Photo: Formula Motorsport Ltd

Some champions win lots of races, others consistently finish in lower positions and that is what enables them to outscore rivals over the length of a campaign. Are there impressive examples of the latter?

Many think this year’s Formula 2 champion Theo Pourchaire deserves a place on the 2024 Formula 1 grid, while others believe the way in which he won the title in his third season means he didn’t show enough to merit a step up.

In the end, Pourchaire has earned his place at the top level of single-seaters, in Super Formula with Team Impul, but the fact that he became F2 champion after winning just one race in 2023 cannot be ignored.

Winning a title in open-wheel racing’s second tier, which currently consists of F2 and Indy Nxt, is historically the most effective way to earn a seat in the top tier. A scholarship system for Indy Nxt’s champions has ensured most have been in IndyCar the year after, while the F2 title contenders tend to be F1 juniors so their readiness for a seat is already known by the team that supports them. Therefore if they get overlooked, like in Pourchaire’s case with Sauber, it can make others in the paddock think they’re not ready for F1 either.

Alpine even overlooked its junior Oscar Piastri after he won six races and the title as an F2 rookie in 2021, but McLaren poached him to prove Alpine wrong. Piastri couldn’t have done much more in F2 to show he was F1-ready, whereas it could be argued that had Pourchaire won more races he would have not only been champion by some margin but also be F1-bound.

In fact, Pourchaire had the second lowest winning rate for a champion in the entire history of second-tier single-seaters.

Formula Scout has omitted the Soviet F2 series of the 1970s and Formula Libre-spec championships (such as fellow Eastern Bloc competition Formula Easter), and Australian F2 was sometimes comparable to its European counterpart but ran for many years using the category name even when its cars were more comparable to ones from single-seaters’ third tier.

A FEaster car being driven at Goodwood

It did have multiple champions though who only won one race, primarily because of short seasons. Richard Davison turned up halfway through the four-round 1980 season, won at Calder Park, finished second at Sandown Park and that was enough to win the title. Graeme Crawford was also the champion of a four-race campaign, and contested all four rounds, in 1976.

A much more recent example of a second-tier series only featuring four races is GP2 Asia in 2011, which marked the debut of the Dallara GP2/11 car. There was supposed to be three rounds of two races each, but two of them in Bahrain got cancelled due to anti-government protests and there was only time for one replacement event: at Imola in Italy.

Romain Grosjean took pole and finished second in the feature race of round one at Yas Marina Circuit, then won from pole in the Imola feature race. He failed to score in the other two races but was still champion by five points. He went on to win the main GP2 series that year too in far more dominant fashion with five race victories, earning himself a Lotus F1 seat.

A series that has stuck to using second-tier single-seaters through its 50-year history, but doesn’t attract rising stars anymore, is Atlantics. Drivers used to choose between competing in that or Indy Nxt as their final step before IndyCar (or Champ Car prior to the two merging in 2008), and Bill Brack won the first two seasons in 1974 and ’75. He claimed his second title by winning just one of the six races, while entry lists had depleted so much by last year that Keith Grant became champion by contesting six of the season’s 10 races and winning one. No Formula Atlantic cars even entered the final round.

In 1982 there were eight different winners in the first eight races, and most of them went into the ninth and final race at Mosport in title contention. Whitney Ganz claimed his second win of the season there, but the 38-year-old Dave McMillan – who had mised a race – was crowned champion.

Although SF is now a top-tier series, before 1996 the pinnacle of Japan’s single-seater scene was for second-tier machinery. From 1978 to 1986 it ran for F2 cars, then switched to Formula 3000 for the next nine seasons.

Ogawa during his title defence

Satoru Nakajima won five Japanese F2 titles before finally getting the chance to race in F1 in 1987, and his final domestic crown in ’86 was actually his least convincing. He claimed pole for five of the eight races, but only converted one into victory. Similarly, Hitoshi Ogawa took pole for the last three races of the 1989 Japanese F3000 season, had a bad conversion rate with only one win but still claimed the championship crown.

Those are the many honourable mentions, and here are the 10 champions in second-tier single-seater racing with the worst winning rate (based on only winning one race) in their title-winning seasons:

10. Tom Gloy 1979 Atlantics 1 win out of 10 (10%)

This campaign was impressive enough for Gloy to be signed by Team Penske for his rookie CART season in 1980, even though it featured only one win.

Having a brand new Ralt RT1 chassis helped, while some rivals had the same model but their chassis had already been raced for a year or more, and that helped make the difference when reliability came into play.

Two of his rivals – Kevin Cogan and Howdy Holmes – managed to win three races each yet they ended up trailing Gloy in the standings by 45 and 72 points respectively. It was a big margin given Gloy scored 208 points, but the campaign’s five race-winners were the only drivers to score more than 60.

The season began with a Long Beach Grand Prix support race, and Gloy was 0.94 seconds off poleman Cogan’s qualifying pace. But he overcame him in the 51-lap race to win by five seconds. That would be the high point of Gloy’s year in results.

Thereon he relied on consistency to maintain a points lead, finishing second, third and second in the next three races (only missing out on victory by 0.26s in Quebec City) then following it up with his only finish outside of the top four: a seventh place.

At Road America he finally got close to taking a pole and was second in the 25-lap race, albeit 17s behind the winner, then he finished fourth from 15th on the grid at Mosport and was second, second and fourth in the remaining races.

9. Mauro Martini 1992 Japanese F3000 1 win out of 11 (9.09%)

Photo: Martini [9] chasing Irvine and Apicella

So many attempted overtakes that season ended in offs or collisions, and some drivers clocked up as many retirements as they did finishes. That helped Martini take the title, and it’s rather telling that his closest rival was a driver who had four retirements and one points-free finish from the first five races then took two wins and two second places in the next six.

Martini took until round seven of 11 at Fuji Speedway to qualify on the front row, having failed to even start the previous race, and he maximised his position at the front to win while poleman Ross Cheever finished 17th.

A few weeks later Martini could only qualify ninth and finish 10th at the same track, but two podiums in the next two rounds gave him a four-point championship lead with one race to go. He retired from the finale, but only one driver who heading into the race was in the top seven in the standings scored, which sums up the season perfectly.

=7. Simon Pagenaud 2006 Atlantics 1 win out of 12 (8.33%)

Photo: Team Australia

Pagenaud reached single-seaters’ second tier in 2005, coming 16th in Formula Renault 3.5 and failing to make the podium. That meant expectations were not high when the 2004 FR2.0 Eurocup champion moved his career across to the USA for 2006 and joined Team Australia in Atlantics.

Fourth place on his debut suggested he had made the right move, and he finished second in the next two races. At Portland he was already a lap down by lap two and retired from 23rd place a few laps from the end, but he bounced back at the Cleveland double-header with another second place and then his first pole position.

Two weeks later he finished fourth on the streets of Toronto, but with his two title rivals retiring he moved into the points lead. He stayed at the top of the standings for the rest of the campaign, and immediately extended his lead after Toronto in the second Canadian round in Edmonton as he qualified second – 0.013s off pole – and then claimed his first and only win.

In San Jose he finished ninth after getting a one-place penalty for blocking yet extended his points lead, and although he finished third and second in the next two races his main title rival Graham Rahal won both and cut the gap to 12 points.

The season finale took place at Road America, and was a disaster for both title contenders. Rahal was out after five laps, and Pagenaud retired a lap later after contact. It was that moment he was crowned champion, and earned a $2 million scholarship to spend on stepping up to Champ Car. His career in American single-seater racing looks like it has now come to an end.

=7. Robbie Buhl 1992 Indy Nxt 1 win out of 12 (8.33%)

Photo: Richard Spiegelman

The really interesting thing about Buhl’s season was not his low winning rate, but the sports science investigation he and his Leading Edge Motorsport team was part of that tracked how his body reacted to the highs and lows of the title fight.

There wasn’t really any lows though, because Buhl was insanely consistent. He was on the podium in every race until the season finale, taking four second places and six second places to accompany his only win at Nazareth Speedway.

It was Buhl’s third season in Indy Nxt, all with the same team, and he finished second five times in his rookie campaign then claimed one win and three other podiums as a series sophomore but dropped from fourth to sixth in the standings. Only two of the drivers ahead of him in the 1991 season remained in Indy Nxt for 1992 though, so he became one to watch.

He first topped the points after round four, having finished third twice then second twice, and returned to the top in Toronto (round seven) with his next second place finish. With two rounds to go, and before he had won a race, he already had a points lead big enough to be able to skip a race and still be ahead. Therefore, his victory in the penultimate round at Nazareth also delivered him the title.

Had there still been something to fight for at the Laguna Seca finale, he probably would have qualified higher than seventh and finished higher than fourth.

Buhl was not quite as consistent in qualifying as he was in races, and in a field that varied in size from 11 to 20 cars he never qualified lower than seventh and had an average starting position of 3.25 thanks to three poles.

=5. Kevin Ceccon 2011 Auto GP 1 win out of 14 (7.14%)

Photo: Auto GP

A teenaged Ceccon burst onto the scene by winning the Auto GP title by three points as a rookie, a success which led directly to GP2 appearances and an F1 test call-up with Toro Rosso in the same year.

But he lacked the budget to build momentum, instead stepping down to GP3 for 2012. He returned to GP2 in 2013 for six rounds, then was back in GP3 for two more years. After trying out sportscars, he found a home in touring car racing in 2018.

Anyway, back to Auto GP. It began in 1999 as Italian F3000, became a European contest in 2001, returned to being Italian F3000 in 2005, then was Euroseries F3000 again before adopting the Auto GP name and old A1GP cars in 2010. A few tweaks to the chassis, while maintaining the huge 550bhp engines, turned them into junior single-seater cars.

Ceccon had spent his first two years in cars racing in Euroformula (then known as European F3 Open), winning one race and coming fourth in the 2010 standings. When he stepped up to Auto GP his opposition included established GP2 stars.

It’s no surprise that the young and skinny Italian didn’t set the pace against experienced and older opposition, but he displayed great maturity and consistency and the series-organising Coloni family handed him several outings with their GP2 team. He became Auto GP champion thanks to 100% attendance, as his four closest title rivals missed races before the eight-way title showdown at Mugello. It was still a four-driver fight in the final race, but none of them made the podium and Ceccon became champion in seventh.

He took five podiums, with his sole win coming in his third start at the Hungaroring, and made the front row once with an average qualifying position of 4.14 and average deficit to pole of 0.425s.

=5. Wade Cunningham 2005 Indy Nxt 1 win out of 14 (7.14%)

Photo: IndyCar

Cunningham did make it to single-seaters’ top level, but over five-and-a-half years after winning the 2005 Indy Nxt title.

He got the job done as a rookie, but contested the next five seasons since the rules at the time did not forbid champions from remaining in the series.

The New Zealander was another example of consistency rules, since he only once finished outside of the top five in his title-winning campaign. Winning the season-ending California 100 oval race was what clinched him the title, and before that he had already come home second seven times – including a run of four runner-up results in a row – and picked up two third places.

He set the fastest lap on his race debut, and the fact his maiden pole (and front-row start) didn’t come until the penultimate round showed that his strength lied in the races. Cunningham qualified seventh and ninth for his first two races, but converted that into fourth and third places, From an average starting position of 4.64 he had an average race position of 3.14.

In his title defence he improved to three wins and four poles, but missing the St. Petersburg races due to having his appendix removed at the start of the race weekend left him 11 points off being a double champion. There was one win and two poles as he came third in the standings again in 2007, in 2009 he became the only multiple-time winner of the Indianapolis 500-supporting Freedom 100 and then he won it again in 2010. He made five IndyCar starts in 2011 and ’12.

=3. David Empringham 1993 Atlantics 1 win out of 15 (6.67%)

Photo: Marshall Pruett

This was an all-out battle of the Canadians. In one corner was Canaska Racing’s Empringham, and in the other was Forsythe-Green Racing duo Claude Bourbonnais and Jacques Villeneuve.

All three had series experience. Empringham had picked up two wins and three second places from a part-time campaign in 1992, Bourbonnais had a best finish of fourth and a pole from six races, and Villeneuve had made the podium in a cameo.

The trio were overshadowed in round one, but then became the drivers to beat through the rest of 1993. Villeneuve took pole but Bourbounnais won in Long Beach, then converted first on the grid into first at the finish at Road America. Bourbounnais won again at the Milwaukee Mile, then Villeneuve won in Montreal before Bourbounnais struck back at Mosport.

All the while Empringham was racking up podiums, with one second place accompanied by four thirds and the points lead. He also got pole in Halifax, but Trevor Seibert beat him to being the third Canadian of 1993 to win as Bourbounnais non-started.

Bourbounnais won the next two, taking the points lead at New Hampshire Motor Speedway where Empringham didn’t start. He won Grand Prix de Trois-Rivieres (which he did again in 1994 and ’95) to move back ahead, but his form then dipped with two podiums in the last five races. Bourbounnais led again with two races to go, but lost the title when his engine failed 13 laps into the season finale. Empringham finished fourth to take the crown by four points, with Villeneuve a further six behind.

=3. Nicolas Prost 2008 Euroseries 30000 1 win out of 15 (6.67%)

Photo: Euroseries 3000

Prost had to wait almost six years between winning the Auto GP title and debuting in single-seaters’ top tier, and what an impact he made in the inaugural Formula E event as he claimed pole and infamously lost the win at the very last corner.

He started his car racing career with a year in FR2.0, then two in Spanish F3 where he came third in 2007 with two wins. Euroseries 3000 beckoned after that for the son of four-time F1 world champion Alain, and he only had three full-time rivals to contend with. None of whom were expected to set the grid alight with their talents.

Yet Prost only won the title by two points, and five drivers had more race victories than him. He wasn’t even a model of consistency, with his haul of six podiums being matched by his two closest title rivals – one of whom missed two rounds. The season finale at Umbria had four title contenders, and points leader Prost qualified fourth, retired on the opening lap of race one then finished a points-free seventh – 45s behind the winner – in race two to make himself champion.

Prost did the start the season with pole, by just 0.014s, and turned that into a third place finish in his debut. It was a result he would not beat until his maiden win in round six at Jerez – where he also took pole – and catapulted him into a 10-point championship lead. In the remaining five races, which eight drivers saw out, he was outscored by five drivers and one scored almost three times as many points as him in that time despite a second-place finish at Barcelona.

2. Theo Pourchaire 2023 F2 1 win out of 26 (3.85%)

Photo: Sauber Group

The modern trend of expanded calendars in F1 and F2 is why Pourchaire’s title success looks so underwhelming. He had 26 chances to win, and only converted once. His main title rival Frederik Vesti won six times, and rookie Ollie Bearman four times.

Pourchaire got his victory out of the way early, winning the first feature race of the season at Bahrain from pole, then had three points-free races before finishing second in the Melbourne feature race. He followed that up with another non-score, dropping one place to third in the standings, but third in the next race put him back in the points lead.

The championship lead was lost in Monaco despite claiming a fourth feature race podium out of five, and he didn’t top the table again until 20 races into the campaign. Two weekends in which he made the podium in both races led up to that point.

After the summer break, there were three more rounds and a lead of 12 points to protect. The Zandvoort sprint race was so short it didn’t award points, then none of the top four in the standings scored in the feature race – three of them retired early on.

Pourchaire grew his gap with a fourth and a third at Monza, and pole position showed his title-winning pace. At Yas Marina Circuit he put tiredness and a water leak down to his worst qualifying result of the year – 14th place – but rising to seventh and fifth in the two races was enough to be crowned and become the 23rd driver in GP2/F2 history to score 200 points in a season but the first in the 57-year history of F1’s primary feeder series to become champion with just one race win.

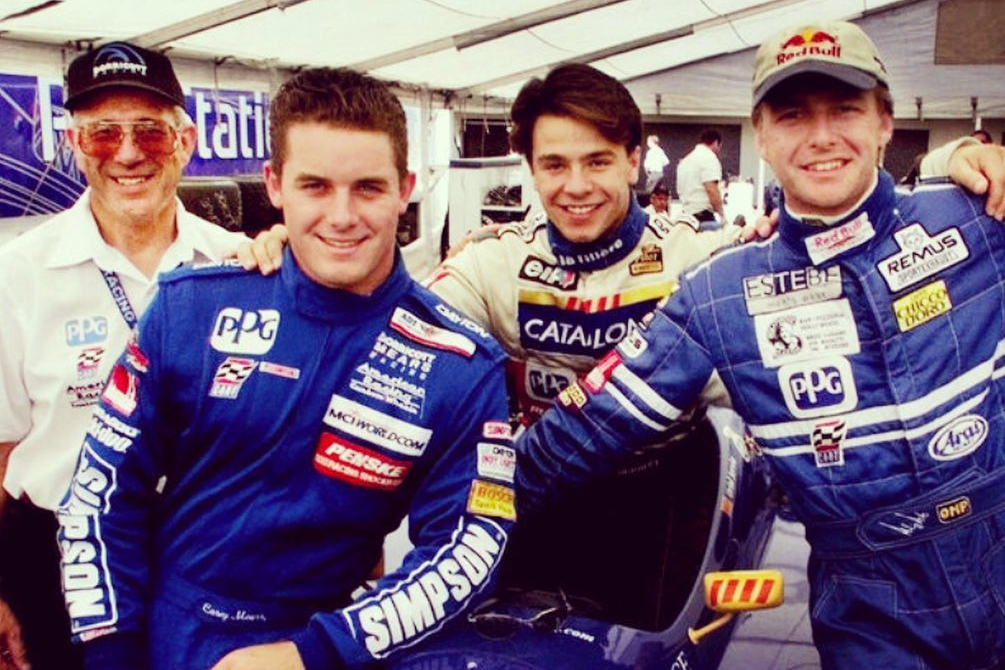

1. Oriol Servia 1999 Indy Nxt 0 wins out of 12 (0.00%)

Photo: Oriol Servia

It was crazy enough that Servia won the 1999 Indy Nxt title without ever standing on the top step of the podium, but the fact his title rival and Dorricott Racing team-mate Casey Mears didn’t either makes this a huge statistical anomaly.

There were two drivers who took two wins each, but ended up third and seventh in the standings, while Servia’s title charge was built on five second places and Mears split his four podium results into two seconds and two thirds. Two drivers outside of the top 10 in the standings won races, and for both their victory contributed to around a third of their total points.

Servia came seventh in the 1998 season as a rookie, getting two podiums, and of the drivers ahead of him in the standings all but the champion returned for 1999. Mears meanwhile had two seasons of experience and in ’98 was 17th in the points.

The year began with Mario Dominguez laying down his title credentials with victory at Homestead-Miami, with Mears and Servia a very distant fifth and sixth. Domingues came nowhere near close to replicating that result thereon, but still led the points after round two in Long Beach which Philipp Peter won. The Dorricott drivers finally looked competitive at Nazareth, with Servia taking pole and finishing second, just ahead of Mears. But an 18-year-old Scott Dixon now led the points.

Mears made the podium at Milwaukee to move to the head of the championship, then Servia went on a run of second places at Portland, Cleveland and Toronto to build a big points lead over his team-mate. Servia’s next second place in Detroit put him 20 points clear (equivalent to a win) of Mears and Peter, while 1998 title runner-up Didier Andre was 12th in the standings.

Servia finished fourth, seventh and 14th in the last three races, with Mears doing slightly better with a third, a fifth and a 13th, and that comfortably secured them the top two places in the championship. Peter petered out after his third win, while Jonny Kane, Dixon and Andre suddenly became the form drivers. Kane won the finale (by just 0.049s over the Stig) from pole and rose from ninth to fourth in the standings, Dixon took a win and a second to climb from eighth to fifth, and Andre almost doubled his points tally with first and third in the final two races to lift himself from 12th to eighth in the points table.