answer. But I am always driven by the sport and I want to go forward.”

After 30 years, Jenzer is not yet ready to hang up his headphones for good but accepts that the time to move on is approaching rapidly, within “the next three to five years”.

“Esther actually has [reached] retirement age. I am only three or four years away from it. There is also a lot of things in the world I want to see. And maybe it’s a bit the moment to have different job objectives.

“Esther and me are the owners of the company. Nobody is paying our salaries, we are earning our salaries. We are doing still all our decisions ourselves.

“We don’t have to come to the circuit [for each event], but we want to come to the circuit. And there is no time where I don’t like to go to the circuit. Because when you are 60 to 65 years old, you can have a much easier life staying at home.

“We are not money-driven. We don’t need to go to the circuit to make money. We don’t need to be here. We are well enough to also have an easier life.

We could “maybe run GT cars where the first session is only at 10am and not like in F4 where the first session is at 8am,” he says.

“In FIA F3 at Silverstone we had to leave the hotel at 5:30am without breakfast. If you do this still at 60 or 65 years old, you must have some sort of a passion,” he laughs.

Photo: Formula Motorsport Ltd

One thing is certain, he says: “We will remain in motorsport. I have fuel in my blood and I will not be able to do something else than motorsport, but I don’t know exactly which direction we’re going to take in the next thing. Maybe we get to build a race track in Switzerland because now it’s allowed to have a race track in Switzerland, I would like to be involved in something like this.”

Jenzer laughs at the suggestion that we might see the development of a circuit named Jenzerring somewhere in his homeland.

“Maybe not a Jenzerring somewhere, but I have to say if our government rule [banning motorsport] would have been ditched 25 years ago, I think people like Peter Sauber, like Emil or Walther Frey, like Fredy Lienhard with Lista, big players in industry, big players in the automobile world would have probably sat at a table and decided let’s build a race track because we had some really, really super passionate people in Switzerland.”

“To survive 30 years in this shark pond is not an easy task. Esther and I are still together. Even if we have hard time sometimes, not in private life but in terms of business.

“My passion is: I really love single-seater racing. And I still love to go to the circuit; not for a money reason [but] to try to teach young kids and to do the best possible job.”

Jenzer is one of the last of a dying breed, the family-owned and managed racing team, competing at the highest level. Its re-emergence as a race-winning outfit is thoroughly deserved, a testament to what can be achieved with talented drivers, even on a budget.