Photos: Prema

When F2 drivers earn the chance to race in F1, it’s validation that their driving on the rung below has been impressive. How much does that apply to 2024, a season of statistical quirks and many F1-bound names

Next year there will be a remarkable number of drivers at single-seaters’ top level who spent 2024 racing in Formula 2.

Eventual champion Gabriel Bortoleto secured a Formula 1 seat with Sauber two rounds before the season concluded, at which point the Invicta Racing driver had a 3.5-point lead in a seven-way title fight. There would have been eight contenders had MP Motorsport’s Franco Colapinto not already stepped up to F1 with Williams.

A lowly 15th in the standings then was Prema’s Ollie Bearman, but he had already made his F1 debut with Ferrari in March’s Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, been signed by Haas for 2025 in July and raced for them in September’s Azerbaijan Grand Prix.

His performance in Saudi Arabia, qualifying 11th and finishing seventh as team-mate Charles Leclerc drove to third, really opened eyes in the F1 paddock. Bearman’s F2 rivals hoped it would lead to more attention on their performances, and it can be confidently said that it has based on how many are now F1, Formula E, IndyCar or Super Formula-bound, or have already got there. Oddly it was only Red Bull (a brand with two F1 teams) that appeared ignorant of F2’s exciting talents while the season was taking place, and the messy way it settled its 2025 line-ups has been the biggest story of the winter so far.

Following Bearman’s debut, and before the season ended, here’s a timeline of top-tier opportunities and deals F2 stars landed:

April: Mercedes-AMG conduct private F1 test for its junior Andrea Kimi Antonell at Red Bull Ring, McLaren calls up its FE reserve driver Taylor Barnard for the Monaco E-Prix.

May: Barnard continues to deputise at McLaren, scoring in both Berlin E-Prix races as Paul Aron cameos with Envision Racing. The next day, FE’s rookie test in Berlin features Jak Crawford (Andretti Global), Enzo Fittipaldi (Jaguar) and Dennis Hauger (Porsche) as well as Andretti and Mahindra’s reserve drivers Zane Maloney and Kush Maini.

June: Aston Martin run junior Crawford in private F1 test at Red Bull Ring.

June: Aston Martin run junior Crawford in private F1 test at Red Bull Ring.

July: Red Bull Racing and Williams call up their respective juniors Isack Hadjar and Franco Colapinto for British Grand Prix practice, Alpine poaches Hitech GP boss Oliver Oakes to be its F1 team principal and Haas hands Bearman a 2025 race seat.

August: Maloney, also Sauber’s reserve driver, joins Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing for a private IndyCar test. Barnard’s FE performances earn him a full-time seat at McLaren for the 2024-25 season, and Antonelli and Colapinto dominate the headlines and appear on track at the Italian Grand Prix. Antonelli makes his practice-only debut with Mercedes as the team finally confirms he will race for them in 2025, and Williams promotes Colapinto to a race seat for the remainder of 2024.

September: Maloney, with no F1 opportunities in sight, signs to become a Lola Yamaha Abt driver in FE for 2024-25. After closing in on points leader Isack Hadjar in F2, McLaren junior Bortoleto is rewarded with a private F1 test at the Red Bull Ring and Bearman scores on a stand-in appearance with Haas at the Azerbaijan GP.

October: Antonelli drives for Mercedes again in Mexico City Grand Prix practice.

November: Andretti signs Crawford as its FE reserve driver, succeeding Maloney, as Fittipaldi tests for McLaren in IndyCar. Sauber announces Bortoleto for 2025, Bearman races for Haas again at the Brazilian Grand Prix and Oakes signs his former F2 driver Aron as Alpine’s reserve driver for the next season.

December: Abu Dhabi Grand Prix practice features Williams junior Luke Browning, and Hadjar at Red Bull’s other team RB.

Most vocal of the F2 drivers when Bearman debuted was Aron, both in support but also of what it meant for the rest of the grid’s prospects.

“In some regard he is representing the F2 grid on the F1 grid now. So I think all of us are wishing him the best of luck, but I think all of us are also a bit jealous that he got the chance,” he explained.

“It’s obviously great that Ollie has the chance, but I think it shouldn’t also take the light off of the other guys on the F2 grid.

Photo: Hitech GP

“There’s still a lot of talent here, and it’s always great for somebody to be able to make the step up, but everybody here is trying to do their best. And I think there’s many drivers who are ready for the step up and they’re experienced and if they had the chance they would do a good job. Let’s see how Ollie does, hopefully our words are true and he does a good job and represents us well.”

His words rang true, and Aron ended his rookie F2 campaign third in the standings. A millimetre error with his DRS led to a disqualification and a shot at the championship runner-up spot, but the Estonian was Bortoleto’s closest rival on pace.

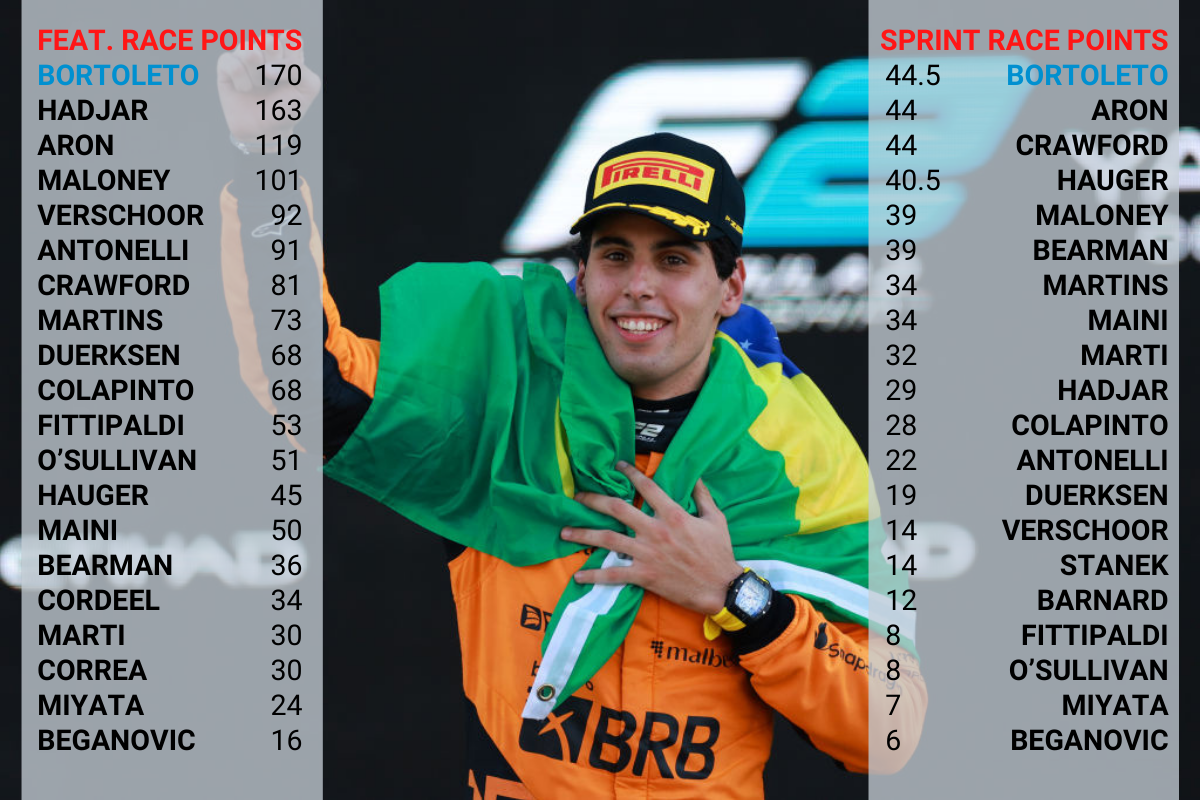

Bortoleto won the title by 22.5 points over F2 sophomore Hadjar, who had gone into the final round just half a point behind and after driving for RB (which will soon be known as Racing Bulls) in F1 post-season testing was chosen to race for the team in 2025. He had a 29-point gap of his own over Aron, and Rodin Motorsport’s Zane Maloney was fourth in the standings despite ending his campaign a round early to start his FE career.

The other drivers who missed races to take up opportunities elsewhere didn’t fare quite as well. Colapinto ended the season ninth, but on a points-per-race basis would have likely beaten DAMS’ Jak Crawford to fifth, particularly considering Formula 3 graduate Oliver Goethe netted 14 points after he took over his car.

Once Hauger set his sights on a future in IndyCar he left F2, dropping him from ninth to 11th in the standings. He had strong one-lap pace, particularly early in the season, but rarely the race pace to match and being absent made no difference to it being the worst of his three years in F2.

Bearman also missed two rounds, and it was persistent engine issues mid-season rather than relaxing at the idea his future was secured, that contributed to his middling pace at several events.

Rolling race pace average

| Pos | Driver | Pace | Pos | Driver | Pace | Pos | Driver | Pace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | Mini | 100.241% | 11 | Marti | 100.848% | 21 | Bearman | 101.098% |

| 1 | Bortoleto | 100.474% | 12 | Bennett | 100.874% | 22 | Correa | 101.139% |

| 2 | Aron | 100.486% | 13 | Duerksen | 100.877% | 23 | Cordeel | 101.237% |

| 3 | Hadjar | 100.568% | 14 | Goethe | 100.881% | 24 | Barnard | 101.242% |

| 4 | Antonelli | 100.623% | 15 | Hauger | 100.967% | 25 | O’Sullivan | 101.305% |

| 5 | Maloney | 100.644% | 16 | Browning | 100.983% | 26 | Villagomez | 101.318% |

| 6 | Beganovic | 100.649% | 17 | Maini | 100.987% | 27 | Esterson | 101.335% |

| 7 | Martins | 100.677% | N/A | Fornaroli | 100.992% | 28 | Stanek | 101.478% |

| 8 | Crawford | 100.750% | 18 | Fittipaldi | 101.007% | 29 | Shields | 102.300% |

| 9 | Mansell | 100.785% | 19 | Colapinto | 101.008% | 30 | Koolen | 102.877% |

| 10 | Verschoor | 100.826% | 20 | Miyata | 101.010% |

Driver did less than three rounds

However he was also nowhere near the front elsewhere; only the 11th fastest on single-lap pace (on average 0.719% off the absoute pace on any given weekend) and 21st on race pace. This is calculated using a rolling average of 10 consecutive laps set at a representative pace, and Bearman’s lack of track limits violations meant there was plenty of usable data to reference.

The fact his three wins came in sprint races reflects his lack of pole-fighting form after his spectacular Saudi Arabian weekend (which included topping F2 qualifying before he got his F1 summoning), and the lack of safety car-led laps in the three races he won should have boosted his race pace average (and it meant only Trident-and-then-MP driver Richard Verschoor spent more laps leading than he did). Prema’s total lack of pace at Bahrain and Barcelona was reflected by the team scoring a singular point at those two circuits, and that achievement went to Antonelli.

He was the better qualifier eight times, Bearman outpaced Antonelli five times, and in Baku the F1-busy Bearman was replaced by FIA F3 Championship runner-up Gabriele Mini. This led to the season’s biggest statistical anomaly, instigated by Mini qualifying eighth in Azerbaijan. This meant he started the reversed-grid sprint race in third, and he held the position to make the podium on his F2 debut (a feat also achieved by Campos Racing’s Pepe Marti in the Bahrain season-opener).

In the feature race he cycled into the lead before pitting, which dropped him to 11th, and he was ninth when he crashed out at turn 15. It caused the shortened race to finish behind the safety car, and the lack of green flag laps meant no drivers had representative race pace data that could be amalgated into their season average, leaving Mini’s sprint race drive his only entry.

It also made him the season’s fastest driver in races on average, having been within 0.241% of AIX Racing’s race winner Joshua Duerksen’s long-run pace, but one data result doesn’t make an average so Bortoleto rightly takes top spot with a late run of podiums that delivered him the title and put him past Aron on race pace. The technical disparity with his DRS may not have been too harmful to Aron’s championship position, but denied him a statistical marker that proved his point about how it’s not just the drivers landing F1 seats that have driven superbly this year.

Absolute pace

| Pos | Driver | Pace | Pos | Driver | Pace | Pos | Driver | Pace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bortoleto | 100.309% | 11 | Bearman | 100.719% | 21 | Cordeel | 101.181% |

| 2 | Aron | 100.320% | N/A | Fornaroli | 100.736% | 22 | Stanek | 101.197% |

| 3 | Hauger | 100.403% | 12 | O’Sullivan | 100.741% | 23 | Browning | 101.235% |

| 4 | Beganovic | 100.429% | 13 | Maini | 100.842% | 24 | Barnard | 101.295% |

| 5 | Hadjar | 100.442% | 14 | Fittipaldi | 100.868% | 25 | Esterson | 101.726% |

| 6 | Antonelli | 100.501% | 15 | Crawford | 100.883% | 26 | Villagomez | 101.764% |

| N/A | Mini | 100.509% | 16 | Duerksen | 100.913% | 27 | Mansell | 101.857% |

| 7 | Colapinto | 100.552% | 17 | Marti | 100.931% | 28 | Bennett | 102.124% |

| 8 | Martins | 100.581% | 18 | Goethe | 100.989% | 29 | Shields | 103.272% |

| 9 | Maloney | 100.637% | 19 | Miyata | 100.999% | 30 | Koolen | 104.077% |

| 10 | Verschoor | 100/652% | 20 | Correa | 101.028% |

Driver did less than three rounds

On single-lap pace it was close between the pair too, with Aron notably claiming pole at Spa-Francorchamps despite a straightline speed disadvantage, and took four poles to Bortoleto’s two. Only the fourth of those was converted into a win, as Aron buckled under pressure when fighting Crawford at Barcelona, got caught out one corner into the race at the Hungaroring and had an even more painful time at Spa where he fought Hadjar until he started to lose pace and then drive, which meant he failed to meet the chequered flag rather than finishing third.

He led more laps this year than Bortoleto, as did six other drivers, but he was far better at scoring points as he finished five feature races in either first or second and finished in the top 10 for all but four of the season’s 28 races.

AIX’s Barnard only scored four times before focusing on FE post-Spa, and therefore missed out on his team’s late surge into competitiveness but did win in Monaco before then. At that point Duerksen had 25 points, seven more than Barnard, and in the remaining eight races he scored a further 62 to leap from 19th to 10th in the standings.

Laps led

1 Verschoor 78 2 Bearman 69 3 Hadjar 60 4 Antonelli 59 =5 Aron & Maloney 55 7 Martins 49 8 Bortoleto 48 9 Marti 40 10 Colapinto 39 11 Maini 32 12 Barnard 30 13 Cordeel 25 14 Correa & Duerksen 24 16 Crawford 18 17 Hauger & O’Sullivan 16 19 Fittipaldi 9 =20 Mansell & Mini 6 22 Goethe 5 23 Villagomez 1