Photo: National Archive of Singapore

Since 2008, the Singapore Grand Prix has become one of the most popular motorsport events on the planet, with its spectacular floodlit scenery and high-commitment circuit layout around the Marina Bay.

The race had a long history before becoming a Formula 1 event, starting back in 1961.

Like many debuting F1 races now, Singapore of the late 1950s was home to a growing economy with an increasingly global appetite. It was benefiting from the rise of commercial jet flight, but the average stay of tourists was just three days.

While tourism really wasn’t near the top of the Malaysian government’s agenda (this being pre-independence Singapore), the potential of the tropical island paradise was obvious – not least for government coffers.

By 1961 the Ministry of Culture had caught on and ran ‘Visit Singapore – The Orient Year’, a sports-focused campaign to bring more people to the nation. Over the weekend of September 16-17, the first ‘Singapore – Orient Year Grand Prix’ was held.

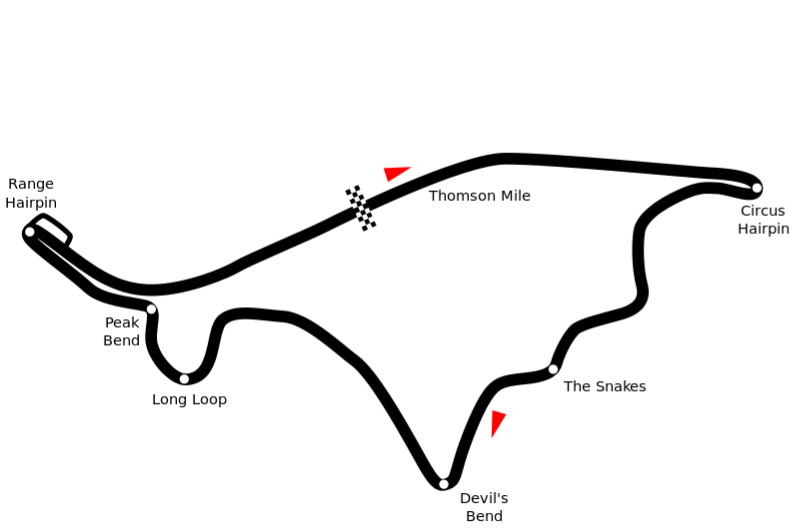

100,000 people were expected to visit the Thomson Road circuit, located 20km north of the current F1 venue. The 4.865km layout was a terrifying mix of high-speed sweeps and tighter turns of varying camber, and the asphalt was of varying quality due to the cost of repairing or repaving anything more than very short stretches of road.

Track design by Readro

Thomson Road was picked with fans in mind, with suitable nearby roads for bus services and elevation to please spectators.

F1’s Malaysian GP was known for its extreme humidity, and Singapore organisers faced the same problem. They ensured all circuit staff had access to free drink, that additional telephone lines were made for ambulances and electricity connections to bypass the problem of burnt out electrics.

The biggest hitch of them all for the 1961 race was that its first scheduled date was during a public holiday, which complicated not only how many people would be available and willing to work that weekend, but if several government ministries and labour unions would allow it, especially when it came to the requirement of a police presence.

A different date was picked, the weekend of racing went ahead without too much issue and proved popular enough to earn the Malaysian GP moniker until Singapore declared independence.

It was at this point, in 1966, that the grand prix focused on being the fastest junior single-seater race in the Far East. The event got bigger, the prizes got larger, and subjectively the drivers got better as entry opened up internationally to drivers outside of the Singapore Motor Club membership.

Singaporean Lee Han Seng won this ‘first edition’ of the race, sponsored by big international brands, but local knowledge only lasted one more year before international stars started winning.

Kiwi talent Graeme Lawrence triumphed three times in a row between 1969 to ’71, and won eight other junior single-seater races with grand prix titles in Asia during his career.

Max Stewart won the 1972 race, with fellow Australian Vern Schuppan winning the final fateful edition of the race a year later – the last Singapore Grand Prix before 2008.

Schuppan’s career started in Formula Ford 1600 in Britain, but after one full season jumped to racing Formula B/Atlantic – a Formula 2 level category with Formula 3 level running costs – and won the 1971 British title. Using the same cars in the junior single-seaters grands prix of Asia (including Selangor and Macau), he quickly launched himself into F1, IndyCar and then the Le Mans 24 Hours with success.

“Bearing in mind I’d never raced in Australia, I hadn’t raced when I moved to England in 1969. So the first time I’d come up against [fellow] Australian drivers was in Singapore,” Schuppan tells Formula Scout.

“It was exciting for me, the drivers who came up [to race in Singapore] were guys that were generally older than myself. Guys I’d followed while I lived in Australia. They were fairly famous names, [like] Kevin Bartlett. There was a bunch of well-known drivers, some that are still around.

“Also Jack Brabham was out there, so considering I’d only been racing less than a couple of years at that stage, it was quite an exciting time to meet those guys and race against them.

“I guess Thomson Road was dangerous [by the standards of the time], with very large drainage areas either side of the track. The car would go in there and disappear sort of thing, if you happened to go off the road. Plus being fairly hilly, there are a lot of drop offs from the road.

Vern Schuppan during his time in IndyCar

“In fact, I crashed there. I took my virtually new March out there and had a rear suspension break during the first practice or qualifying, and I was lucky not to have a much more serious accident than I did. We managed to repair the car and I finished up racing it. Starting from the back because of not qualifying properly, I finished second in that 1972 race.”

The track rewarded bravery and was a driver favourite, but with powerful FB cars charging around it by the early 1970s and little in safety improvements, it was without exaggeration a death trap.

Although the FB cars were laden with downforce thanks to sticky tyres and large aerodynamic appendages, drivers still had to lift to avoid take off on ‘The Hump’, a right handed kink that acted as the first corner and the highest point on the track.

Cars were often modified too to enhance performance. With so much of the track at full throttle, they were filled heavy with fuel, so holes were deliberately put in the bodywork in the pursuit of weight loss. This of course made the internals, and driver, more susceptible to roadside debris.

Effective brakes were hugely important (but not common beyond the FB cars), with three major hairpins, two of which came at the end of high-speed sections. One difficulty was that the Circus Hairpin also came after a lengthy descent, meaning gravity often took control. VIPs, predominantly government officials, had their stand positioned here.

The tropical climate and unforgiving track made it mechanically gruelling, primarily due to the rocks that littered the track.

As the race was run to a ‘Formula Libre’ format, there was also F3 and FF1600 cars to contend with. Down the Thomson Mile, the straight split by The Hump, lapping slower cars was still difficult and the number of incidents that occurred there meant the stretch was colloquially known as ‘Murder Mile’.

In 1972, Singaporean Lionel Chan rolled into a marshal’s car and died, although there are conflicting reports on the exact circumstances of his death, while two-time Macau GP winner Jan Bussell escaped a crash where fuel set one of his rear tyres and then his entire car in fire.

Through The Snakes that followed, a tree and ravine-lined equivalent to Suzuka’s ‘S’ Curves, attempting overtakes was a near death wish. It was the hairpin immediately after, Devil’s Bend, that cast the largest shadow though.

While the grand prix proved as popular to drivers and fans in East Asia, the circuit was too dangerous to host the organisers’ growing ambitions, but a permanent circuit to replace it never got further than the planning stage.

Institution support evaporated after 1973, when Joe Huber died in a supporting touring car race – avoiding a fruit plantation but hitting a pole instead. The fatality count, an increasing amount of road traffic accidents occurring in the country, and a host of other socioeconomic factors meant the presence of the race could be justified no more.

It wasn’t just the race that was stopped after 1973, but motorsport itself. But this didn’t stop various parties trying to revive it.

Australia, New Zealand and Macau were some of the other Pacific nations running international grand prix events for junior single-seaters, and in 1985 the Australian race was granted F1 world championship status on a new street circuit in Adelaide.

The men behind Adelaide wanted to bring motorsport back to Singapore and Thomson Road, and aimed for a spot on the 1990 F1 calendar. That date was pushed back by a year by the time the Singapore government had approved plans for a grand prix return, and at a new location 15km east of the current Marina Bay track.

At a conservative cost of $30 million, the expo-style venue was supposed to include ‘space for exhibitions and a leisure complex’ in addition to the grand prix circuit. With more emphasis on private sector involvement, the plan failed and the land is now home to a lagoon-filled golf course and the promised expo centre.

In May 2007, Bernie Ecclestone signed a deal that brought Singapore onto the F1 calendar as the first ever night-time grand prix. On the support package was Formula BMW Pacific, in which Romanian Doru Sechelariu took a double win. Felipe Nasr did the same a year later, and in 2010 the wins were split between Singapore-licensed Brit Richard Bradley and Oscar Tunjo.

For 2012 and ’13, the cramped support paddock was occupied by GP2, and junior single-seaters have not been seen there since. Formula 4 South East Asia planned to visit in 2017 but never did, and with the growth of Asian F3 surely it’s only a matter of time until young drivers are making their names on Pulau Ujong once again.