Photos: Dan Partel

Dan Partel’s name may be unknown to modern audiences. But junior single-seaters has a lot to thank him for

From Formula 1 support billing and the use of a single-spec chassis and engine to in-house TV coverage and a new level of professionalism, both on and off-track, arguably nobody did more than him to create the blueprint that we are now so familiar with in junior single-seaters.

Over two decades from 1979 to 1999, Partel, an American marketing executive based in Europe, revolutionised the way junior series were organised, financed and above all promoted, in the process launching the careers of a host of famous names including Ayrton Senna, Mika Hakkinen, Michael Schumacher, Rubens Barrichello and David Coulthard.

The apotheosis of the approach was the GM Lotus Euroseries, aimed like today’s Formula Regional at racers stepping up from entry-level single-seaters, which staged its inaugural event at Zandvoort 35 years ago today.

Visionary, stubborn, innovative, forthright and anti-establishment, in many ways Partel was to junior series what Bernie Ecclestone was to F1.

He talked to Formula Scout about how he and the European Formula Drivers’ Association (EFDA) organisation he ran developed the blueprint that almost every junior series globally now follows.

Partel got into motorsport in 1972 “when I bought a car and went racing”. He was working for Philip Morris, owners of the Marlboro cigarette brand, and had recently been transferred from Greece to Germany where he had responsibility for the company’s military business, selling cigarettes to US servicemen based in Europe in the middle of the Cold War.

“I kind of took over the organisation from Peter Argetsinger. I had sponsored the Formula Ford series for two years with Miller High Life beer [another Philip Morris brand] and then I had to pull the sponsorship, things kind of died.

McNish, Frentzen and Hakkinen

“So I pitched up in 1976 and created a five-race series and bought a couple of new cars to dress up the grid, and then in 1977 and 1978 I started a series called the Golden Lion Trophy,” he remembers.

In 1979 Partel founded the EFDA and, with backing from Ford, revived the FF1600 Euroseries.

When “a lot of people said ‘we’re graduating to FF2000’”, EFDA added a parallel European series for the two-litre Ford Pinto engine-powered category, which had been launched in Britain in 1975 to provide an accessible stepping stone from FF1600 to Formula 3.

While EFDA’s European FF1600 championship attracted little attention from leading British runners, the FF200 series shot to international prominence in the early 1980s when Tommy Byrne and Ayrton Senna da Silva, as he was then known, took the title in successive seasons.

The two FFord championships went on to run successfully for eight seasons before Ford suddenly withdrew its support.

“I went to Detroit to see Mike Kranefuss, who was the head of Ford Motorsport globally. I had support from Ford from ’79 though ’87 and he cut my budget. Eliminated it,” Partel says.

As if that blow were not damaging enough, more tragic events awaited. “On March 6, 1987 the Townsend Thoresen ferry boat sank off the port of Zeebrugge. I’d already lost the Ford money and now I’d lost my primary sponsor. So, I was left with a championship with no money to finance it and had to make the decision to stop or to man the turbines full speed ahead.”

Salvation came from Ford’s US automotive rivals, General Motors. “I had been seeing GM in 1982,” says Partel. “And in April 1987 I got a call from them as a follow up to those meetings.

Formula Opel/Vauxhall Lotus champions

| Series/Event | Winners |

|---|---|

| GM Lotus Euroseries | 1988 M Hakkinen 1989 P Kox 1990 R Barrichello 1991 P Lamy 1992 G Rees 1993 P Crinelli 1994 M Campos 1995 J Watt 1996 B Leinders 1997 M Battistuzzi 1998 E van der Linde 1999 T Scheckter |

| German FOpel Challenge | 1988 H-H Frentzen ’89 J Muller ’90 M Krumm ’91 M Mankonen ’92 H Schwitalla ’93 J Hauser ’94 R Goral ’95 W Thimmler ’96 P Kaffer ’97 M Battistuzzi ’98 E van der Linde |

| FVauxhall Lotus | 1988 A McNish ’89 G Dunn ’90 V Sospiri ‘91 K Burt ‘92 P Hunnisett ‘93 D Franchitti ’94 O McAuley ‘95 J Kane ‘96 P Dumbreck ’97 L Burti |

| EFDA Nations Cup | 1990 P Lamy/D Castros Santos (Portugal) ’91 Lamy/Castros Santos (Portugal) ’92 M Kroene/J Verstappen (The Netherlands) ‘93 M Albrecht/H Stromberger (Austria) ’94 T Coronel/D Crevels (The Netherlands) ’95 M Giao/A Couto (Portugal) ’96 P Kaffer/N Simon (Germany) ’97 G Montanari/G Anapoli (Italy) 1998 D Malkin/J Sherwood (GB) |

| FVauxhall Junior | 1991 D Franchitti ’92 M O’Connell ’93 R Firman Jr ’94 P Dumbreck ’95 M Hynes ’96 T Mullen ’97 D Bell ’98 A Pizzonia ’99 G Paffett 2000 R Huff |

| FVauxhall Winter Series | 1993 J Watt ’94 J Kane ’95 M Hynes ’96 none declared |

| FVauxhall Junior WS | 1993 J Minshaw ’94 B di Staulo ’95 D Bell ’96 R Lyons ’97 A Pizzonia ’98 G Pyper |

“They said, ‘we have a new engine to launch and we’d like to do it with a single-seater race car’. As well there were a lot of people who’d like to get involved in F1 but it’s very difficult because the GM head of Europe who would put his name on the approval for F1 was then being transferred back to Detroit and couldn’t control the programme that he’d started.”

“So, we launched in August 1987, GM gave the go-ahead to do Formula Opel Lotus. They had acquired Lotus and they wanted to associate the names of Lotus and General Motors, and [its European brands] Opel and Vauxhall.”

Partel’s main innovation for the new category was to mate GM’s engine to a single one-make chassis.

Nowadays almost all junior single-seater formulas use a spec chassis, with a single supplier for engines and tyres. But in the 1980s this was a radical move.

At the time, series from Formula 2 (which had been succeeded by Formula 3000 in 1985) and F3 to Formula Renault and FFord featured heated battles for honours and orders between chassis manufacturers. The risk for drivers on their way up the ladder was clear – buy the wrong car and you are likely to be off the pace, however talented you might be.

Designed to technical regulations drawn up by EFDA’s technical director Howard Mason, construction of an initial batch of 50 chassis was subcontracted to Reynard, coincidentally a company set up by the winner of the very first EFDA FF2000 championship in 1979, Adrian Reynard.

The price of a complete car, comprising chassis, engine, gearbox and a set of wheels and tyres was initially fixed at £16,000 (around £60,000 in today’s money). The full production run of 50 cars was quickly snapped up by eager customers.

While the car itself “was not the greatest race car in the world by any means; it was a little bit soft and the chassis had some flex in it”, GM’s 2.0L, 16-valve Family II engine was powerful and reliable.

Mallory Park, 1988 (Photo: Stephen Bounds)

“The engine was faster down the straight than a F3 car which, of course, had a ton of downforce whereas we didn’t have any,” explained Partel.

“We had the wings generating some downforce but the floor was a flat floor. They had to change F3 because we were quicker on the straight, albeit considerably slower in the turns and that was creating a political problem because F3 was a development class for F1 so they eventually raised the horsepower of F3 which you could easily do by increasing the bore and the air restrictor. I couldn’t slow my cars down any more, so they had to increase the F3s up to 220 horsepower or something, we were 175hp.”

In fact, EFDA had tried to branch out into F3 in 1987 when it ran a five-round F3 Euroseries, filling a void left by the demise of the European F3 championship at the end of 1984.

“The European F3 series [had been] whittled down to 12 cars – primarily French and Italian. [When] they disbanded the series I said, ‘I’ll show you how to run a F3 series,’ so I started in 1987.”

The series ruffled quite a few feathers, “including the British, the French, the FIA, everybody who was involved in F3 except the competitors”. As a result, Partel was, he says, “stopped from ever doing another F3 race”.

“We had big grids, 44 cars at the opening race at the Nurburgring; that’s pretty impressive and the top British teams like West Surrey Racing came. Through the ’87 F3 series I knew all the people involved in European F3 and as soon as I announced [the GM Lotus Euroseries], we drew interest from everywhere.”

“Of course, it was a race to get the cars and engines hooked up to go racing. Quite literally bits and pieces were being transported around to complete the car build, components weren’t ready on time so had to be retrofitted. It was a challenge, but we got up and running and had a great first year.”

The season had been due to kick off at the Belgian Grand Prix in May 1988, but when that event was rescheduled for late August the curtains went up on the new championship at Zandvoort in June instead.

The season had been due to kick off at the Belgian Grand Prix in May 1988, but when that event was rescheduled for late August the curtains went up on the new championship at Zandvoort in June instead.

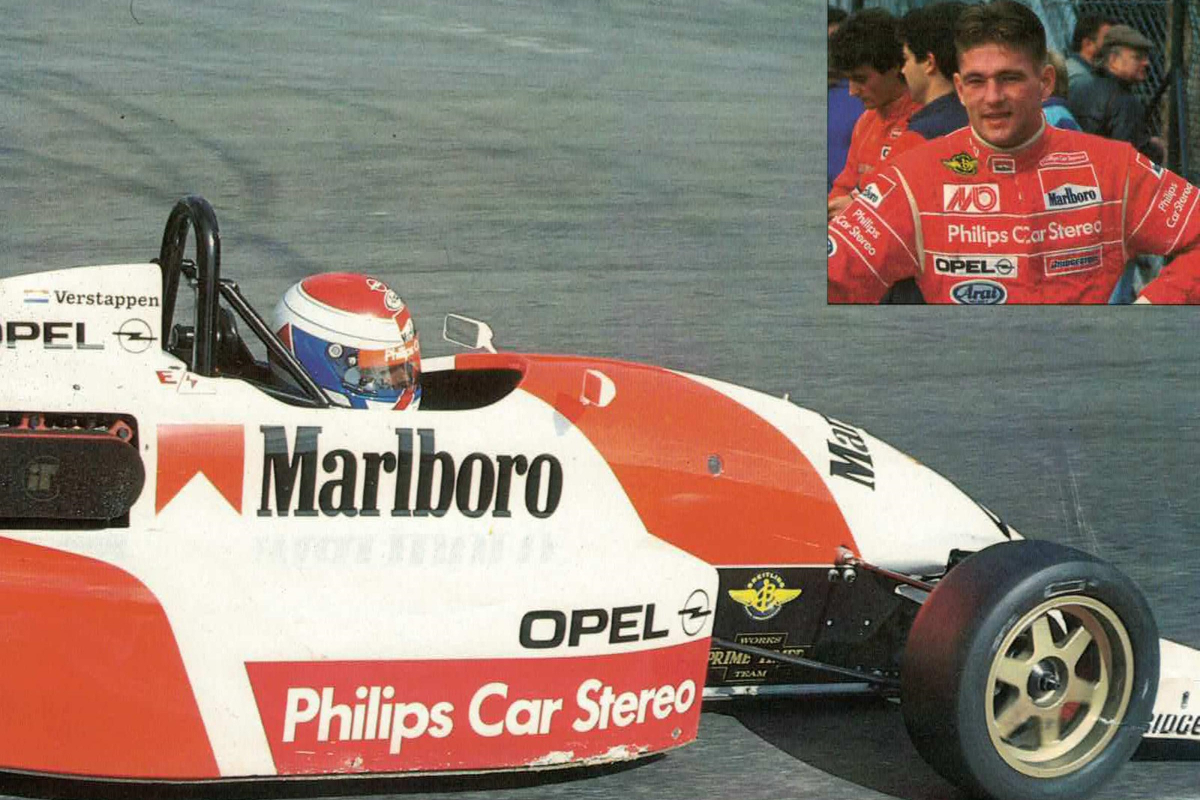

The first season in 1988 was a “huge success” as the Marlboro-backed pair of Mika Hakkinen, who won at Zandvoort, and Alan McNish took the European and British titles respectively for Dragon Motorsport, the Finn pipping Dane Henrik Larsen by a single point.

Partel’s ambitious plan had been to run national series in “at least two of the four primary automobile manufacturing countries, which is Germany, Italy, France and England”, with the continental GM Lotus Euroseries as the flagship.

Getting the national series up-and-running proved harder than anticipated, but Partel was not to be deterred.

“I expected a hard time in France and Italy, which proved correct, but we did launch the German series and the British series.”

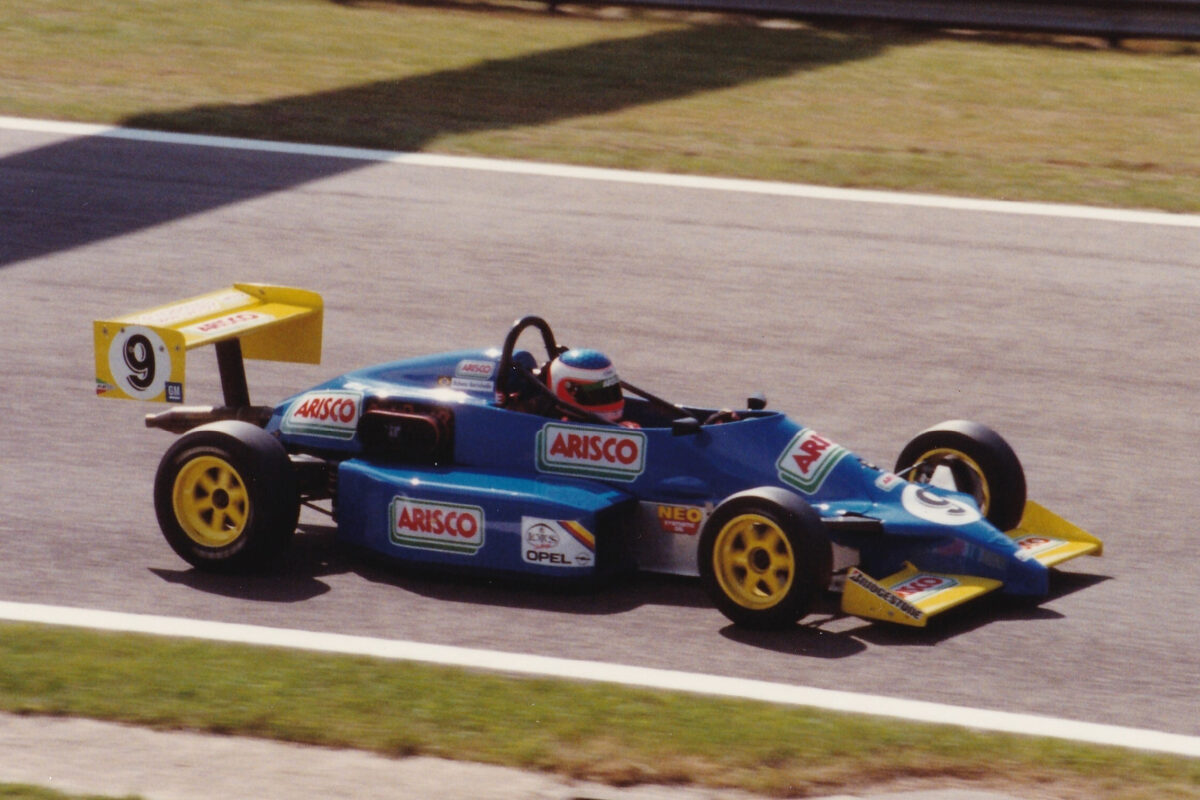

Smaller series were later added in the Benelux region, providing Jos Verstappen his first steps in car racing, as well as Austria, Ireland and Scandinavia.

Junior single-seaters in France had long been the stranglehold of FRenault who, believes Partel, “considered EFDA to be the major threat to its programme”.

“Renault had its territory staked out – so Belgium was kind of like a battleground and England to a much lesser extent. France we never got in there with Opel Lotus although we picked up a couple of French drivers [and] surprisingly enough we picked up several Italian teams.”

Partel’s next masterstroke was in reaching agreement with F1’s impresario, Bernie Ecclestone, to get the Euroseries onto the support programme for a number of grands prix.

Photo: Van Amersfoort Racing

“I said to General Motors that I needed to support F1 grands prix, so they agreed to fund them.” For the championship’s first season in 1988, slots were arranged for five F1 events – France (“which really ticked off the Renault people”), Britain, Germany, Portugal and Spain.

In fact, the championship proved so attractive that by 1990 a qualifying race had to be organised at Zolder to get the numbers within the paddock capacity set by Ecclestone. “We were so oversubscribed – we had 46 entries and I could only take 36 to a grand prix,” explains Partel.

By the third season in 1991, EFDA had added support races at the San Marino, Hungarian and Belgian grands prix, meaning the series was running at all of F1’s European races except Monaco and Italy.

“All the money went through EFDA directly to Allsport Management which was Bernie’s company,” he explains. “About $125,000 a race we paid to F1. For years it was only us and the Porsche Cup – that was the whole support programme for eight grands prix.”

It is now commonplace for the higher junior categories such as F2 and F3 to run exclusively as F1 supports, with other series keen to get onto the schedule where space and budgets permit. Back in the 1980s it was not uncommon for a grand prix to have no support races at all. Once again, the GM Lotus Euroseries was blazing a trail that others would follow in the future.

The next challenge was to ensure television coverage for the new championship. We are now accustomed to live coverage, by TV or online, for every junior category imaginable, usually including qualifying and even free practice.

In the pre-internet days, TV coverage was limited to the odd F2 or F3 race. Partel, however, realised the value to teams and sponsors of the races being viewable for those not at the track.

Recognise these youthful faces?

“So we televised everything. We didn’t have any deep budgets but I had enough production budget for three cameras and then I would work with local TV people and we would trade footage but we began to get a pretty broad coverage of our series.

“The TV stations would get three to five minutes, composite and they liked that. It was free and it gave tremendous exposure to the series but it also gave the teams something to sell to their sponsors, so they did that. We had spectator numbers and good television distribution and a good reputation, so the money started to flow in on the sponsorship side.”

For 1990, Partel hit upon yet another innovation, an event for national teams, a precursor of A1GP 15 years later or today’s FIA Motorsport Games.

Partel’s original plan had been to stage the event at Brands Hatch alongside the long-running FFord Festival in October.

“I went to Brands Hatch to discuss with John Webb [then CEO of the British circuit] but he and I had a falling out. He took the idea of the Nations Cup [for the Festival], which was bullshit in my opinion, because if you have 20 British drivers and you have two Brazilians who’s going to win the nations cup? So, it wasn’t very sophisticated the way they set up their rules and regulations. I was pretty disgusted.”

So Partel and the EFDA went their own way, staging the EFDA Nations Cup for the first time at Spa-Francorchamps in July 1990 with 17 two-car teams, each racing in the national colours of their respective countries.

Importantly, the finishing positions of both drivers would count, with the ‘lowest-scoring’ team taking victory in terms of combined position, and over two heats.

“It put a real challenge to the drivers to figure out how to race as a team. If they’re on a fast track do they qualify and slipstream each other? There were a lot of different strategies that could be generated.”

Pedro Lamy (Photo: Roger Gascoigne)

“Because it was a two-car team virtually they were all no-name drivers, but it was a national team. I promoted that very heavily and televised it in a lot of countries around the world.”

The maiden event went to Portugal, courtesy of future Le Mans Series champion Pedro Lamy and Diogo Castro Santos, followed by Brazilian pair Rubens Barrichello and Andre Ribeiro who both went on to win at single-seaters’ top level.

As Partel notes, many teams were forced to bring in unknown drivers to complete their line-ups and that first event featured an East German national team compete for possibly the first and last time in international motorsport, while future Indy 500 winner Gil de Ferran raced for France, the country of his birth, rather than Brazil.

As Partel openly admits: “I played on the nationalism to improve the audience interest. It worked quite well, and we did nine Nations Cup races, one a year at the end of the season.”

The final year of the Euroseries and the Nations Cup was 1999 but the writing had been on the wall for a few years as GM reduced their funding before ultimately pulling out completely, meaning that “it was kind of downhill for 1997, ’98 and ’99”.

“The problem was that the Opel overhead camshaft 16-valve engine was now out of production for the road cars and so there was no incentive for GM to support the formula if the engines weren’t being used in a production car.”

Speaking at the time, Partel made clear that EFDA had no interest in running “a one-make championship that is not properly financed and supported by a major manufacturer; we won’t run some half-baked concept, and we’ve made our position clear [to the teams]”.

In fact, Partel had invested significant time lining up “a new car designed by Tatuus, which became the car for FR2.0 after I pulled the plug; [I knew] it was going to be a good car”.

Barrichello (Photo: Roger Gascoigne)

The FRenault Eurocup gladly stepped into the vacuum left by the demise of the GM-funded category, dominating the sub-F3 space until the FIA’s wholesale reshaping of the pyramid up to F1 included the introduction of Formula Regional in 2019.

In many ways, Partel’s approach mirrored that of Ecclestone in F1 and both had a vivid understanding of the need for professionalism and entertainment – to put on a show.

“The moment you sell a ticket you’re in showbusiness,” he says. “And showbusiness means you gotta look and act the part. And if you want to attract the best young talent you gotta look professional in all respects.”

His relationship with Ecclestone himself got off to a rocky start but developed into one of mutual respect.

“I first met Ecclestone in ’79 at Zandvoort. It was the first time that we would get invited to do a support race. It was a bit funny, actually,” he recalls.

All the drivers were “lined up to go on the track in the hot sun sitting in the cars”, but for some unknown reason were being prevented from leaving the paddock.

“I was a bit pissed off because I don’t like to see drivers sitting around and then go out and expect to perform. So, I went down to the paddock area and ran into Ecclestone, and I really was a bit of an asshole, to be honest, naïve. We had quite a yelling and screaming match, laced with a lot of profanity, but I think Bernie recognised that I wasn’t somebody who would kowtow to anybody and so we struck a relationship right then.”

Over time, the professional turn-out of the Euroseries paddock became well-known “and Bernie knew all of that and he liked that kind of stuff”.

Ecclestone and Partel

Turning the setting that is the junior single-seater paddock from the ramshackle free-for-all of the 1970s and early 1980s into something resembling today’s meticulously arranged facility was not the work of a moment.

Partel understood the importance of presentation. “People can see a race car but all they see is the outside skin of the body. They don’t see anything underneath the cover. They had to start to look good to give a favourable impression.

“Of course, when you start to get Marlboro and Camel cars thrown in and all these different sponsors it dresses up the paddock and the grid.”

As an indication of the lengths he went to, Partel recounts the tale of the teams’ transporters. “Three or four teams had articulated transporters, other teams had whatever and I had to try and make the paddock look good, so that led to backing the transporters up, it didn’t matter how long they were, they all had to be in line at the back of the truck.”

However, he still had the problem of the varying heights of the transporters. The solution was ingenious but simple – “I put a rule in that you had to have four flags on your truck, one on each corner and the top of the flag pole had to be 10 feet above the ground so some people had longer flagpoles than others but you got a straight line across the top of all these flags.

“When you walked into our paddock you saw the backs of the trucks and the cars under the tents. It all looked neat and clean, but it was also a lot easier to work in the paddock if you have areas for the cars to enter and exit. You can only do that if you’re well-organised, as you only have a limited amount of space.”

The Porsche Supercup, F1’s other regular support act, “had better equipment than we did as far as transporters [but] they eventually followed and that became the support paddocks at all of these grands prix. It was pretty attractive to walk into the paddock and see the teams and the flags were up there and so on.”

The truck alignment (Photo: Dan Partel)

The teams were soon “starting to prosper and make money and they would then put that back into their equipment and so, by the end, the paddocks were a lot easier to do because everybody had articulated transporters, everybody made the effort to make the show look good, the cars’ presentation, the drivers’ overalls, the mechanics and crews so we looked far more professional than we actually were.”

Any spec racing series demands robust technical oversight to ensure a level playing field.

The appointment of Mason, “one of those guys from Farnborough [the Royal Aircraft Establishment facility in England which also produced the likes of March founder Robin Herd] whose hobby was motor racing”, as a dedicated technical scrutineer to keep teams within the rules was, says Partel, “critical”.

Mason had originally been “sent by the RAC to clean up FFord because there was a lot of cheating, and he stayed with EFDA to the end as our technical director”.

“Once you put in a technical scrutineer responsible for the formula rather than responsible for every car racing that day at the general pool, then you can police you formula a lot better, lay the laws down and people start to understand that in this series if you cheat, the probability is that you’re gonna get caught.”

Nevertheless, there will always be some who try to exploit the rules. “We had some cheaters but they disappeared,” Partel says bluntly. “It was tough to keep managing it with the cars in conformance with the regulations and the drawings. And it was the same with the engines.”

After GM’s environmentally-driven decision to mandate the use of catalytic converters “everybody cracked the exhaust system [to get] a big immediate boost to power, so we had to put the rule in that if you have a cracked exhaust system you’re disqualified. Make sure it doesn’t crack.”

Silverstone, 1990 (Photo: Roger Gascoigne)

To keep costs down, EFDA introduced a strict six-tyre limit per weekend with the freedom to “use the tyres any way you wanted to – three fronts and three rears – but guys would come in with a puncture and say that they needed a seventh tyre”.

Partel’s response would be to say: ‘No, you can’t do it. It’s not allowed. Go back and get one of your other spare tyres.’

“And that kept the cost cap alive,” he says now. “All of a sudden there weren’t so many flat tyres any more either!”

Partel left no doubt that he was not a man to be messed with. “Nobody fooled with me. You take me on and you’re asking for big trouble,” he stresses. “I didn’t make any bones about it. Here’s the rules, guys. If you don’t like it, then go some place else. We’re going to run the series this way and you’re going to co-operate or else.”

Partel was not prepared to stand for any nonsense from the young drivers on track either.

In one F1 support race at Hockenheim, he recalls instructing the drivers to be “very careful” at the first chicane.

“I said they’ve got to listen here because there’s money at stake and I can’t afford to have a first turn shunt at an F1 grand prix that takes 45 minutes to clear the circuit. Then we’re on our way home without a race. They all have to understand that and I’ll come down hard on them to make sure they do.

“It’s not just them as individuals but it’s the whole group, the whole championship. GM is not spending $125,000 to have a big accident in the first turn.”

With identical cars in each national series as well as the Euroseries, and big enough budgets to cover a 20-race season, Partel wanted to encourage teams and drivers to run dual programmes. But that meant finding a way to get through the labyrinthine process by which calendars were put together back then, and even today.

Barcelona, 1991 (Photo: Roger Gascoigne)

“The scheduling had been a disaster for years, especially when you go international,” he says. “And the FIA didn’t give a damn.”

Each organising club did their own thing with no thought given to any co-ordination, such that “there was maybe three big races on the weekend, and you wanted to do all three of them, but you could only do one”.

“I wanted my 36 cars every time [for the F1-supporting races] and I couldn’t do that in the early stages with a German FOpel race and a Fomula Vauxhall race on in England at the same time so I insisted that the scheduling of the British, the German and all of those series went through EFDA. We had the money so when I did it with the BARC, I said, ‘You can’t race on that weekend because we have a Euroseries race in France that weekend. You give us your list of races that you want to have, and we’ll go through that list together, and I’ll give you a list of the European races where I don’t have a lot of flexibility.’”

Partel’s single-minded approach aggravated some, not least the FIA, which was simultaneously engaged in a war over control of F1 with Ecclestone and FOCA, the Formula One Constructors’ Association.

“Bernie was developing the FOCA and we were developing EFDA. Then somewhere in the early ’80s there was quite a fight between Jean-Marie Balestre [president of FISA, the sporting wing of the FIA at the time] and Ecclestone. It was all over control, central management of F1, with the efforts of the old FIA to cling to its power.

“Things got testy and I was getting punished by the FIA, so I came out publicly and supported Bernie against Balestre which was pretty risky to do because I was under threats myself that if you raced in an EFDA championship which is unregistered you can lose your licence and circuits should not take these races.

“The circuits loved having full grids of well-turned-out cars but were fearful of being unable to stage other events, so argued that: ‘Hey, we just ordered an international permit. If some guy wants to go and add up the points with five or six races, how are we supposed to stop him?’.

“It was a typical catch-22. The FIA could only sanction competitions that had open regulations, in other words, open engines, open chassis. The one-make championships were done by the national sporting authorities but [they] couldn’t sanction any international series beyond their borders. And the FIA can’t sanction you because you’re a one-make formula.

“It was a typical catch-22. The FIA could only sanction competitions that had open regulations, in other words, open engines, open chassis. The one-make championships were done by the national sporting authorities but [they] couldn’t sanction any international series beyond their borders. And the FIA can’t sanction you because you’re a one-make formula.

“So I just skirted around that for 10 years and just did what I wanted to do. A lot of people were upset but I decided they were wrong. I never registered an EFDA series until 1988 when I registered FOpel. Period. I ran illegal,” he admits.

EFDA may have been outlaws, but they were far from being cowboys. “We were well organised. Paid the money when we were supposed to. No hassle. Pick up the phone. Call Luxembourg. Do a deal. We showed up and delivered exactly what we said. A lot of it was done verbally with the old-time race promoters. Of course, you can’t do anything verbally anymore.”

Again, the similarities with the way Ecclestone was running F1 are striking, as will be obvious to anyone who has seen Ecclestone scooping promoters’ cash into a briefcase in the recent biopic ‘Lucky!’.

Across 20 years, EFDA’s FFord and GM Lotus Euroseries left an indelible mark on motorsport. Others may have copied and improved the model, but Partel was the trailblazer.

He, however, is no fan of how junior series have developed, particularly the explosion in costs.

“Mika Hakkinen came from absolutely no money and he got picked up by Marlboro cigarettes. Anthony Reid had no money at all and then he got a chance to win at the British Grand Prix and he won the Euroseries race and that helped propel his whole career.

“There’s a thousand stories like that. Yeah, there’s the wealthy guys that were out there but there was the type who had no money and became champions. They could do it, they could find an affordable way to race, and be competitive. That’s gone today. It’s all about the money. If you don’t have the money, you don’t race. And you end up with clowns in the back of the F1 grid that have money and no talent.”

McNish & Hakkinen (Photo: Stephen Bounds)