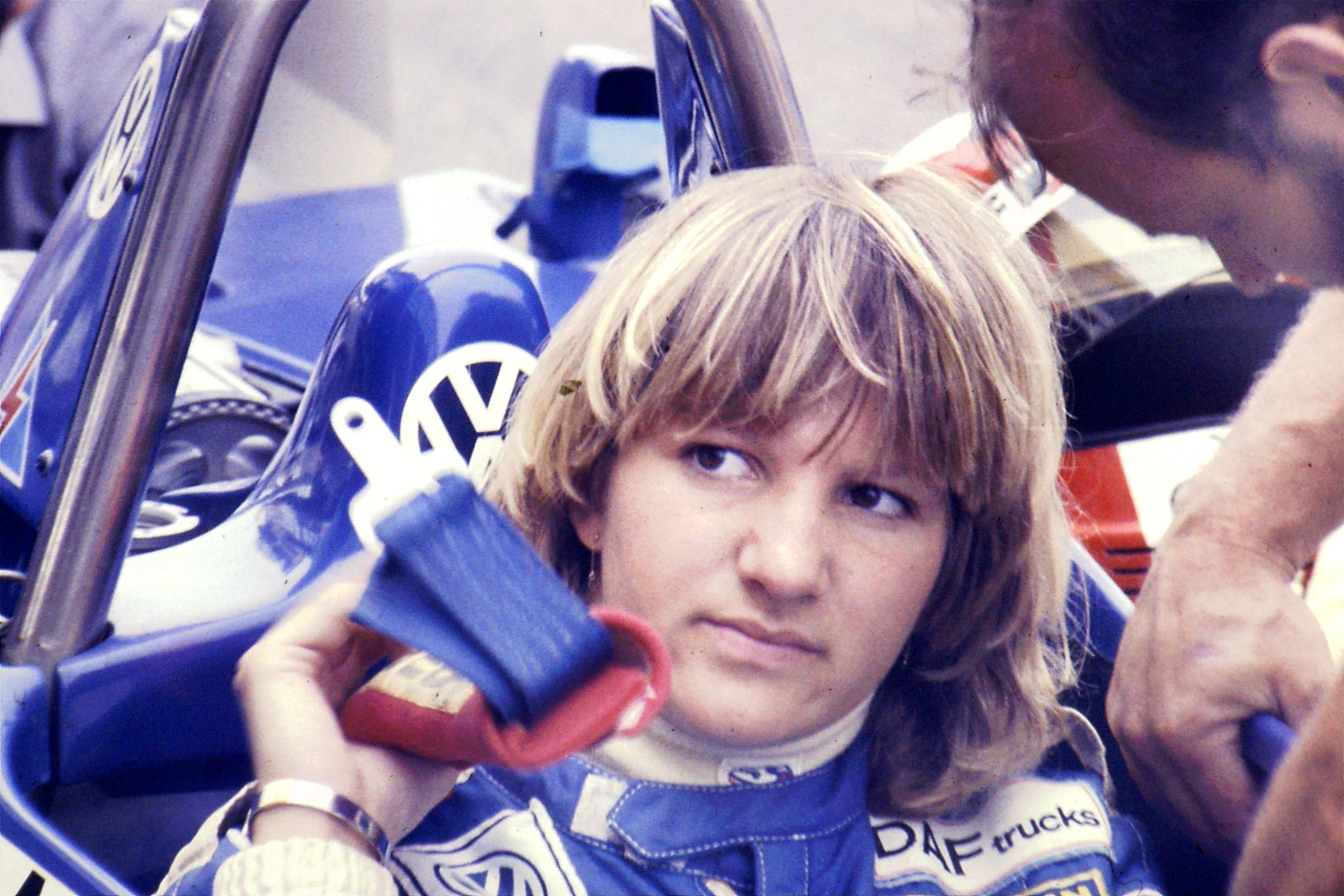

Photo: Gerard Kraaijenoord

To mark the 40th anniversary of her landmark French F3 win at Albi, Cathy Muller joined the Formula Scout Podcast to discuss her varied career, her racing family and women in motorsport

Cathy Muller is unique within motorsport: a European karting champion, a Formula 3 star in the 1980s, the sister and mother of touring car world champions Yvan Muller and Yann Ehrlacher respectively, a racer in touring cars, sportscars and even ice racing, a team manager, active within the FIA and now supporting the Iron Dames project.

Yet despite these remarkable achievements, her name will mean little to most racing fans today. Memories are short. When Sophia Floersch finished seventh in a FIA F3 Championship race at Spa-Francorchamps in 2023, her result was hailed as the first ever F3 points finish by a woman. She had scored in FIA European F3 in 2018, and others in the category had before that.

Muller and Ellen Lohr, as well as others such as Claudia Huertgen, had been regular F3 points-scorers in the 1980s and ’90s. Across her five seasons in F3, Muller racked up 46 top-10 finishes. She joined the Formula Scout Podcast [listen via the link at bottom] to recall that period of her career and much more.

Muller came from a racing family. “My father was racing in hillclimbs in 1974. My parents bought me the first kart and after my father stopped racing, we went on the race track and we started like that. I was 12 years old,” she remembers.

But karting was more than a hobby. After winning the French junior title, the then 17-year-old became the first female European karting champion, taking the 1979 100cc title at the Biesheim circuit, close to the family home in Alsace. “There were only men [racing], I was the only girl,” Muller recalls with a smile.

She would go on to take a world championship, “but it was a women’s championship, so it was not that important,” she adds slightly dismissively.

There was also fifth place in the prestigious Race of Champions (Coppa dei Campioni) held at Jesolo in Italy. “At that time it was a very big race. It was like a world championship so everybody was there like [Ayrton] Senna, Mike Wilson, [Terry] Fullerton, all these top drivers.”

Amusingly, her fellow competitors couldn’t believe that a woman had beaten them. “Nobody really knew that there was a girl. It was not like today [when] everybody knows everything. When I went to take my trophy at the prize giving on the Sunday evening, they were surprised that there was a woman, or a girl, I was very young, and they thought the driver had sent his daughter. But then they found out that it was a girl!”

Muller herself was unfazed. “I didn’t really care. I was there like a driver. It was funny to find out that many people were surprised that there was a girl, but that’s it.”

For 1981 she moved up to cars, initially in the Renault 5 Turbo European Cup but her big break came later in the year after she enrolled in the Elf Winfield school at Magny-Cours. With the backing of Elf, the French state-owned oil company, French motorsport was booming, with a host of future Formula 1 drivers passing through the Winfield school.

Under the watching gaze of Alain Prost, Didier Pironi, Jacques Laffite and other racing luminaries, Muller shocked onlookers by winning the final.

“It was not easy to win, because first we went out and from 300 drivers there was only 10 left.” The field was reduced to five drivers for a five-lap shootout in the grand final. After leader Gilles Lempereur spun, it was Muller who came home first.

However, so great was the disbelief of the jury that they ordered a re-run of the final. Muller won again.

“[Some watching F1 drivers said] ‘ah, that’s great, it’s a girl’, some of them said ‘no, it’s not possible that a girl wins this school’ because it’s only men who [previously] won this school, and men who were now in F1, and were part of the jury. So they said ‘okay, you drive again another heat, with the other ones’ [competing to win]. It was the first time it happened like that.

“We even had to change cars and then we drove the heat again. And every time I went on the track I was faster and faster and faster. And that’s it. I won Winfield Elf school. It was something really very, very nice [and] gave me the chance to have a budget for the year after to do Formula Renault.”

There is a great photo [above] with Muller holding the trophy inside the car, as a who’s who of French motor racing of the time looks on.

“I did the whole year in FRenault [France]. I progressed very well and I won the last race, the final [at Paul Ricard], which was very helpful because then I moved into F3, the European championship.”

She led home Lempereur again in that FRenault race, putting her fifth in the standings while he won the title.

With continued backing from Elf, Muller joined Dave Price Racing for 1983. There was Senna, [Gerhard] Berger, [Emanuele] Pirro and so on, so it was very nice. It was a very good learning year.”

Muller switched to MC Motorsport for 1984 and came 11th in the standings with a best result of fourth at Knutstorp. She finished in the top seven in nine of the 12 races she contested. She also did the 1983 Macau Grand Prix, the first time the race ran for F3 cars, although remembers very little: “I have some flash like that, but I remember only that it was incredible. A good experience. I was quite good on [street] circuits.”

However, the highlight of Muller’s single-seater career and “one of my best memories” came in September 1984 when she took part in a round of the French F3 championship on the Albi airfield circuit.

“At that time my team, the French press and the French drivers said: ‘The European championship is not at a good level. It’s not worth it. The French championship is much better etc.’. The boss of my team had heard enough so he said ‘okay, we’re going to do a race there’. I said ‘Are you sure? Okay, let’s go there.’

“We went there to Albi and I remember there were three corners just after the straight and I was the only one to take these corners flat. I won the race and it was incredible. My mechanics had written on the pit board ‘thank you’, so I think it’s one of my best memories because what is important in racing for every driver is to be very, very close to the team, it’s a team win.”

She tells another humorous story from after that race. “That’s where Jean Alesi said that he saw me making ‘pee pee’ against a tree. It mean that I was not a woman, I was a boy. They tried to find an excuse [for] how they could be beaten by a woman.”

As with her Elf Winfield victory, there was shock. How could a woman win? “They took my car apart after the win, they looked if the tyres were correct, because they said there is something wrong, because it’s not possible she wins.”

Naturally, all was above board. “But that’s how it was at that time. I’m not complaining, at that time if a woman was racing on a circuit, and if you take a boy on the braking, the boy doesn’t like it. So, he prefers to crash than a girl overtakes [him]. I didn’t care. It was their problem.”

Since Muller’s win, there have not been many comparable results by women in contemporary junior single-seater series at the third tier. Rahel Frey won from pole in a German F3 race at the Nurburgring in 2009, and Juju Noda was victorious at Paul Ricard in Euroformula last year but was racing with an officially-sanctioned weight advantage.

Muller gained something of a reputation for her feistiness on track. She agrees but points out that as a woman she had to give as good as she got.

“Of course, you have to be aggressive, even doubly aggressive. The problem was more at that time, but it’s still a little like that now, when there is a woman faster than a boy, you are not sympathique [likeable], you are perhaps not a woman, you are not nice. Do I care? No, it’s their problem.

“The only year where I didn’t have any problem, was the year where Yvan and myself have been driving in the same team. We had the same colour of the car and we had the same helmet.

“There was no radio like today. I never had any problem because they never knew [whether] it was Yvan or me. Much easier, much better and overtaking was normal. That’s how it was. At least it gave me more power and made me stronger. I never give up.”

Talking to her leaves you in no doubt that she was prepared to fight her corner against the men.

Photo: Gerard Kraaijenoord

With the demise of European F3 at the end of 1984, Muller made the move to British F3, then considered the category’s strongest series in. She continued to have Elf’s backing and was back with DPR, who had run the previous year’s champion.

At the time, her arrival was nothing short of sensational. Partly because relatively few Europeans were in British F3, but mainly due to Muller being a 22-year-old woman.

Illustrating the progress in social attitudes in the intervening 40 years, references were as much about her looks as her performances on track. The programme notes for the opening round at Silverstone described her as “the attractive French lady [whose] hard driving, late braking style… could raise more than a few eyebrows”.

Later in the season, she was described as “adding a little glamour to proceedings”. while aiming to “turn a few heads, on the track, as well as off it, this afternoon”.

It turned into a tough year; Muller taking two fourth places and frequently running in the points but never quite getting the breakthrough to make podiums possible.

And she was dreadfully homesick. “For sure it was a mistake for me. I was in one of the best teams but I need to have the family [around me]. We are always all together and I think I was not ready to go away from the family. We live in a part of France where the people are very much more hospitable. When a stranger comes, we look after him.

“In England, after the race I didn’t even have time to [get] changed. I had to go home with the overalls because the team went and that’s it. I was just not ready to go there. I needed more family ambience, so all the racing was not that interesting.”

In 1986 Muller was able to move up to International Formula 3000, one step away from F1, but was handicapped “because we didn’t have the budget”.

“My first race in F3000 was in Pau. No testing, nothing before, so it was quite hard, but it was incredible. Now you go to the simulator or you go to do some test. I was just doing my seat [fitting] in Pau and then straight away in the testing with the F3000. We just had enough finance to do that, but we didn’t have the finance to do the whole season and to do the preparation.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, she failed to qualify there, and switched teams twice before the end of a difficult season.

She made a return to F3 for 1987 [pictured above], and teamed up with brother Yvan under the Ecurie Elf banner for 1989. “We did the team together because it was easier and the cost was much less. We did everything ourselves. I was doing all the organisation, all the logistics. It’s not the best way to do it. It’s better always to be with a constructor.”

And Muller was already thinking more of her younger brother’s wellbeing than her own racing. “I was more worried about what Yvan was doing, because usually he was in front of me,” she explains.

At the end of the season, she got an opportunity in single-seaters’ second tier again, this time in Indy car racing’s primary feeder series Indy Nxt. Here, unlike the cold English, she encountered a much more welcoming environment.

“America was really incredible. The people were very warm, and everything was new,” she says.

“I [was] invited to do a race in Laguna Seca. Then the year after they said ‘okay, come over if you want to race because we have a budget, etc.’.”

After beginning 1990 on the Phoenix oval, she headed to the streets of Long Beach for the second race. “I was in the same hotel as the Indy [car] drivers [including] Mario Andretti. I went into the elevator and there were two or three drivers, and they said ‘hello, how are you?’. I looked behind me to see who they were speaking to because I never thought they were speaking to me

“Then they said ‘if you need anything or you need some tips, don’t hesitate to come’. That was really a nice welcome.”

Round three was back on an oval at the Milwaukee Mile. Muller was going well until an error cost her dearly.

“I had the best time. I was on pole position. They told me to come in to change the tyres. The pit was very bumpy and at the time, you had no [speed] limit in the pits. I [hit] this big hole [and] went into the pit barrier. ‘Oh my god,’ I said. ‘No, it’s not possible I did that’. So I passed from pole position to dead last, and after it the rain came. They repaired the car very fast, and I went out again and I was top five again. It’s not easy when you don’t know the ovals but it was interesting.”

The team was very apologetic for not warning her. “But I should have been more careful. I didn’t want to get out of the car. You know, I was in the car, and I said ‘oh my god, I’m not going to take my helmet off’.”

Ultimately, just as she was getting to grips with the US scene, having taken consecutive fifth places at Meadowlands and in Toronto, her season was over. “My big sponsor had to stop because of the Gulf War. So I came back to France.”

Despite the welcome from competitors and fans in the USA, she still missed home. “I’m not sure I was ready to leave my home and my family to go over there. I was probably a bit too young, but for sure it would have been really great to continue over there. Regrets? No, I don’t have really regrets. I did other things after which were very nice.”

And she still had the feeling of competing in a man’s world. “At that time, it was not very popular to be a woman racing because [there was a] feeling that if I was in front then the level of the series was bad.”

Having already had a couple of outings in the World Sportscar Championship, she got a last minute call to drive a Spice prototype at the 1991 Le Mans 24 Hours for the Japanese AO Racing team.

“The Japanese girl [Tomiko Yoshikawa] didn’t get the superlicense [so] they called me the Monday before Le Mans to say ‘come over, come to Le Mans, you are going to do the race’.”

Photo: Roger Gascoigne

So, with no testing, she joined an all-female crew with Desire Wilson and Lyn St James, the crew being dubbed ‘The Spice Girls’ by the local media. They “didn’t go very far” as Wilson “lost the brake pedal” with three hours remaining.

“The car was really not looked after. My brother was looking at the car [before the race] and said: ‘My God! You are not going to drive this car.’ It was crazy!”

Muller spent three seasons racing the gorgeous but tricky Peugeot 905 Spider [pictured above] its own series, and was 1994 title runner-up, She saw out her driving days in the Ferrari Challenge, winning her last ever race, despite being two months pregnant with son Yann.

Having run their family F3 team, Muller got more involved in team and driver management, looking after her brother’s career as well as touring car outfit Exagon. Combining that with racing herself became too much. “You can’t be team manager, cooking, organising the logistics and driving. It’s just too much,” she laughs.

For Muller, family clearly comes first. Watching her son Yann race is far more stressful than watching Yvan or racing herself, she says.

“Once you have a kid, it’s just a nightmare. It’s very difficult to be a mother. We did everything with my husband [ex-professional footballer, Yves Ehrlacher] that he [Yann] is not going to race. But at 16 years old he started to race and seven years after he was twice world champion.”

“I did one race with my son, an ice race. He was starting two rows in front of me but I didn’t look at what I was doing. I was looking [at] what he was doing. I understood very quickly that I have to go back and just leave Yvan to deal with the racing. [As a] mum, the first thing you want to tell him is be careful, which is not possible. One day he said to me, ‘mum, you were very stressed on the starting grid’. Since that day, I don’t go anymore on the starting grid or in the pits. No way. I go in the tribune [grandstand], and I hide myself, so I’m sure he doesn’t see me!”

Photo: Cyan Racing

Muller has stayed closely involved with the sport, initially acting as a talent scout for the FIA’s Women in Motorsport [WiM] Commission for 12 years under its president, rally legend Michele Mouton. “We decided to stop at the same time as Jean Todt, to leave new blood doing the job.”

She is now proudly involved in the Iron Dames project, under the “absolutely incredible” Deborah Mayer. “She looks very much after the young kids, she treats her drivers in the best way. What motivates her is her passion. All the team, all the people who work for her, we are all passionate so it is really a pleasure to work for them.”

As part of the Iron Dames “detection cell” she is scouting for talented youngsters. The role also requires a maternal touch.

“[It’s] because they are so young. My job is that they still take as much pleasure as possible first of all and to take away the pressure. I try [to make sure] that the pressure stays only in the tyres.”

Her current focus is on the youngest members of the programme, still in junior karting. “This year we selected two young girls, 12 years old – Vicki Farfus, daughter of works BMW driver Augusto, and a French girl, Mia Oger. Deborah wants to look to the future, for the Iron Dames, so now we start with the young [ones].”

In her FIA role, Muller was part of the team behind the WiM Commission’s Ferrari Driver Academy-affiliated Girls on Track Rising Stars programme. Its graduates have included Ferrari and Mercedes-AMG F1 juniors Maya Weug and Doriane Pin.

While Weug emerged victorious, Muller “was quite sorry for Doriane, because we all saw her potential”.

“I said to Michele ‘we need to do something for her, we can’t leave her’. She didn’t have any budget and her career could have stopped there, you know? So we asked Deborah ‘would you be able to make a test?’. A few days after Doriane did the test in Mugello. And that’s how it started for her.”

Photo: Dutch Photo Agency

“[Iron Dames] managed her very well, but Doriane is so strong. She’s a hard worker. She never gives up. She’s all the time with the data, the engineer and working, working. She trains a lot physically. Now you can see the result. She’s really a nice person, very humble, very normal.”

“I think she’s going to go very far and if there is one [female] driver today able to go to F1, I would bet on her. It’s too early to say F1, but she has the potential, and for sure she will do very high level racing in her career.”

Like Ellen Lohr, Muller has mixed feelings about the merits of the all-female Formula 4 series F1 Academy.

“I’m not the best fan of a women’s championship. Racing generally must be mixed,” she argues. “That’s how the drivers will progress the most. But I must say the way Susie [Wolff] is handling the F1 Academy is very good because on the other side when I see what I have had in my career, I had no advantage. I didn’t want any advantage, but I had more negatives than advantages, because women were not accepted at that time. It means that the one who is going to win is going to go straight up, is not staying for two years or three years in the F1 Academy. It must not be a show like we had already in the past. The level of the F1 Academy is much higher but it must be a bridge to go higher and to drive with boys, with girls, totally mixed.

“I hope we are doing everything to work in the right direction. But for sure, girls like Ellen or me or some other girls, we would have been able to go to F1 at that time. But there was no place really for [women] there.”